Part:BBa_J23109:Experience

This experience page is provided so that any user may enter their experience using this part.

Please enter

how you used this part and how it worked out.

Applications of BBa_J23109

BBa_K190025 (Planning) constitutive promoter with GVP cluster

BBa_K190031 (Planning) constitutive promoter with fMT

User Reviews

UNIQca12147926714aa0-partinfo-00000000-QINU

|

•••••

ETH Zurich 2014 |

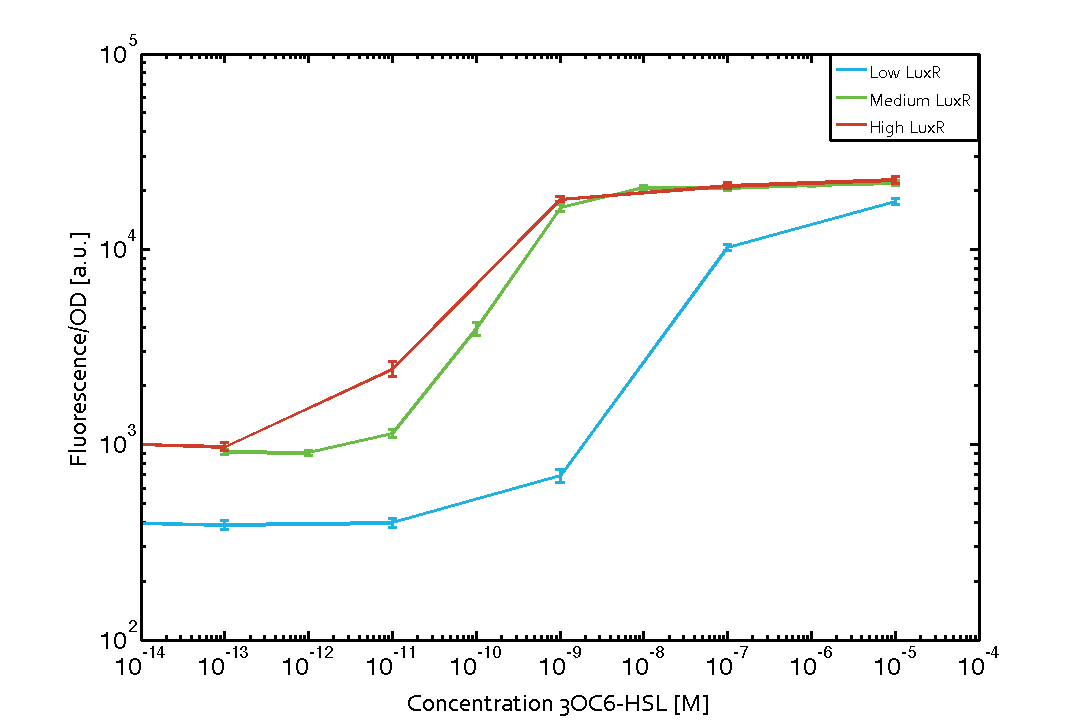

Characterization of the pLux promoter's sensitivity to 3OC6-HSL depending on LuxR under the promoters J23100, J23111, and J23109The amount of regulator LuxR (BBa_C0062) in the system was shown to influence the pLux promoter's response to the inducer concentration (3OC6-HSL). By using the three different constitutive promoters BBa_J23100, BBa_J23109, and BBa_J23111 for the production of LuxR we have measured this effect in terms of fluorescence/OD600 (see Figure 1). Background informationWe used an E. coli TOP10 strain transformed with two medium copy plasmids (about 15 to 20 copies per plasmid and cell). The first plasmid contained the commonly used p15A origin of replication, a kanamycin resistance gene, and promoter pLux (BBa_R0062) followed by RBS (BBa_B0034) and superfolder green fluorescent protein (sfGFP). In general, for spacer and terminator sequences the parts BBa_B0040 and BBa_B0015 were used, respectively. The second plasmid contained the pBR322 origin (pMB1), which yields a stable two-plasmid system together with p15A, an ampicillin resistance gene, and one of three promoters chosen from the Anderson promoter collection followed by luxR (BBa_C0062). The detailed regulator construct design and full sequences (piG0041, piG0046, piG0047) are [http://2014.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/lab/sequences available here]. Experimental Set-UpThe above described E. coli TOP10 strains were grown overnight in Lysogeny Broth (LB) containing kanamycin (50 μg/mL) and ampicillin (200 μg/mL) to an OD600 of about 1.5 (37 °C, 220 rpm). As a reference, a preculture of the same strain lacking the sfGFP gene was included for each assay. The cultures were then diluted 1:40 in fresh LB containing the appropriate antibiotics and measured in triplicates in microtiter plate format on 96-well plates (200 μL culture volume) for 