Part:BBa_K3453177

Grapevine VvTrnL-UAA Toehold Switch 1.1.3 with sfGFP-LVAtag

This part is an sfGFP-LVAtag (BBa_K2675006) expression cassette under the control of the Grapevine Toehold Switch 1.1.3 (BBa K3453076) for sequence-based detection of Vitis vinifera.

It is a technical improvement of BBa_K2916068, BBa K3453170 and BBa K3453171.

Usage and Biology

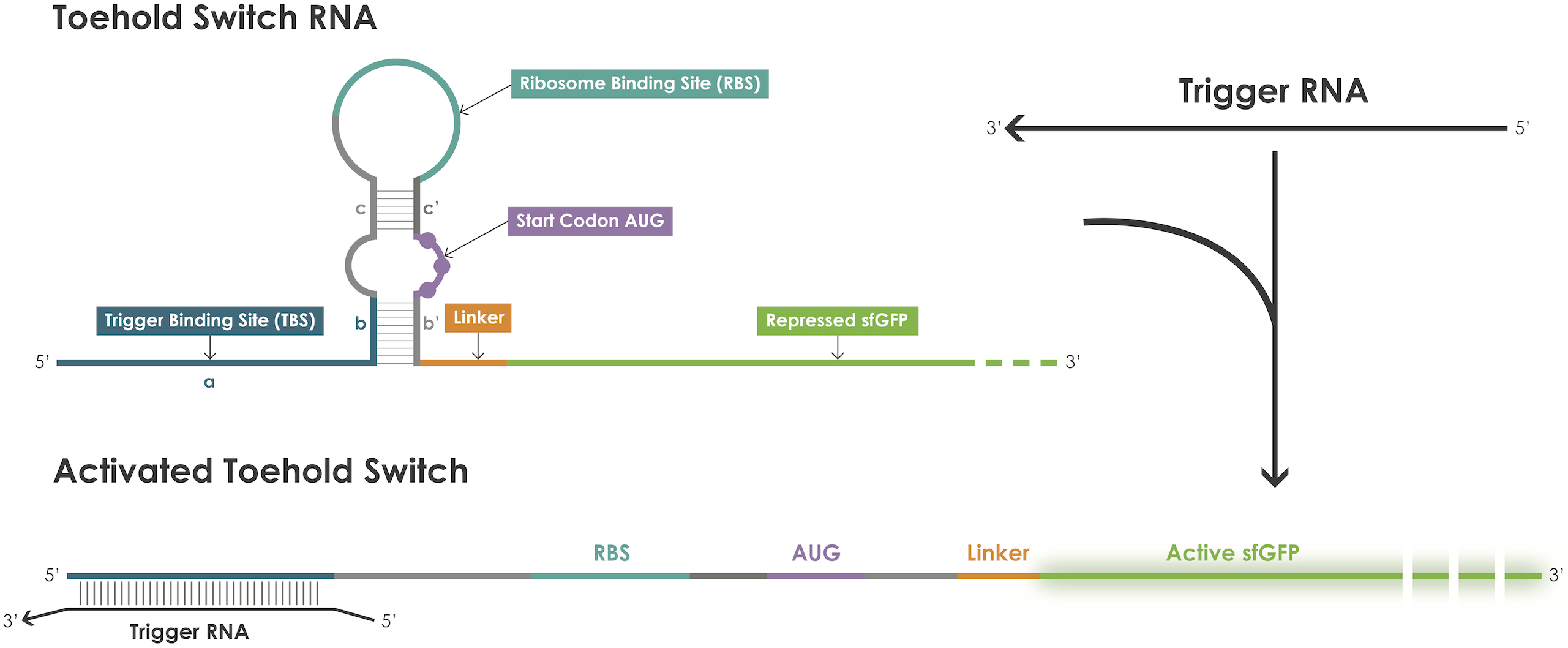

As depicted in Figure 1, a toehold switch blocks translation initiation because the RBS and the ATG start codon are embedded in the middle of a hairpin structure maintained by base pairs before and after the start codon [1]. The hairpin can be unfolded upon binding of a trigger RNA thereby exposing the RBS and the ATG start codon and thus permitting translation of the reporter protein. The binding between the trigger and the switch is dictated by RNA-RNA interactions between complementary base pairs.

