Part:BBa_K1847008

lldRO1-J23117-lldRO2

Collection of promoters regulated by LldR.

Sequence and Features

- 10COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[10]

- 12INCOMPATIBLE WITH RFC[12]Illegal NheI site found at 78

Illegal NheI site found at 101 - 21COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[21]

- 23COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[23]

- 25COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[25]

- 1000COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[1000]

Usage and Biology

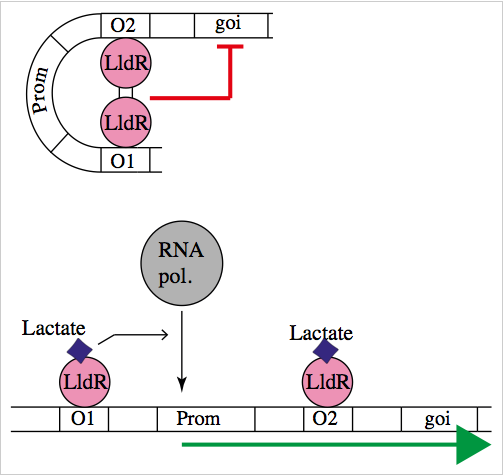

The natural promoter of LldR (Part:BBa_K822000) consists of two operators (O1 and O2) and a promoter which is intercalated between the operators. It regulates the expression of the lldPRD operon, and it is involved in L-lactate metabolism. This promoter is repressed by a dimer of LldR, possibly by forming a DNA loop that does not allow the RNA polymerase to bind to the promoter. LldR can also have a function as an activator [1]. The repression of the promoter can be removed by lactate.

Characterization of the promoter

We wanted to know how the promoter would respond to the lactate presence and how important is the architecture of the promoter in this response. For this regard, we built several promoters. Part:BBa_K1847002, Part:BBa_K1847003, Part:BBa_K1847004, Part:BBa_K1847005, Part:BBa_K1847006, Part:BBa_K1847007, Part:BBa_K1847008, and Part:BBa_K1847009.

Genetic design for characterization with LldR

To test our promoter we designed a plasmid containing the promoter with sfGFP in a medium copy plasmid pSEVA261 and transformed it into Escherichia coli TOP10. Then, we added a second plasmid containing lldR with a medium strong promoter (Part:BBa_J23118) and a strong RBS (Part:BBa_B0034) in pSEVA371 backbone. According to literature [1], LldR will repress the promoter and by the addition of lactate the production of GFP will start, as the repressor will be removed.

Genetic design for characterization with LldP-LldP

The second step for our characterization was to add an L-lactate permease (LldP), which despite its name is an active transporter of L-lactate, D-lactate and glycolate. To understand the effect of LldP (L-lactatep permease) in our system, we tried the following conditions:

- Medium copy plasmid with the promoter and sfGFP+ J23114-B0032-lldP-lldR (LldP and LldR are under the control of the same weak promoter) in low copy number plasmid

- Medium copy plasmid with the promoter and sfGFP + J23118-B0032-lldP-lldR (LldP and LldR are under the control of the same medium promoter) in low copy number plasmid

Characterization in a different medium

DMEM and RPMI mediums for mammalian cells where used to characterize this promoter. Two conditions were tested:

- Plasmid with the promoter and sfGFP + J23118-B0032-lldR

- Plasmid with the promoter and sfGFP+ J23118-B0034-lldP-lldR

Plate reader

E. coli TOP10 strains were grown overnight in Lysogeny Broth (LB) containing kanamycin (50 µg/mL) and chloramphenicol (12.5 µg/mL) at 37°C and 200 rpm. Cultures were diluted 1:50 in fresh LB with the corresponding antibiotic and transferred to a 96-well plate (200 µL/well). Cultures were grown for 90 min to arrive to exponential phase and then different concentrations of lactate were added. Samples were always made in triplicates and a blank of LB with the corresponding lactate concentration was done. During 7 h the absorbance at OD600 and fluorescence (excitation 488 nm and emission 530 nm) were measured with intervals of 7 min. The plate was always kept at 37°C in a Tecan Infinite M200 Pro Plate Reader. We calculated dose-response curves from the exponential phase of the bacteria after normalizing fluorescence by optical density.

