Difference between revisions of "Part:BBa J10050:Experience"

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

= Characterization of weak promoter (BBa_J23113) and weak RBS (BBa_B0031) = | = Characterization of weak promoter (BBa_J23113) and weak RBS (BBa_B0031) = | ||

| − | + | Differences in promoter strength had more effect on enzymatic expression compared to differences in RBS strengths as evidenced in the graphs below. Lambert_GA 2019 had originally thought that BBa_J10050 would result in the least amount of expression out of the tested combinations, but this part, along with BBa_J10051 and BBa_J10052, all shared the lowest expression out of the combinations. This is due to the translation rate not being an important factor in the determination of expression of ONP; however, the promoter strength is a significant factor. In other words, expression values are significantly different with different promoters but not with different RBS strengths. | |

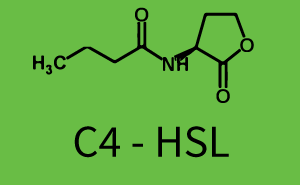

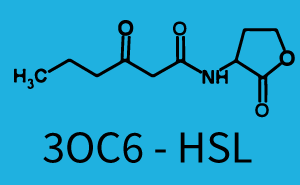

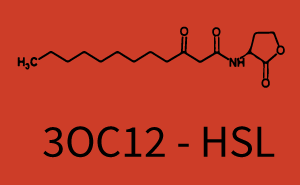

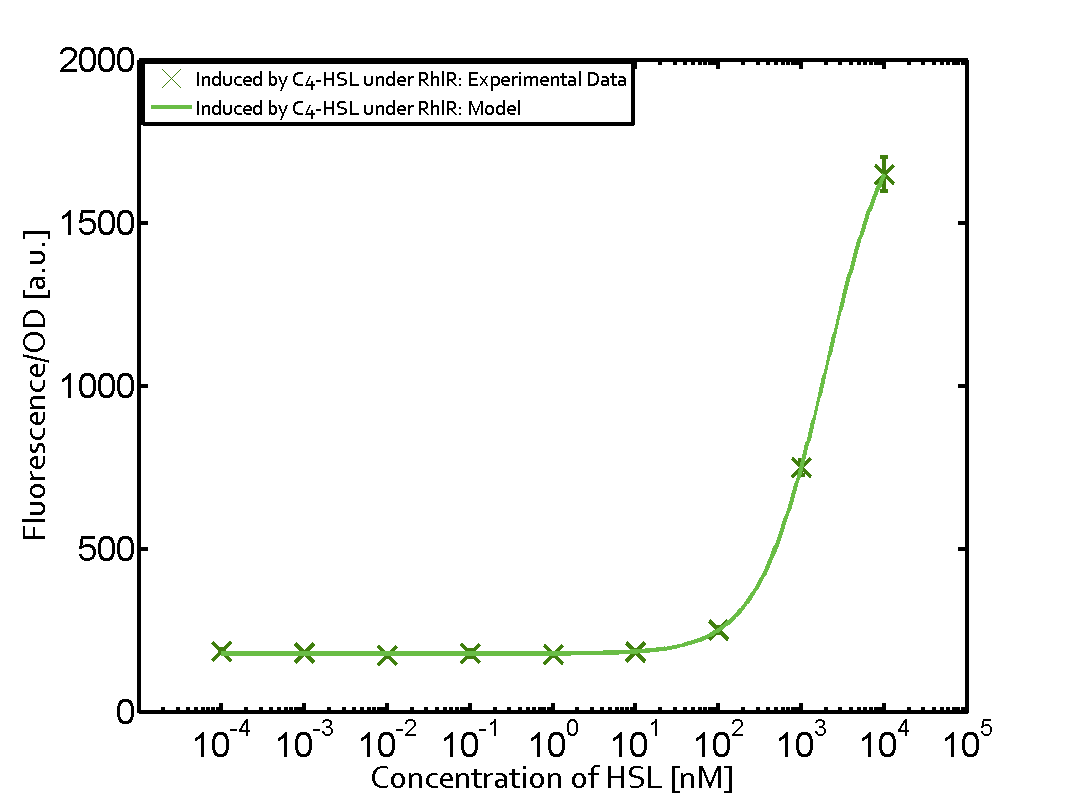

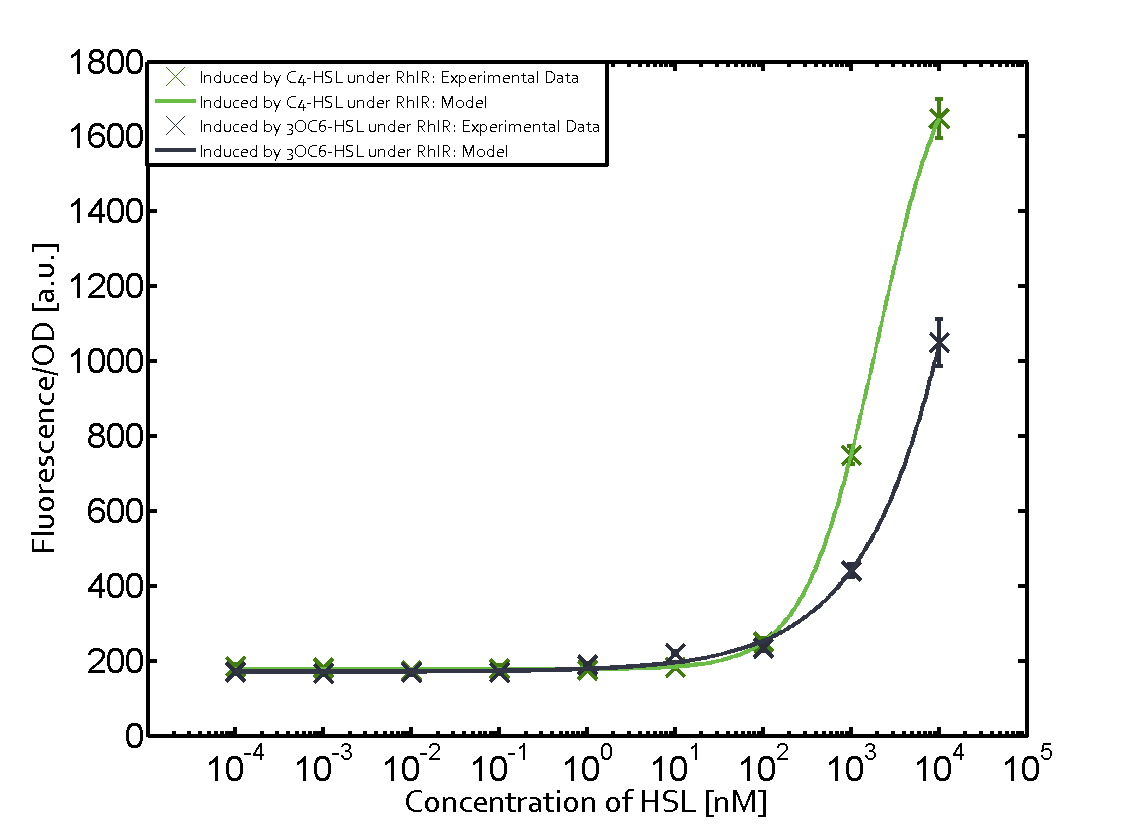

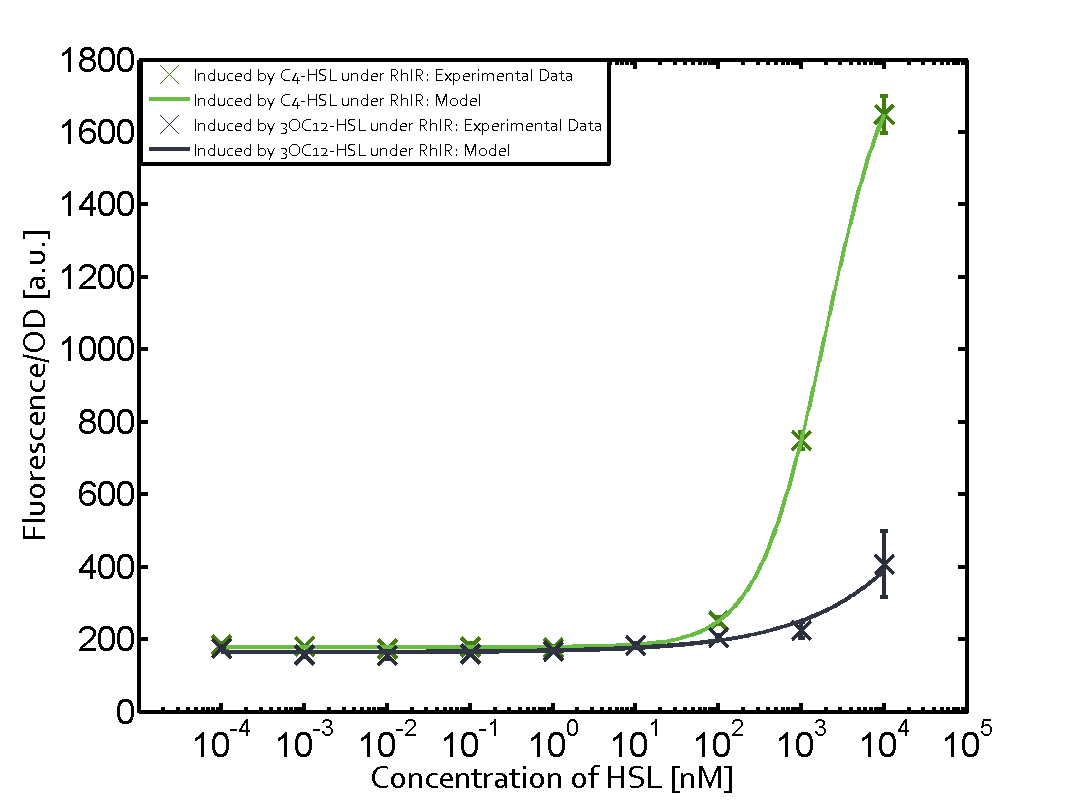

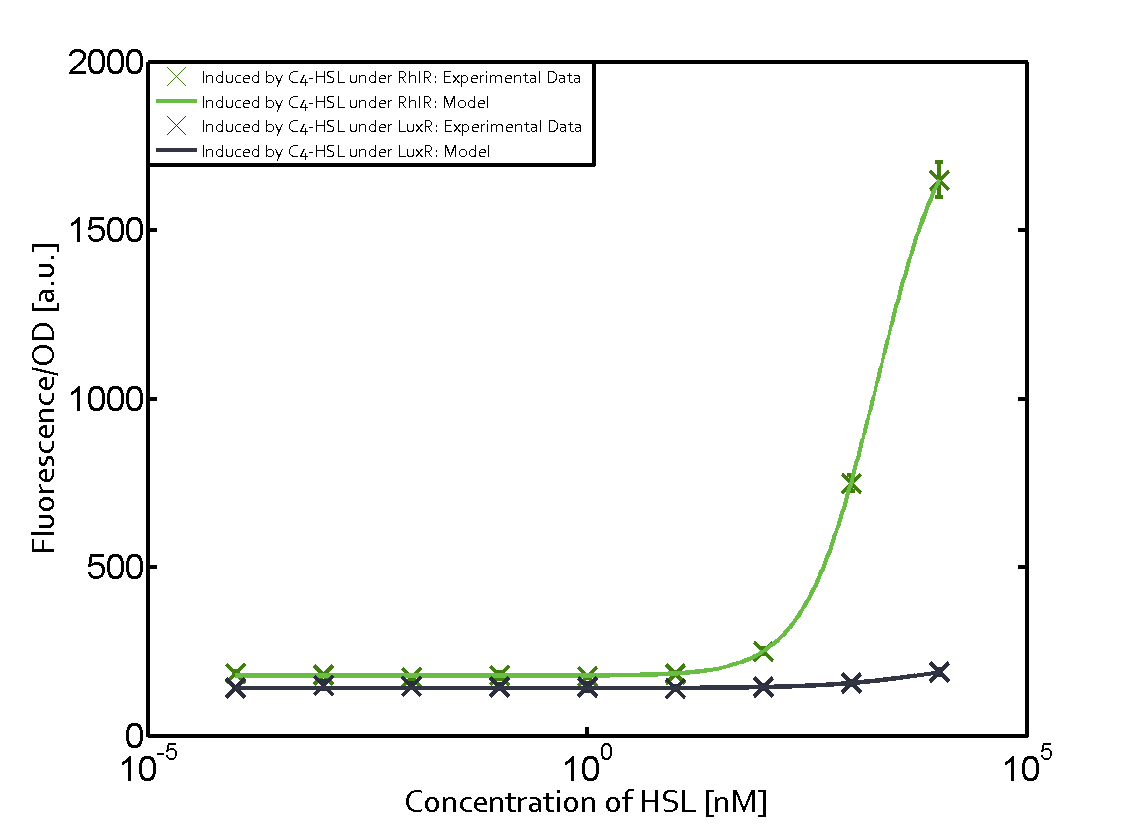

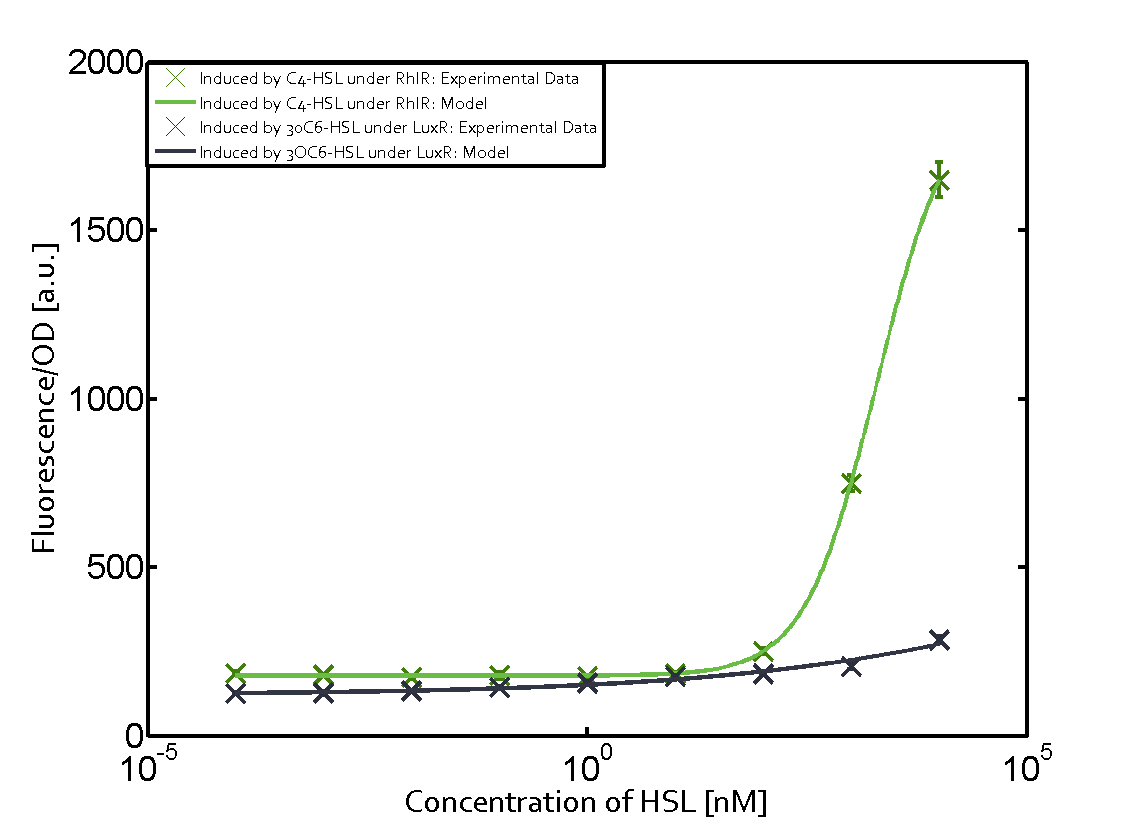

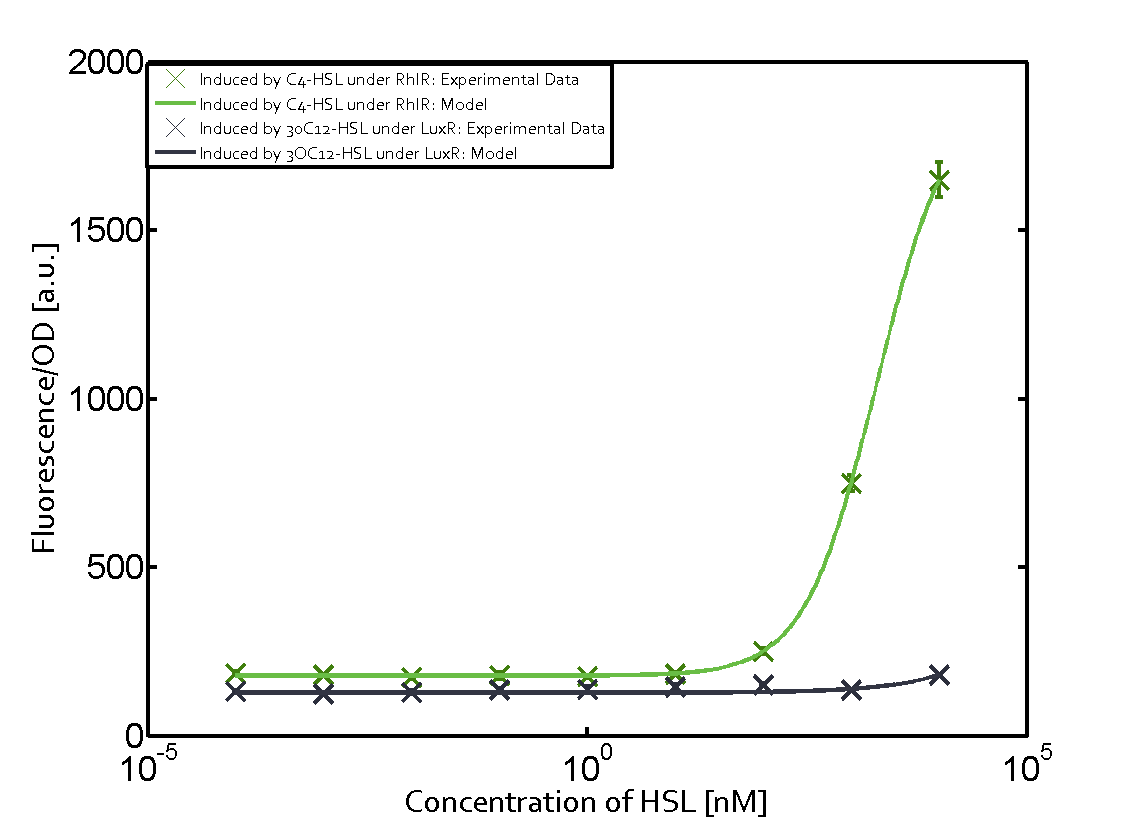

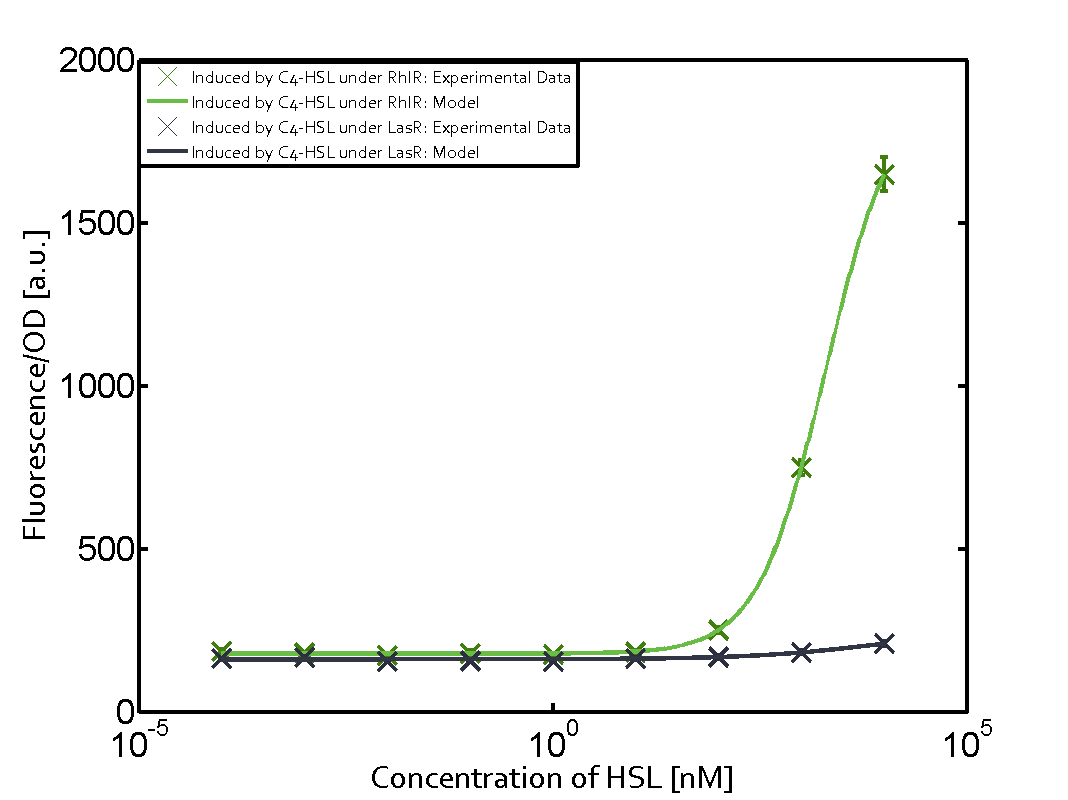

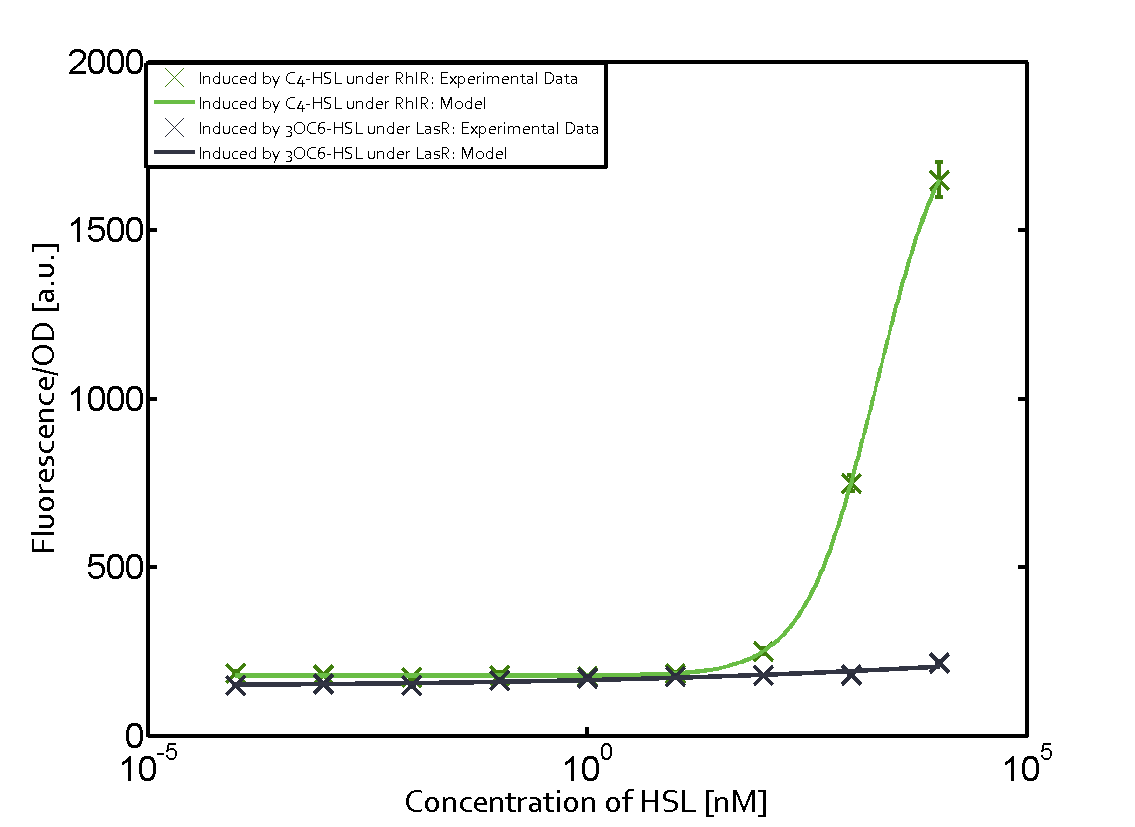