Figure 1. Toehold switches principle.

In this composite part sfGFP-LVAtag (BBa_K2675006) was equipped by the Grapevine Toehold Switch 1.1.3 (BBa K3453076) and placed under the control of the T7 promoter (BBa_K2150031) and of the strong SBa_000587 synthetic terminator (BBa_K3453000).

BBa K3453076 is a technical improvement of the Grapevine VvTrnL-UAA Toehold Switch 1.1 (BBa_K2916050). Indeed, RBS strength may be may be responsible for the low sfGFP expression observed from all BBa_K2916050 (T7 promoter + grapevine switch 1.1) derived parts that we analysed (BBa_K2916068, BBa_K3453170, BBa_K3453171, BBa_K3453172). To investigate this possibility we modified the RBS stem-loop region of BBa_K2916050 and transformed it into the ‘standard’ RBS stem-loop region (BBa_K3453005) of the Series B of toehold switch sensors for Zika virus detection [2] and of the BioBits™ toeholds [3] that was used in the positive control BBa_K3453105. The resulting part (BBa K3453076) was denoted the Grapevine Switch 1.1.3. A truncated version lacking the trigger binding site (BBa_K3453078) was also designed to mimic the open (unfolded) state of this toehold switch. It’s predicted translation initiation rate in the composite part BBa_K3453178 (Figure 2) was higher compared with the truncated Grapevine Switches 1.1 (BBa_K3453072) and 1.1.2 (BBa_K3453075).

Figure 2. Translation initiation rates predicted with the Salis' RBS Calculator 2.1 [4-7].

In BBa_K2916050 (which is the T7 promoter together with grapevine switch 1.1) as well as in its derivative BBa K3453076, the trigger binding region is in the same direction as in the grapevine genome and of the trigger sequences derived from (BBa_K3453081 and BBa_K3453083). As a result, this trigger / switch pair does not interact and is not functional.

However, the hairpin structure of the grapevine switch 1.1 is predicted to be unfolded by the reverse complements of the two triggers BBa_K3453082 and BBa_K3453084 (Table 1).

| Table 1. Grapevine triggers. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Label | Part number | Transcriptional units’ part numbers | Source |

| Grapevine trigger 'short' | BBa_K3453081 | BBa_K3453181 | EPFL 2019 iGEM team personal communication |

| Grapevine trigger 'short reverse' | BBa_K3453082 | BBa_K3453182 | Reverse complement of BBa_K3453081 |

| Grapevine trigger 'long' | BBa_K3453083 | BBa_K3453183 | designed by the EPFL 2019 iGEM team and its sequence was deduced from “Amplification” page of the EPFL 2019 wiki where is described how the triggers were designed: the grapevine trigger was PCR amplified using as template the Vitis vinifera TrnL-UAA and the forward primers EC_fwd1 or EC_fwd1_T7 and the EC_rev1 reverse primer (it should be noted that the sequences of all reverse primers listed in the additional materials of this page are given as 3’-5’ sequences and not in the conventional 5’-3’ orientation). |

| Grapevine trigger 'long reverse' | BBa_K3453084 | BBa_K3453184 | Reverse complement of BBa_K3453083 |

BBa_K3453177 was constructed by PCR with the primers 5'-ATAGGTCTCACAGAGGAGATAAAGATGTCTCTGCACC-3' and 5'-ATAGGTCTCATCTGTTCTAAAGTCCGTCTCTGCACCTATCCTTTTTTTATTATCG-3' on BBa_K3453171 in pSB3T5 followed by a Golden Gate self circularisation in the presence of BsaI.

The trigger sequences (Table 1) were placed under the control of the T7 promoter and followed by the strong SBa_000587 synthetic terminator for the T7 RNA polymerase and the resulting transcriptional units were synthesized and assembled in the high copy plasmid pSB1C3.