Modeling

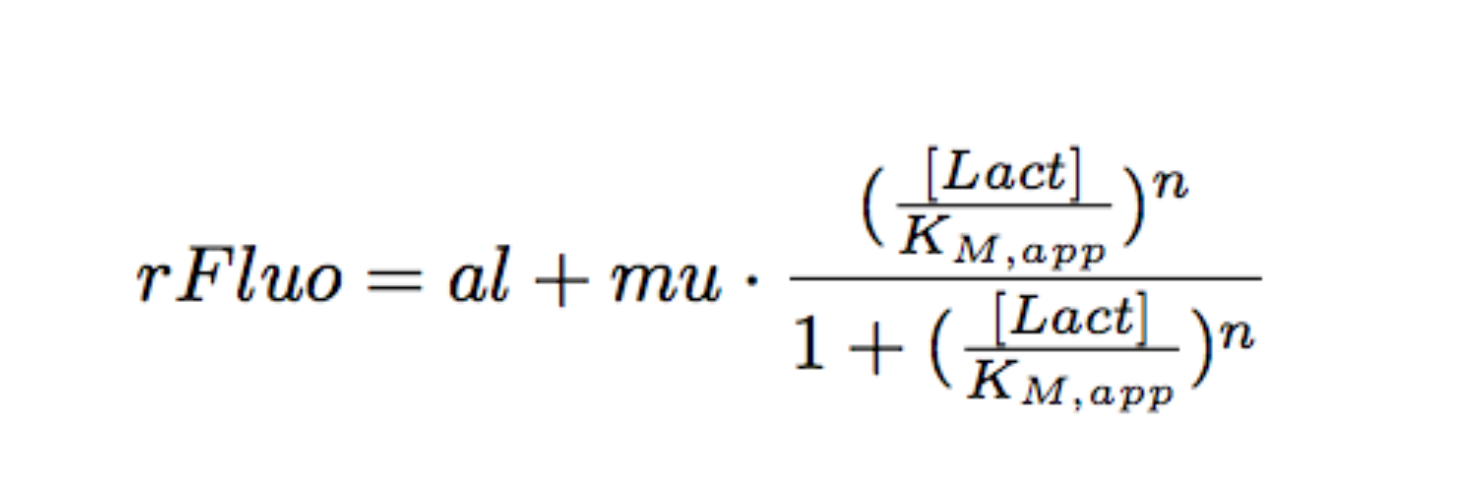

Each experimental data set was fitted to a Hill function using the Least Absolute Residual method (Fitting Toolbox in MatLab).

Where:

- al: leakiness in µM/min

- mu: constant in µM/min

- KM: half-maximum effective concentration (a representation of sensitivity) in µM

- n: Hill coefficient (a representation of cooperativity), unitless

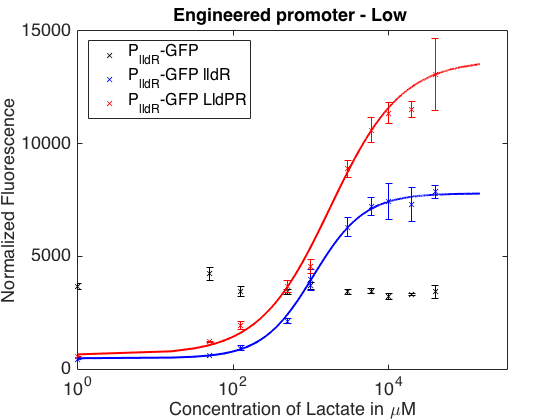

| J23118-B0034-lldR | J23118-B0034-lldP-lldR | J23114-B0032-lldP-lldR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient values | KM=1075 (889.5, 1261) | KM=1751 (918.5, 2584) | KM=337.7 (152.4, 522.9) |

| al = 479.3 (-142.2, 1101) | al = 550 (-1635, 2735) | al = 3444 (2571, 4317) | |

| mu = 7311 (6583, 8039) | mu = 1.318e+04 (1.03e+04, 1.607e+04) | mu = 4886 (3817, 5954) | |

| n1 = 1.326 (1.063, 1.588) | n1 = 0.9388 (0.5614, 1.316) | n1 = 1.09 (0.531, 1.649) | |

| Goodness to fit | sse: 4.2545e+07 | sse: 6.4285e+08 | sse: 2.7027e+08 |

| rsquare: 0.9964 | rsquare: 0.9879 | rsquare: 0.9743 | |

| fe: 7 | dfe: 7 | dfe: 7 | |

| adjrsquare: 0.9949 | adjrsquare: 0.9828 | adjrsquare: 0.9633 | |

| rmse: 2.4653e+03 | rmse: 9.5831e+03 | rmse: 6.2137e+03 |

As can be seen in the picture above, when PlldR GFP is alone, the fluorescence levels do not vary with lactate concentration. However, if PlldR GFP is expressed in a system with constitutive expression of LldR, at low concentrations of lactate there is repression of the promoter, while at high concentrations there is activation. Activation is higher when there is constitutive expression of LldP-LldR. KM is shifted regarding the wild-type promoter, which makes this promoter more sensitive.