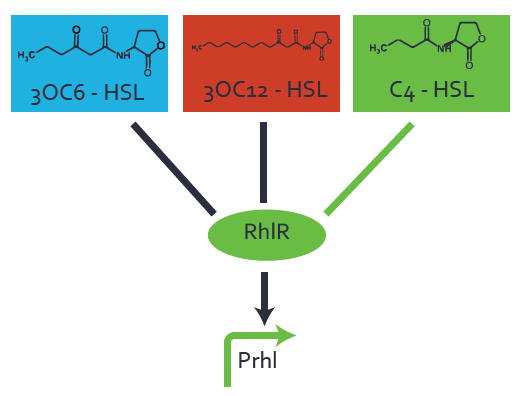

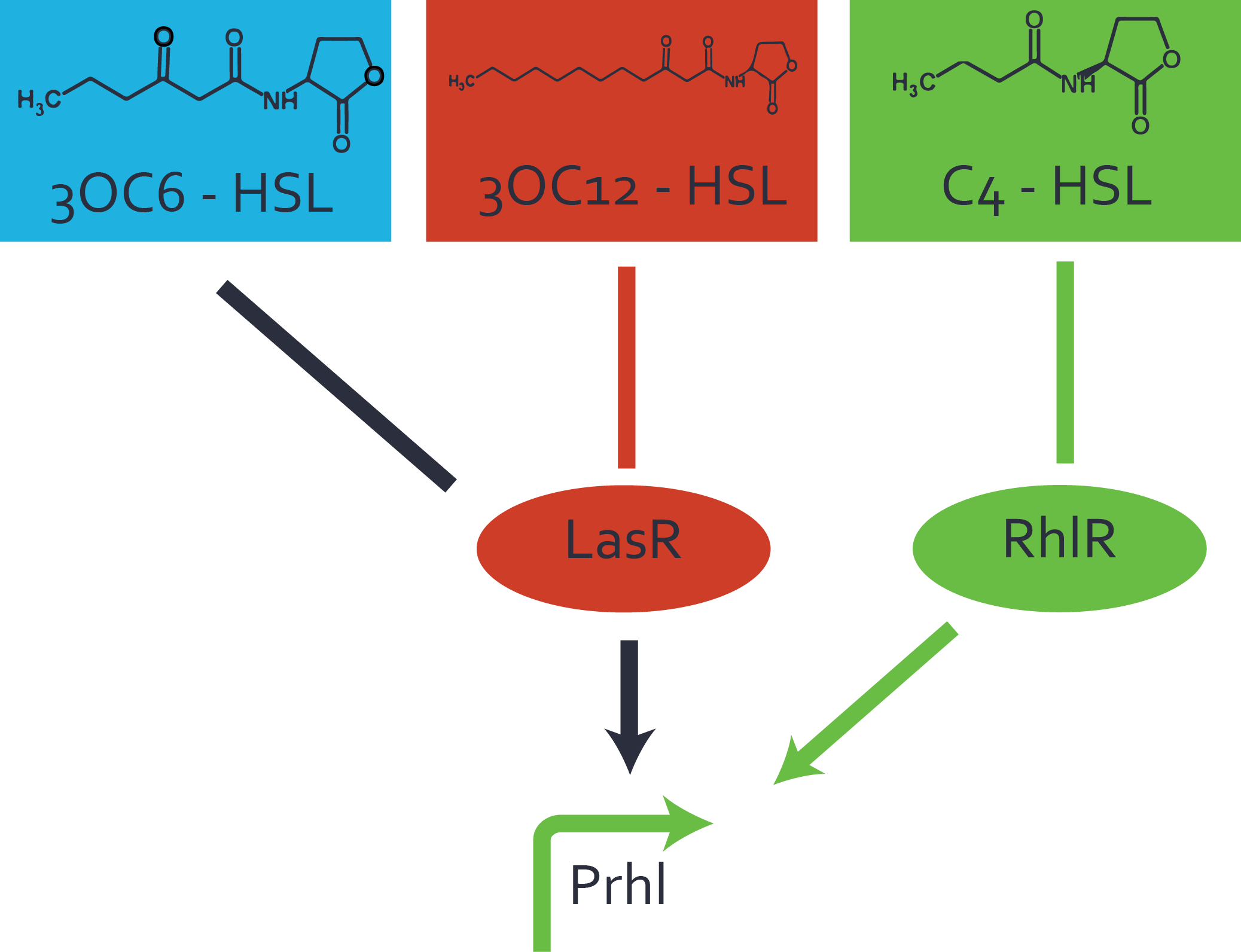

[[File:ETH Zurich 1crosstalkPrhl.png|400px|thumb|center| '''Figure 1 Overview of possible crosstalk of the [https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_C0171 RhlR]/[https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_I14017 pRhl] system with three different [[AHL|AHLs]].''' Usually, [[AHL|C4-HSL]] binds to its corresponding regulator, [https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_C0171 RhlR], and activates the [https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_I14017 pRhl] promoter (green). However, [https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_C0171 RhlR] may also bind [[AHL|3OC12-HSL]] (red) or [[3OC6HSL|3OC6-HSL]] (light blue) and then unintentionally activate [https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_I14017 pRhl].]] | [[File:ETH Zurich 1crosstalkPrhl.png|400px|thumb|center| '''Figure 1 Overview of possible crosstalk of the [https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_C0171 RhlR]/[https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_I14017 pRhl] system with three different [[AHL|AHLs]].''' Usually, [[AHL|C4-HSL]] binds to its corresponding regulator, [https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_C0171 RhlR], and activates the [https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_I14017 pRhl] promoter (green). However, [https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_C0171 RhlR] may also bind [[AHL|3OC12-HSL]] (red) or [[3OC6HSL|3OC6-HSL]] (light blue) and then unintentionally activate [https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_I14017 pRhl].]] | ||

Revision as of 11:05, 21 October 2019

This experience page is provided so that any user may enter their experience using this part.

Please enter

how you used this part and how it worked out.