For toehold switch characterisation we decided to use E. coli BL21 Star™(DE3) cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific), genotype F- ompT hsdSB (rB-mB-) gal dcm rne131 (DE3). As all BL21(DE3) E. coli strains, these cells contain the T7 RNA polymerase under control of the lacUV5 promoter and thus require IPTG to induce expression. The particularity of BL21 Star™(DE3) cells is that they contain a truncated version of the RNaseE gene (rne131) that leads to reduced level of mRNA degradation and thus increased RNA stability. For fluorescence measurements, E. coli cells containing switch and trigger plasmids were first grown overnight in 96-deep-well plates containing 1 mL of LB medium supplemented with 5 µg/mL tetracycline and 17.5 µg/mL chloramphenicol, then diluted by 40x into similar media. Upon reaching early log-phase, cells were further diluted 20x in 100 µL of LB medium supplemented with 5 µg/mL tetracycline, 17.5 µg/mL chloramphenicol and 10 µM IPTG in an opaque wall 96-well polystyrene microplate, the COSTAR 96 (Corning). The plate was incubated at 37°C at 200 rpm and the sfGFP fluorescence (λexcitation 483 nm and λemission 530 nm) and OD600nm were measured every 10 min for 24 hours in a CLARIOstar (BMGLabtech) plate reader. Fluorescence values were normalised by OD600nm and, using the calibration curves presented on the ‘Measurement’ page of our wiki, we converted the arbitrary units into Molecules of Equivalent FLuorescein (MEFL) / particle.

The results presented in figures 3, 4 and 5 show that this part is functional: sfGFP expression was observed only when the BBa_K3453177 was tested in the presence of the two grapevine triggers, both in reverse direction.

However, we were unable to detect a significant increase of MEFL/particle values (Figure 6) upon RBS change (compare the expression of sfGFP under the control of the Grapevine Switches 1.1 and 1.1.2 in BBa_K3453171 and BBa_K3453177 respectively).

The results presented in Figure 3 show also that the sfGFP expression was readily detected in the positive controls and that the two RBS (BBa_K2675017 and BBa_K3453005) have comparable strength. As expected, no fluorescence was detected in the negative controls as either the sfGFP gene was not present or the promoter and the RBS were absent.

Figure 3. In vivo characterization of sfGFP expression by E. coli BL21 Star™(DE3) cells harbouring the grapevine toehold switch 1.1.3 in BBa_K3453177 and the 'short' and 'long' grapevine triggers in both forward and reverse orientation (BBa_K3453181, BBa_K3453182, BBa_K3453183 and BBa_K3453184). The negative controls have been performed with an empty pSB3T5, pSB1C3 (no trigger) and BBa_K3453103 (no promoter, no RBS) and the positive controls with BBa_K3453104 and BBa_K3453105. The data and error bars are the mean and standard deviation of at least three measurements on independent biological replicates.

Figure 4. MEFL / Particle fold changes of the grapevine toehold switch 1.1.3 in BBa_K3453177 in the presence of the 'short' and 'long' grapevine triggers in both forward and reverse orientation (BBa_K3453181, BBa_K3453182, BBa_K3453183 and BBa_K3453184) compared to the MEFL / Particle value in the absence of the trigger.

Figure 5: Pictures of E. coli BL21 Star™(DE3) cells harbouring this part and in the presence of the 'short' and 'long' grapevine triggers in both forward and reverse orientation (BBa_K3453181, BBa_K3453182, BBa_K3453183 and BBa_K3453184). The negative control was performed with an empty pSB1C3 (no trigger).

BBa_K3453177 is one of the parts that we designed and characterised in order to uncover (some) of the reasons why the sequence upstream of the natural ATG of sfGFP has a negative influence on its expression in BBa K3453170, BBa K3453171 and BBa K3453172.