The promoter has higher ON/OFF ratios than the wild-type promoter (see Table 1). Its KM is higher than the one from the wild-type promoter, meaning that is has lower affinity for the substrate.

This promoter is one from our designed and tested synthetic promoters based on the wild-type PlldR. In the following table, one can see the ON/OFF ratios and the KM of the wild-type promoter and the three more prominent members of the library.

Table 1: ON/OFF ratio

| LldR | Additional LldP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| J23118-B0034-lldR | J23118-B0034-lldP-lldR | J23114-B0032-lldP-lldR | ||

| Part:BBa_K822000 (wild-type) | 10.35 | 8.04 | 1.16 | |

| Part:BBa_K1847008 | 15.26 | 23.96 | 1.42 | Increasing promoter strength |

| Part:BBa_K1847009 | 2.5 | 24.34 | 0.96 | |

| Part:BBa_K1847007 | 2.15 | 3.85 | 1.29 | |

Table 2: KM (µM)

| J23118-B0034-lldR | J23118-B0034-lldP-lldR | J23114-B0032-lldP-lldR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Part:BBa_K822000 (wild-type) | 955 | 1930 | 720.2 |

| Part:BBa_K1847008 | 1075 | 1751 | 337.5 |

| Part:BBa_K1847009 | 977.5 | 2361 | 459.8 |

| Part:BBa_K1847007 | 697.7 | 1977 | 1337 |

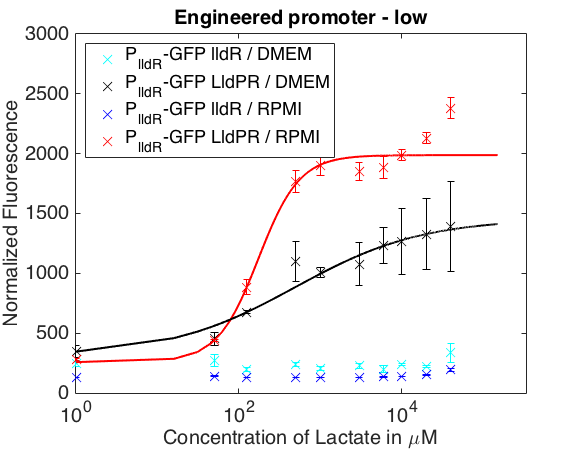

The graph below shows the behavior of our promoter in two mediums usually used for mammalian cell cultures. The promoter does not respond to lactate concentrations in DMEM while in RPMI it shows a behavior similar to the one in LB.

| RPMI | DMEM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| J23118-B0034-lldR | J23118-B0034-lldP-lldR | J23118-B0034-lldR | J23118-B0034-lldP-lldR | |

| Coefficient values | K=3.389e+04 (-1.7e+05, 2.378e+05) | K=173.6 (15.19, 331.9) | K=5e+04 (-2.563e+05, 3.563e+05) | K = 448.4 (52.45, 844.3) |

| al = 136.2 (130.8, 141.7) | al = 253 (-584.6, 1091) | al = 230.3 (202.7, 258) | al = 314.1 (138.6, 489.5) | |

| mu = 92.3 (-659.7, 844.3) | mu = 1735 (863.1, 2607) | mu = 253.2 (-1098, 1605) | mu = 1085 (907.3, 1263) | |

| n1 = 3.165 (-13.87, 20.2) | n1 = 1.7 (0.05844, 3.341) | n1 = 1.5 (fixed at bound) | n1 = 0.7 (fixed at bound) | |

| Goodness to fit | sse: 939.5028 | sse: 1.6713e+07 | sse: 1.8073e+05 | sse: 5.1609e+06 |

| rsquare: 0.9640 | rsquare: 0.8846 | rsquare: 0.7522 | rsquare: 0.9608 | |

| fe: 7 | dfe: 7 | dfe: 8 | dfe: 8 | |

| adjrsquare: 0.9485 | adjrsquare: 0.8351 | adjrsquare: 0.6902 | adjrsquare: 0.9510 | |

| rmse: 11.5851 | rmse: 1.5452e+03 | rmse: 150.3044 | rmse: 803.1891 | |

Characterization and improvement of lactate sensors using lldRO1-J23117-lldRO2 promoter in D-Alanine knock-out auxotrophic bacteria

