Part:BBa_K525406

Fusion Protein of S-Layer SbpA and mCerulean

Fusion protein of S-layer SgsE and mCerulean.

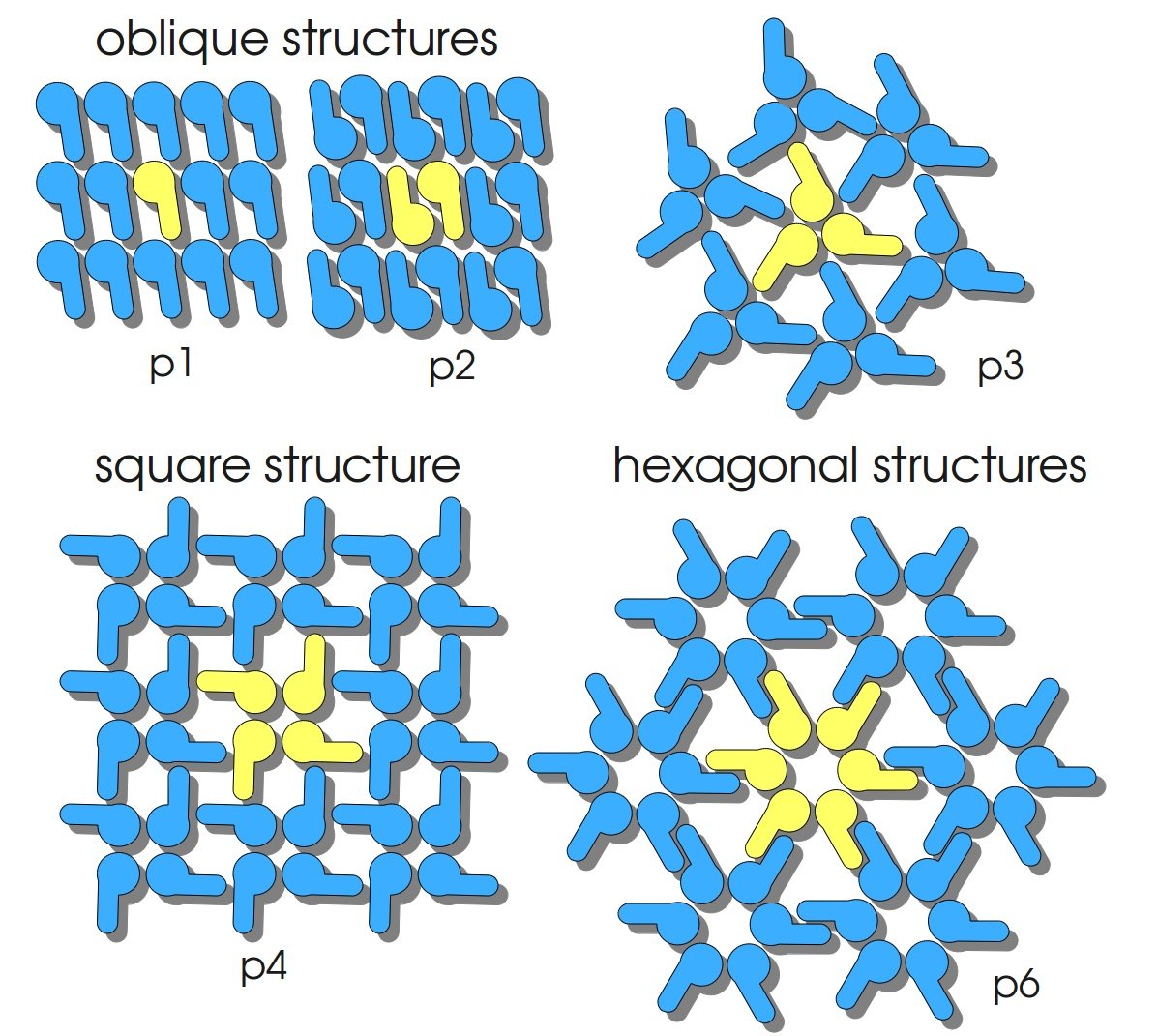

S-layers (crystalline bacterial surface layer) are crystal-like layers consisting of multiple protein monomers and can be found in various (archae-)bacteria. They constitute the outermost part of the cell wall. Especially their ability for self-assembly into distinct geometries is of scientific interest. At phase boundaries, in solutions and on a variety of surfaces they form different lattice structures. The geometry and arrangement is determined by the C-terminal self assembly-domain, which is specific for each S-layer protein. The most common lattice geometries are oblique, square and hexagonal. By modifying the characteristics of the S-layer through combination with functional groups and protein domains as well as their defined position and orientation to eachother (determined by the S-layer geometry) it is possible to realize various practical applications ([http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00573.x/full Sleytr et al., 2007]).