These parts are listed in Table 2 and the results of their characterisation summarised in Figure 6. All details are available on their individual pages in the registry and the full story can be read on the 'Contribution' page of our wiki.

| Table 1. Grapevine toehold switches 1.1 and derivatives. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Label | Toehold Switch Part Number | Toehold Switch + sfGFP Part Number | Toehold Switch + sfGFP-LVAtag Part Number |

| Grapevine VvTrnL-UAA Toehold Switch 1.1 | BBa_K2916050 | BBa_K2916068 & BBa_K3453170 | BBa_K3453171 |

| Truncated Grapevine VvTrnL-UAA Switch 1.1 (no trigger binding site) | BBa_K3453072 | BBa_K3453172 | |

| Grapevine VvTrnL-UAA Toehold Switch 1.1.2 | BBa_K3453073 | BBa_K3453173 | BBa_K3453174 |

| Truncated Grapevine VvTrnL-UAA Switch 1.1.2 (no trigger binding site) | BBa_K3453075 | BBa_K3453175 | |

| Grapevine VvTrnL-UAA Toehold Switch 1.1.3 | BBa_K3453076 | BBa_K3453176 | BBa_K3453177 |

| Truncated Grapevine VvTrnL-UAA Switch 1.1.3 (no trigger binding site) | BBa_K3453078 | BBa_K3453178 | |

Figure 6. In vivo characterization of sfGFP expression by E. coli BL21 Star™(DE3) cells harbouring the grapevine toehold switches 1.1 (Table 2) and the 'short' and 'long' grapevine triggers in both forward and reverse orientation (BBa_K3453181, BBa_K3453182, BBa_K3453183 and BBa_K3453184). The negative controls have been performed with an empty pSB3T5, pSB1C3 (no trigger) and BBa_K3453103 (no promoter, no RBS) and the positive controls with BBa_K3453104 and BBa_K3453105. The data and error bars are the mean and standard deviation of at least three measurements on independent biological replicates.

This BBa_K3453177, as well as BBa_K3453170, BBa_K3453171, BBa_K3453173, BBa_K3453174 and BBa_K3453176 are technical improvements of BBa_K2916068. However, all these six improved parts are functional in the presence of a trigger artificially expressed in E. coli in reverse orientation. They are not able to detect the presence of an RNA naturally expressed in grapevine because the trigger binding site is not in a compatible orientation. But that is another story, and we invite the reader to discover it on the 'Improvement' page of our wiki.

References

[1] Green AA, Silver PA, Collins JJ, Yin P. Toehold switches: de-novo-designed regulators of gene expression. Cell (2014) 159: 925-939.

[2] Pardee K, Green AA, Takahashi MK, Braff D, Lambert G, Lee JW, Ferrante T, Ma D, Donghia N, Fan M, Daringer NM, Bosch I, Dudley DM, O'Connor DH, Gehrke L, Collins JJ. Rapid, low-cost detection of Zika virus using programmable biomolecular components. Cell (2016) 165, 1255-1266.

[3] Huang A, Nguyen PQ, Stark JC, Takahashi MK, Donghia N, Ferrante T, Dy AJ, Hsu KJ, Dubner RS, Pardee K, Jewett MC, Collins JJ. BioBits™ Explorer: A modular synthetic biology education kit. Sci Adv (2018) 4, eaat5105.

[4] Salis HM, Mirsky EA, Voigt CA. Automated design of synthetic ribosome binding sites to control protein expression. Nature Biotechnology (2009) 27: 946–950.

[5] Espah Borujeni A, Channarasappa AS, Salis HM. Translation rate is controlled by coupled trade-offs between site accessibility, selective RNA unfolding and sliding at upstream standby sites. Nucleic Acids Research (2014) 42: 2646–2659.

[6] Espah Borujeni A, Salis HM. Translation initiation is controlled by RNA folding kinetics via a ribosome drafting mechanism. Journal of the American Chemical Society (2016) 138: 7016–7023.

[7] Espah Borujeni A, Cetnar D, Farasat I, Smith A, Lundgren N, Salis HM. Precise quantification of translation inhibition by mRNA structures that overlap with the ribosomal footprint in N-terminal coding sequences. Nucleic Acids Research (2017) 45: 5437–5448.

Sequence and Features

- 10COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[10]

- 12COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[12]

- 21COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[21]

- 23COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[23]

- 25INCOMPATIBLE WITH RFC[25]Illegal AgeI site found at 146

- 1000COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[1000]

| None |