Applications of BBa_J10050

User Reviews

UNIQ5caad32086859d8f-partinfo-00000000-QINU

|

••••

ETH Zurich 2014 |

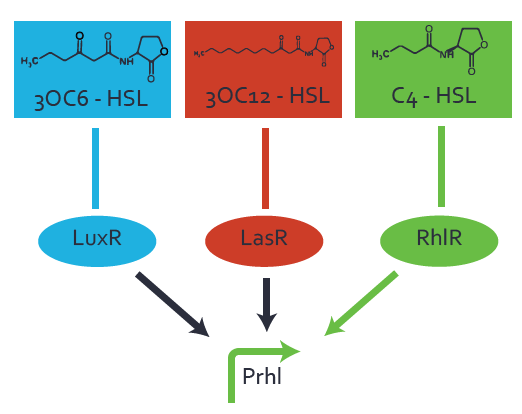

Characterization of weak promoter (BBa_J23113) and weak RBS (BBa_B0031)Differences in promoter strength had more effect on enzymatic expression compared to differences in RBS strengths as evidenced in the graphs below. Lambert_GA 2019 had originally thought that BBa_J10050 would result in the least amount of expression out of the tested combinations, but this part, along with BBa_J10051 and BBa_J10052, all shared the lowest expression out of the combinations. This is due to the translation rate not being an important factor in the determination of expression of ONP; however, the promoter strength is a significant factor. In other words, expression values are significantly different with different promoters but not with different RBS strengths.  Figure 1 Overview of possible crosstalk of the RhlR/pRhl system with three different AHLs. Usually, C4-HSL binds to its corresponding regulator, RhlR, and activates the pRhl promoter (green). However, RhlR may also bind 3OC12-HSL (red) or 3OC6-HSL (light blue) and then unintentionally activate pRhl. Second Level crosstalk: other regulatory proteins, like LuxR and LasR, bind to their natural AHL substrate and activate the pRhl promoterIn the conventional system C4-HSL binds to its corresponding regulator, RhlR, and activates the pRhl promoter (Figure 2, green). However, pRhl can potentially be activate by other regulators (LuxR, LasR), binding their corresponding regulator (figure 2, 3OC6-HSL in light blue, 3OC12-HSL in red). This leads then to unwanted gene expression (crosstalk).  Figure 2 Overview of possible crosstalk of the RhlR/pRhl system with two additional regulators (LuxR and LasR). Usually, RhlR together with inducer C4-HSL activate their corresponding promoter pRhl (green). However, pRhl may also be activated by the LuxR regulator together with 3OC6-HSL (light blue) or by the LasR regulator together with 3OC12-HSL (red). Second order crosstalk: Combination of both cross-talk levelsThe second order crosstalk describes unintended activation of pRhl by a mixture of both the levels described above. The regulator and inducer are being different from RhlR and C4-HSL, respectively, and at the same time they do not belong to the same module. For example, the inducer 3OC6-HSL (light blue), usually binding to the regulator LuxR, could potentially interact with LasR regulator (red) and together activate pRhl (green). This kind of crosstalk is explained in Figure 3.  Figure 3 Overview of possible crosstalk of the pRhl promoter with both the regulator and inducer being unrelated to the promoter and each other. Usually, RhlR together with inducer C4-HSL activate their corresponding promoter pRhl (green). However, pRhl may also be activated by another regulator together with an unrelated inducer. For example, the inducer 3OC6-HSL (light blue) may interact with the LasR regulator (red) and together activate pRhl (green). Results

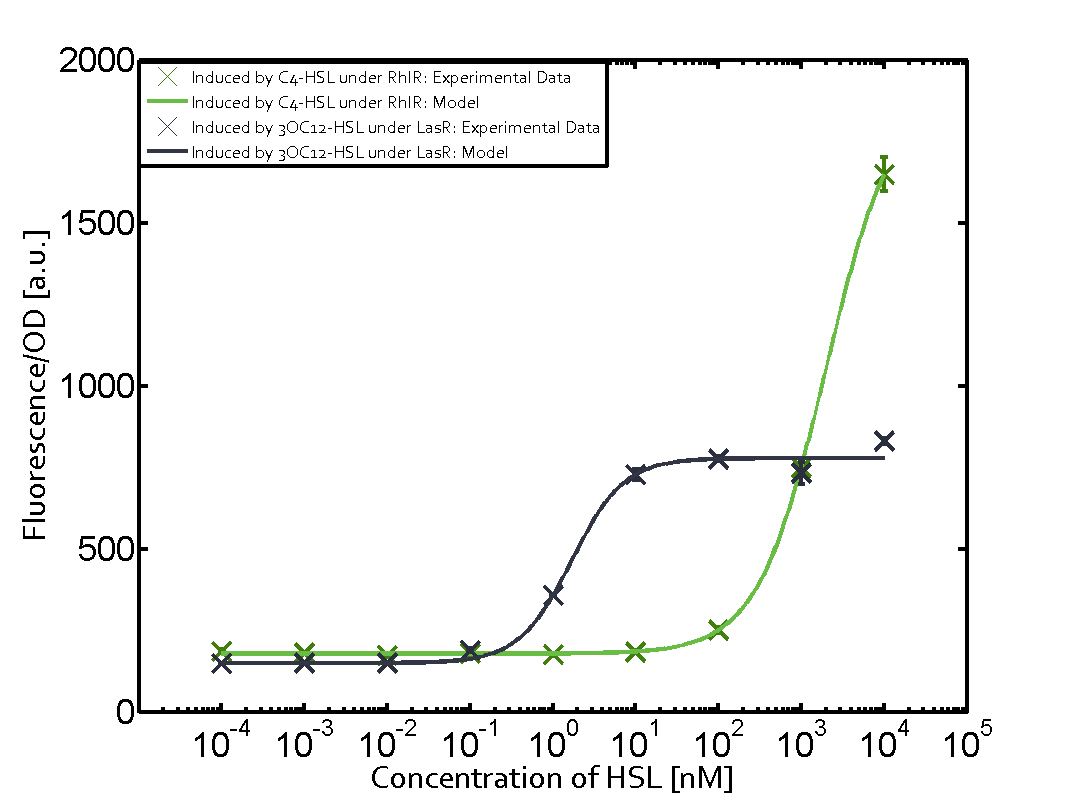

Modeling crosstalkEach experimental data set was fitted to an Hill function using the Least Absolute Residual method. The fitting of the graphs was performed using the following equation :

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Antiquity |

This review comes from the old result system and indicates that this part did not work in some test. |

UNIQ5caad32086859d8f-partinfo-00000003-QINU