Group: Team NUS_Singapore 2016

Authors: Keshiniy Madivannan, Janice Darikho and Nguyen Hoang Diem Phuong

Introduction

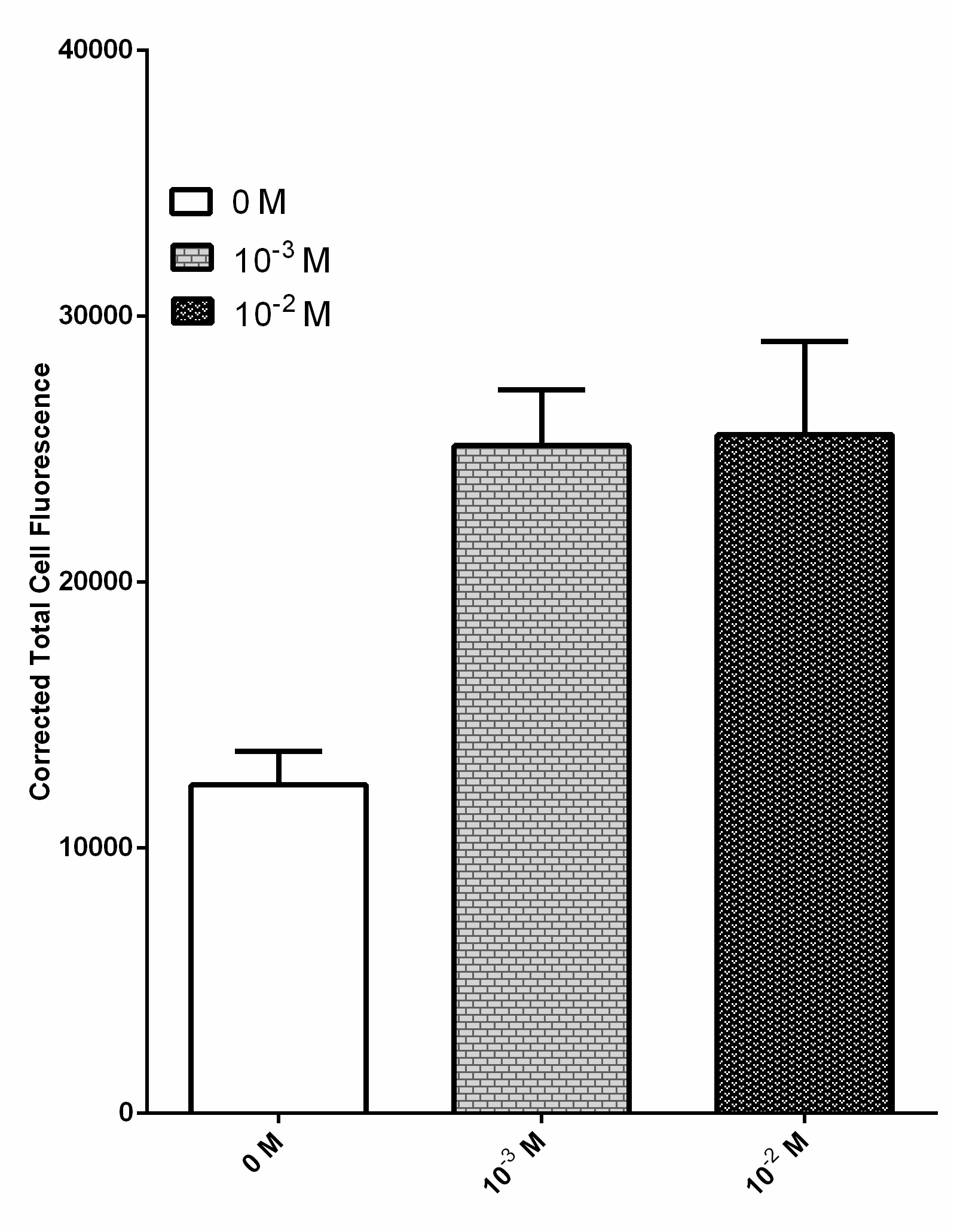

Due to their ability to deregulate normal cellular energetics, cancer cells are found to undergo aerobic glycolysis followed by lactic acid fermentation in the cytosol, resulting in the elevated production and accumulation of L-lactate in the surrounding environment [2][3][4]. The RIOT sensor collection was designed to detect increased level of L-lactate produced by tumor cells in the microenvironment. A lactate-sensitive promoter obtained from 2015 ETH_Zurich team, lldRO1-J23117-lldRO2 (Part:BBa_K1847008) was used as starting material. They characterized this part by ligating it to a strong RBS Part:BBa_B0034 and sfGFP. This combination was quite leaky which resulted in the high expression of the GFP reporter in the absence of lactate (Figure 3).

Overnight culture of bacteria transformed with this sensor was diluted and incubated with various lactate concentration including 0 M, 10-3 M and 10-2 M. Fluorescent images of each condition were processed by ImageJ software to obtain the corrected total cell fluorescence. n = 40 and the error bars stands for SEM

Our new designed lactate sensing plasmid has been engineered to minimise basal expression of reporter gene without lactate. We minimise the basal expression of our reporter by linking different strength RBS parts with lldRO1-J23117-lldRO2 promoter obtained from 2015 ETH_Zurich team (Figure 4). Our engineered sensors have little or no basal expression and significant increase in reporter output (either by GFP or Alanine Racemase, ALR expression) in