10 h at 37 °C with a Tecan infinite M200 PRO plate reader (optical density measured at 600 nm; fluorescence with an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and an emission wavelength of 530 nm). After 200 min we added the following concentrations of inducers (3OC6-HSL, 3OC12-HSL, and C4-HSL): 10-4 nM and 104 nM (from 100 mM stocks in DMSO). Attention: All the dilutions of 3OC12-HSL should be made in DMSO to avoid precipitation. In addition, in one triplicate only H2O was added as a control. From the the obtained kinetic data, we calculated mean values and plotted the dose-response-curve for 200 min past induction (see Figure 1). ResultsThe measurements of the induced system with 3OC6-HSL concentrations of 10-13 M to 10-5 M showed an increasing sensitivity of the pLux (BBa_R0062) promoter (in terms of fluorescence per OD600) for increasing strength of the promoter controlling LuxR (BBa_C0062) expression (see Figure 1). For BBa_J23100 (strongest promoter chosen) the sensitivity is highest (half maximal effective concentration EC50 approximately 20 pM), for BBa_J23109 (weakest one chosen) the sensitivity is lowest (EC50 approximately 100 pM), with BBa_J23111 (medium) falling between these two but closer to the strong promoter (EC50 approximately 10 nM). Overall, this is in line with the promoter strength given in the Anderson collection.

Figure 1 Influence of varied promoter strength on the expression of LuxR (BBa_C0062) and the resulting effect on pLux (BBa_R0062). The fluorescence per OD600 is shown over an inducer-range of 10-13 M to 10-5 M. The promoters used are: BBa_J23100 (high LuxR expression, red), BBa_J23111 (medium LuxR expression, green), and BBa_J23109 (low LuxR expression, blue). All three promoters are part of the Anderson collection. Data points are mean values of triplicate measurements in 96-well microtiter plates 200 min after induction ± standard deviation. For the full data set and kinetics please [http://2014.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/contact contact] us or visit the [http://2014.igem.org/Team:ETH_Zurich/data/raw raw data] page.

|

Team UT-Tokyo 2014: We sequenced this part in 2014 distribution kit and found that this was not in BioBrick backbone. It has two SpeI restriction sites between prefix and insert sequence.