Usage and Biology

S-layer proteins can be used as scaffold for nanobiotechnological applications and devices by e.g. fusing the S-layer's self-assembly domain to other functional protein domains. It is possible to coat surfaces and liposomes with S-layers. A big advantage of S-layers: after expressing in E. coli and purification, the nanobiotechnological system is cell-free. This enhances the biological security of a device.

This fluorescent S-layer fusion protein is used to characterize purification methods and the S-layer's ability to self-assemble on surfaces. It is also possible to use the characteristic of mCerulean as a pH indicator or as FRET donor ([http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/bm901071b Kainz et al., 2010]).

Important parameters

| Experiment | Characteristic | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Expression (E. coli) | Localisation | Inclusion body |

| Compatibility | E. coli KRX and BL21(DE3) | |

| Induction of expression | Expression of T7 polymerase + IPTG, lactose | |

| Specific growth rate (un-/induced) | 0.116 h-1 / 0.092 h-1 | |

| Doubling time (un-/induced) | 5.95 h / 7.51 h | |

| Purification | Molecular weight | 136.9 kDa |

| Theoretical pI | 4.89 | |

| Excitation / emission | 435 / 477 nm | |

| Immobilization behaviour | Immobilization time | 4 h |

Sequence and Features

- 10COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[10]

- 12COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[12]

- 21INCOMPATIBLE WITH RFC[21]Illegal BglII site found at 104

Illegal BglII site found at 221

Illegal XhoI site found at 1996 - 23COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[23]

- 25INCOMPATIBLE WITH RFC[25]Illegal NgoMIV site found at 76

Illegal AgeI site found at 3913 - 1000INCOMPATIBLE WITH RFC[1000]Illegal BsaI.rc site found at 493

Illegal BsaI.rc site found at 622

Expression in E. coli

The SbpA gene under the control of a T7 / lac promoter (BBa_K525403) was fused to mCerulean (BBa_J18930) using Freiburg BioBrick assembly for characterization experiments.

The SbpA|mCerulean fusion protein was overexpressed in E. coli KRX after induction of T7 polymerase by supplementation of 0.1 % L-rhamnose and 1 mM IPTG using the autinduction protocol by Promega.

Methods

Expression of S-layer genes in E. coli

- Chassis: Promega's [http://www.promega.com/products/cloning-and-dna-markers/cloning-tools-and-competent-cells/bacterial-strains-and-competent-cells/single-step-_krx_-competent-cells/ E. coli KRX]

- Medium: LB medium supplemented with 20 mg L-1 chloramphenicol

- For autoinduction: Cultivations in LB-medium were supplemented with 0.1 % L-rhamnose and 1 mM IPTG as inducer and 0.05 % glucose

Measuring of mCerulean

- Take at least 500 µL sample for each measurement (200 µL is needed for one measurement) so you can perform a repeat determination

- Freeze biological samples at -80 °C for storage, keep cell-free at 4 °C in the dark

- To measure the samples thaw at room temperature and fill 200 µL of each sample in one well of a black, flat bottom 96 well microtiter plate (perform at least a repeat determination)

- Measure the fluorescence in a platereader (we used a [http://www.tecan.com/platform/apps/product/index.asp?MenuID=1812&ID=1916&Menu=1&Item=21.2.10.1 Tecan Infinite® M200 platereader]) with following settings:

- 20 sec orbital shaking (1 mm amplitude with a frequency of 87.6 rpm)

- Measurement mode: Top

- Excitation: 433 nm

- Emission: 475 nm

- Number of reads: 25

- Manual gain: 100

- Integration time: 20 µs

Functional Parameters: Austin_UTexas

Burden Imposed by this Part:

Burden is the percent reduction in the growth rate of E. coli cells transformed with a plasmid containing this BioBrick (± values are 95% confidence limits). This BioBrick did not exhibit a burden that was significantly greater than zero (i.e., it appears to have little to no impact on growth). Therefore, users can depend on this part to remain stable for many bacterial cell divisions and in large culture volumes. Refer to any one of the BBa_K3174002 - BBa_K3174007 pages for more information on the methods, an explanation of the sources of burden, and other conclusions from a large-scale measurement project conducted by the 2019 Austin_UTexas team.

This functional parameter was added by the 2020 Austin_UTexas team.

References

Kainz B, Steiner K, Möller M, Pum D, Schäffer C, Sleytr UB, Toca-Herrera JL (2010) Absorption, Steady-State Fluorescence, Fluorescence Lifetime, and 2D Self-Assembly Properties of Engineered Fluorescent S-Layer Fusion Proteins of Geobacillus stearothermophilus NRS 2004/3a, [http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/bm901071b Biomacromolecules 11(1):207-214].

Sleytr UB, Huber C, Ilk N, Pum D, Schuster B, Egelseer EM (2007) S-layers as a tool kit for nanobiotechnological applications, [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00573.x/full FEMS Microbiol Lett 267(2):131-144].

//function/reporter/fluorescence

//proteindomain/internal

| color | Blue |