the presence of lactate. Our strategy allows strict amount of reporter expression, thus increasing sensitivity of lactate detection, and minimise false positive results. ALR is an enzyme responsible for the synthesis of D-alanine, an essential amino acid required for bacterial survival [5]. Transformed bacteria expressing our ideal sensor are expected to survive in small numbers in mild lactate concentration from the microenvironment. Once the bacteria are exposed to the increased lactate concentration in the tumor microenvironment, these bacteria will start to grow rapidly and this will significantly enhance the detection of tumor or delivery of biomolecules into tumor cells.

RIOT sensors 1 (Part:BBa_K1897019) and 7 (Part:BBa_K1897021) contain the lldRO1-J23117-lldRO2 promoter (Part:BBa_K1847008), a coding sequence of Alanine Racemase and a t0 lambda terminator.However, RIOT sensor 1 contains a strong RBS (Part:BBa_B0034) while RIOT sensor 7 contains a weak RBS (Part:BBa_B0033) which has efficiency of about 1% relative to the strong RBS.

Methods

We transformed E. coli Nissle ∆alr, a D-alanine auxotrophic mutant bacteria [6] with our RIOT sensors plasmid which express ALR reporter in the presence of elevated L-lactate. Without the expression of ALR in this knockout bacteria, the bacteria will not survive. However, in the presence of L-lactate, the RIOT sensor is able to express the reporter gene, ALR, thus increasing growth rate of the mutant bacteria. Therefore, the performance of RIOT sensors were assessed by the growth rate of transformed bacteria over a range of lactate concentration in M9 minimal media via natural logarithm (LN) of OD600.