|

•••••

iGEM-Team Goettingen 2012 |

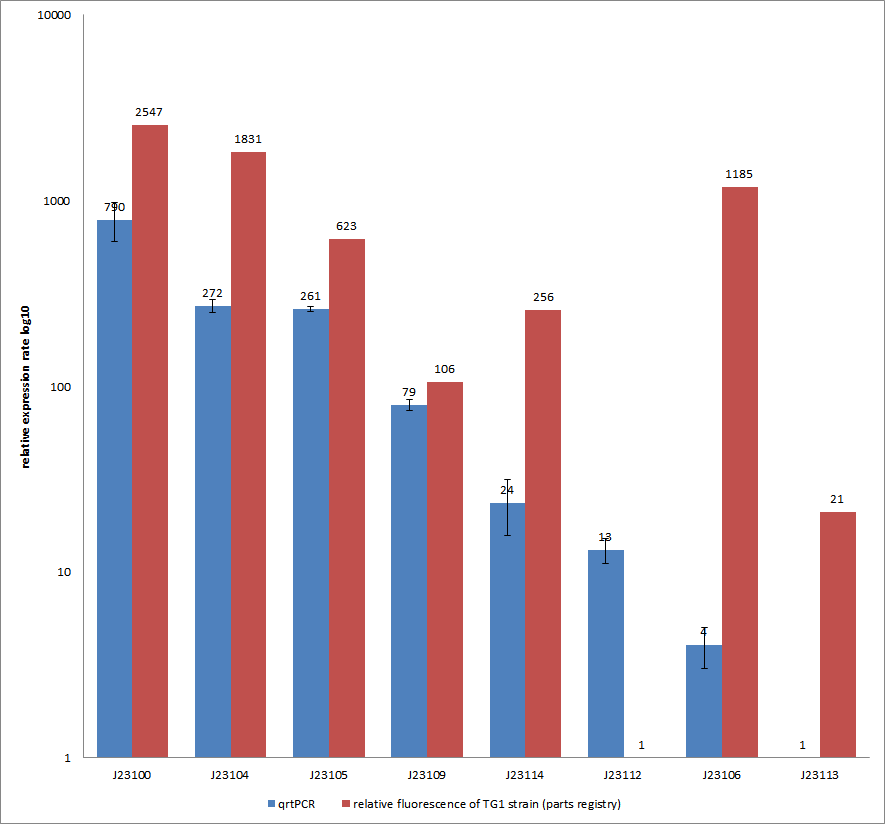

Characterization experiment by qrtPCR on BBa_J23100, BBa_J23104, BBa_J23105, BBa_J23106, BBa_J23109, BBa_J23112, BBa_J23113, BBa_J23114 by iGEM Team Göttingen (by C. Krüger and J. Kampf)DescriptionWe used quantitative real-time PCR as a powerful tool for quantification of gene expression. We used this method to examine the expression rate of the Tar receptor gene under control of promoters from the Anderson family of the parts registry. The BioBricks (K777001-K777008) we used for this experiment can be found here. The reported activities of these promoters are given as the relative fluorescence of these plasmids in strain TG1 [1]. Promoter constructs were cloned into the vector pSB1C3 and expressed in E.coli BL21DE3 grown in LB-media (lysogeny broth). The measurements were performed for each construct and reference as a triplet. Additionally, we included H2O as negative control to predict possible contamination. For the evaluation of our results, the 2–ΔΔCT (Livak) method was applied. We used the weakest promoter with the lowest expression rate as calibrator for the calculations and as reference the housekeeping gene rrsD of E.coli.

You can find detailed information of the qrtPCR approach [http://2012.igem.org/Team:Goettingen/Project/Methods#-.3E_Experimental_design here].

Results & Discussion Comparison of relative expression rates of constitutive promoters by qrtPCR and relative fluorescence (see parts registry,Anderson family). The blue bar indicates the measured expression rates for our constructs (J23100, J23104, J23105, J23106, J23109, J23112, J23113, J23114) and the red ones those for the literature values represented in the “parts registry”. The measurements are illustrated in a logarithmic application. The standard variation was calculated for our measured values (black error bar). As mentioned before, both datasets were collected by methods which produce data at different points after the gene expression. Quantitative real time PCR measures the amount of expressed mRNA while relative fluorescence measurements quantify on protein level. In perspective of stability and half-life periods of mRNA and proteins or due to protein modification, it is comprehensible to obtain varying data-sets and expression rates. Another problem that occurred during our quantitative real-time measurements was the deviation in some of biological replicates. This problem was also observed in another group’s experiments ([http://www.jbioleng.org/content/3/1/4 Kelly et al., 2009]). They mentioned variations across experimental conditions in the absolute activity of the BioBricks. To reduce variation in promoter activity, they measured the activity of promoters relative to BBa_J23101. Furthermore, the iGEM team of Groningen which participated in 2009 also measured the relative fluorescence of TG1 strain with the promoters J23100, J23109 and J23106 via Relative Promoter Units (RPUs). Their values indicated the comparable tendency to our documented values

|

|

•••••

iGEM Groningen 2009 |

We used a number of the constitutive promoter family members for testing our biobricks. The constitutive promoters show the expected level of fluorescence when transformed into E. coli TOP10 cells. Placing parts behind the promoters turned out to be relatively straight forward. We used this part in combination with several biobricks for building our constructs e.g. BBa_I750016 and BBa_K190028 were placed behind the promoters. |

|

•••••

iGEM HKU 2011 |

To start characterizing the promoters, we have performed the red florescence intensity measurements for our selected plasmid in the E.Coli MG1655 strain. The data collected is shown below. It is found that promoter J23106 can lead to a higher expression since the fluorescence intensity per OD600 is the highest, while J23103, J23109, J23116 have relative low expression and fluorescence. As our selected promoters have different strength, thus our team is able to use them to fine tune the protein expression. UNIQca12147926714aa0-partinfo-00000007-QINU

|

1 Registry Star

1 Registry Star