Results

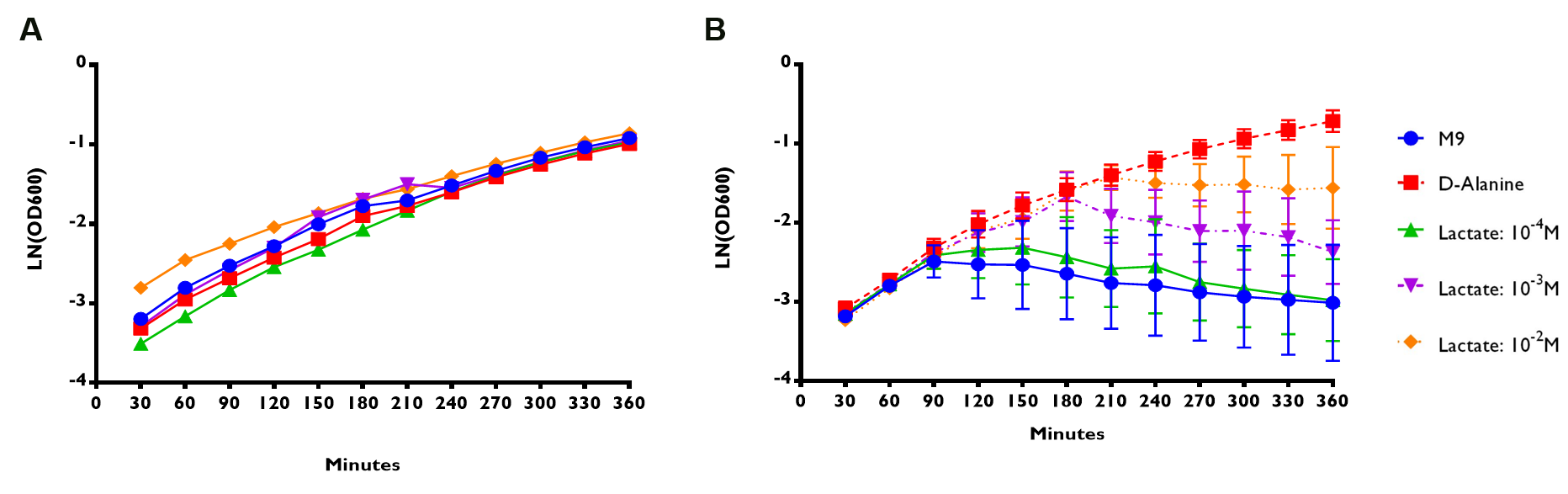

D-alanine knockout auxotrophic mutant bacteria were transformed with plasmids containing ALR gene under the control of RIOT sensor 1 or 7 which are lactate sensitive promoters (Figure 4). The overnight culture were spun down, washed and resuspended with M9 minimal media without D-alanine supplement. Then, samples were subjected to different treatments as shown below (Figure 5).

- M9 without D-alanine supplement

- M9 with 50 µg/ml D-alanine supplement

- M9 with addition of lactate concentration range of 10-4 to 10-2 M.

Figure 5A shows that E. coli Nissle∆alr expressing RIOT sensor 1 were able to grow and survive even without the addition of lactate. The growth rate for the transformed bacteria were similar regardless of the lactate concentration. On the contrary, E. coli Nissle∆alr transformed with RIOT sensor 7 showed different growth rate corresponding to the changes in lactate concentration (Figure 5B).

The growth rate of the mutant bacteria expressing the various RIOT sensor , with or without lactate were measured by taking the absorbance of OD600 nm at various timepoints for a total of 6 hr . We use the natural log of the OD600nm reading to reflect the growth rate of bacteria expressing different RIOT sensor with different lactate concentration.

(A) RIOT sensor 1: p70-34-ALR-Terminator (Part:BBa_K1897019) consists of lldRO1-J23117-lldRO2 promoter ligated to a strong RBS (Part:BBa_B0034) and Alanine Racemase (ALR). N=1

(B) RIOT sensor 7: p70-33-ALR-Terminator (Part:BBa_K1897021) consists of lldRO1-J23117-lldRO2 promoter ligated to a weak RBS (Part:BBa_B0033) and ALR. N=3 and the error bars stand for SEM.

We used linear regression analysis to fit our data of bacterial growth rate using four data points of LN (OD600) values from 90 to 180 min of each sensor. This is because the growth rate of each constructs appeared to deviate from each other at the 90-minute time point (Figure 5).

Table 3: Comparisons of bacteria growth rate between RIOT sensor 1 and 7

RIOT sensor 1: p70-34-ALR-Terminator (Part:BBa_K1897019) consists of lldRO1-J23117-lldRO2 promoter ligated to Alanine Racemase ( N=1 ± SEM).

RIOT sensor 7:p70-33-ALR-Terminator (Part:BBa_K1897021) consists of lldRO1-J23117-lldRO2 promoter ligated to a weak RBS (Part:BBa_B0033) and ALR (N=3 ± SEM).

Doubling time – LN (2) / Growth rate

| RIOT sensor No. | Lactate concentration (M) | Growth rate (min-1) | Doubling time (min) | R square |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: p70-34-ALR-Terminator | 10-4 | 0.00935 ± 0.000594 | 74.3 ± 4.73 | 0.992 |

| 10-3 | 0.0107 ± 0.000505 | 64.9 ± 3.06 | 0.996 | |

| 10-2 | 0.00659 ± 0.000173 | 105.2 ± 2.76 | 0.999 | |

| 7: p70-33-ALR-Terminator | 10-4 | No growth was observed | ||

| 10-3 | 0.00756 ± 0.000789 | 92.7 ± 9.67 | 0.979 | |

| 10-2 | 0.00880 ± 0.000863 | 79.5 ± 7.80 | 0.981 | |

Discussion and Conclusion

The rate and the level of reporter gene expression of each individual sensor plasmid at each condition was analysed by the growth rate of transformed bacteria using linear regression analysis. The slope of each fitted linear line represents the growth rate of bacteria. Our results shown in Figure 5 suggested that RIOT sensor 1, p70-34-ALR-Terminator (Part:BBa_K1897019) exhibited high leakiness in reporter gene expression, regardless of the lactate concentration tested. Moreover, Table 3 showed that transformed bacteria with sensor 1 under different treatments appeared to have similar initial growth rate compared to those were grown in the media containing D-alanine supplement (0.008 – 0.009 min-1, p-value < 0.01). This is because the amount of ALR expressed at the lowest lactate concentration is likely to be sufficient to convert enough L-alanine into D-alanine, which help the bacteria to survive. The insignificant differences in growth rate of bacteria treated with various lactate concentrations indicated that RIOT sensor using lldRO1-J23117-lldRO2 promoter ligated with strong RBS designed by ETH_Zurich 2015 was not sensitive enough to detect small changes in lactate concentration in the tumour microenvironment.

In contrast, our RIOT sensor 7, p70-33-ALR-Terminator (Part:BBa_K1897021) exhibited very minimal leakiness without the presence of lactate. The transformed bacteria were unable to grow in the absence or at low lactate concentration (10-4 M). Addition of lactate at high concentration (10-3 and 10-2 M) rescued the transformed bacteria grown in media without D-alanine. According to Table 3, the growth rate of bacteria transformed with sensor 7 grown in lactate concentration of 10-4 M was not significantly different from zero. RIOT sensor 7 also showed an increase in growth rate or a decrease in doubling time from 92.7 to 79.5 minutes when lactate concentration increased from 10-3 M to 10-2 M.

In conclusion, we have characterized the output of lldRO1-J23117-lldRO2 (Part:BBa_K1847008 from ETH_Zurich 2015) in a new chassis which was E. coli Nissle ∆alr, a D-alanine auxotrophic mutant bacteria to detect lactate in tumour microenvironment. The characterization result of RIOT sensor 7 shows that we have successfully minimized the leakiness and enhance the sensitivity to lactate of sensor using the lldRO1-J23117-lldRO2 promoter from ETH_Zurich without adding LldP and LldR. Bacteria transformed with sensor 7 are expected to be able to survive in small numbers in mild lactate concentration of the blood and once reaching tumour site, their growth will be increased by the high lactate concentration there, which will enhance the detection signal or the delivery of biomolecules into tumour cells.

References

- J Bacteriol. 2008 Apr; 190(8): 2997–3005.

- Alfarouk, K.O., Verduzco, D., Rauch, C., Muddathir, A.K., Bashir, A.H., Elhassan, G.O., Ibrahim, M.E., Orozco, J.D.P., Cardone, R.A., Reshkin, S.J. and Harguindey, S. (2015). Glycolysis, tumor metabolism, cancer growth and dissemination. A new pH-based etiopathogenic perspective and therapeutic approach to an old cancer question. Oncoscience, 2(4), p.317.

- Chen, Z., Lu, W., Garcia-Prieto, C., & Huang, P. (2007). The Warburg effect and its cancer therapeutic implications. Journal of bioenergetics and biomembranes, 39(3), 267-274.

- Vander Heiden, M. G., Cantley, L. C., & Thompson, C. B. (2009). Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science, 324(5930), 1029-1033.

- Walsh, C. T. (1989). Enzymes in the D-alanine branch of bacterial cell wall peptidoglycan assembly. Journal of biological chemistry, 264(5), 2393-2396.

- In Young Hwang, Elvin Koh, Adison Wong, John C. March, William E. Bentley, Yung Seng Lee and Matthew Wook Chang (2016). Engineered probiotic microbes eliminate and prevent pathogen infection in the mammalian gut. Manuscript submitted.

Characterization of the Lactate inducible promoter in BL21(DE3) with sfGFP as the reporter <h1>

| None |