Part:BBa_K801060

(+)-Limonene synthase 1 with Strep-tag and yeast consensus sequence.

This part contains the (+)-Limonene synthase 1 of Citrus limon. It is preceeded by the yeast consensus sequence for improved expression and carries a C-Terminal Strep-tag for purification or detection by westernblot. It is an improved version of BBa_I742111. Also see the experience pages of BBa_I742111 and BBa_K118025.

Background and principles

Limonene is a cyclic terpene and a major constituent of several citrus oils (orange, lemon, mandarin, lime and grapefruit). It is a chiral liquid with the molecular mass of 136.24 g/mol. The (R)-enantiomer smells like oranges and is content of many fruits, while the (S)-enantionmer has a piney odor http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11605760 Fietzek et al., 2001. Therefore d-limonene ((+)-limonene, (R)-enantiomer) is used as a component of flavorings and fragrances.

Biosynthesis

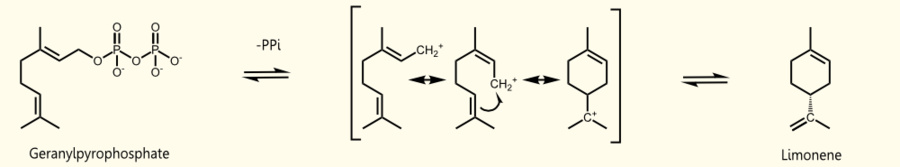

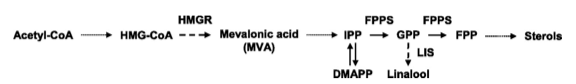

Limonene is produced by limonene synthase which uses geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP) as educt which is the universal precursor of monoterpenoids. (+)-limonene synthase from Citrus limon consists of 606 aminoacids (EC=4.2.3.20) and catalyzes the following reaction: Geranyl pyrophosphate = (+)-(4R)-limonene + diphosphate (see Fig. 1).

Saccharomyces cerevisiae produces geranyl pyrophosphate via the mevalonate pathway (see Fig. 2) where it occurs exclusively as an intermediate of farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) synthesis http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17096665 Oswald et al., 2007. It has been established that S. cerevisiae has enough free GPP to be used by exogenous monoterpene synthases to produce monoterpenes under laboratory and vinification conditions [[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18155949 Herrero et al., 2008], [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17096665 Oswald et al., 2007]].

The molecular and physiological effects of limonene

Flavour and Aliment

Because of its pleasant Citrus flavour and very low toxicity (oral LD50 for mice = 5.6 and 6.6 g/kg body weight), d-limonene is widely used as a flavor and fragrance additive. Therefore it is listed in the Code of Federal Regulations as generally recognized as safe (GRAS) http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Food/FoodIngredientsPackaging/GenerallyRecognizedasSafeGRAS/GRASListings/UCM264589.pdf FDA for a flavoring agent and can be found in common food items such as fruit juices, soft drinks, baked goods, ice cream, and pudding in typical concentrations of 50 ppm till 2,500 ppm, respectively http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18072821 Sun, 2007. Hence the normal daily consume of d-limonene is 0,27 mg/kg body weight per day http://www.mri.bund.de/fileadmin/Institute/PBE/Sekundaere_Pflanzenstoffe/Monoterpene.pdf Watzl, 2002. As natural compound of plants limonene has practical advantages with regard to availability, suitability for oral apllication, regulatory approval and mechanisms of action and does not pose a mutagenic, carcinogenic, or nephrotoxic risk to humans http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18072821 Sun, 2007.

Cancer inhibition

Monoterpenes have anti carcinogenic effects in animal experiments. It has been shown to inhibit rat mammary, gastric, lung and skin tumor development by several discussed mechanisms like apoptosis induction and modulation of oncogene signal transduction [[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=Tsuda%20limonene%202004 Tsuda et al., 2004], [http://www.mri.bund.de/fileadmin/Institute/PBE/Sekundaere_Pflanzenstoffe/Monoterpene.pdf Watzl, 2002]]. So d-limonene induces phase I and phase II carcinogen-metabolizing enzymes (cytochrome p450), which metabolize carcinogens to less toxic forms and prevent the interaction of chemical carcinogens with DNA. It also inhibits tumor cell proliferation, acceleration of the rate of tumor cell death and/or induction of tumor cell differentiation. Furthermore, d-limonene regulate cell growth and/or transformation by inhibiting protein isoprenylation http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18072821 Sun, 2007.

Solvent for Gallstones

Furthermore it is used as excellent solvent of cholesterol, therefore d-limonene has been used clinically to dissolve cholesterol-containing gallstones http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18072821 Sun, 2007. A study with 200 patients reported a direct infusion of 20-30 ml D-limonene (97% solution) completely or partially dissolved gallstones in 141 patients. Stones completely dissolved in 96 cases (48%); partial dissolution was observed in 29 cases (14.5%); and in 16 cases (8%) complete dissolution was achieved with the inclusion of hexamethaphosphate (HMP), a chelating agent that can dissolve bilirubin calcium stones http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1988264 Igimi et al., 1991. Because of its gastric acid neutralizing effect and its support of normal peristalsis, it also has been used for relief of heartburn http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18072821 Sun, 2007.

Characterization

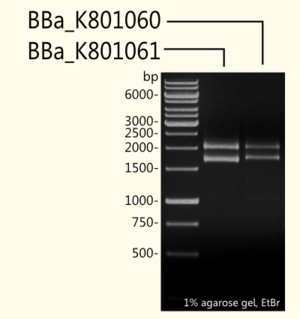

Gel Picture of finished constructs

We wanted to analyze (+)-Limonene synthase 1 expression in yeast depending on existence of a consensus sequence. For further experiments ligation and cloning of (+)-Limonene synthase 1 in a new yeast expression vector pTUM100 for protein expression in yeast and in pSB1C3 for submissions for iGEM competition were made. To check success of ligation, double-stranded DNA fragments were separated by length via agarose gel-electrophoresis using ethidium bromide as a nucleic acid stain.

(+)-Limonene synthase 1 coding region without yeast consensus sequence [BBa_K801061] in pSB1C3 is shown next to (+)-Limonene synthase 1 with Strep-tag and yeast consensus sequence [BBa_K801060] after restriction digest with EcoR-1 and Pst-1 restriction enzymes. As expected, the 1665 bp fragment of [BBa_K801061] and the 1708 bp fragment of [BBa_K801060] could be detected additionally to the pSB1C3 vector (2070 bp).

Investigation of the yeast consensus sequence

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC340751/ Hamilton et al., 1987 reported of a consensus sequence upstream of the AUG start codon in yeast. Although not as strong as the mammalian Kozak translation initiation sequence, the yeast consensus sequence is thought to have a 2–3-fold effect on the efficiency of translation initiation http://tools.invitrogen.com/content/sfs/manuals/pyes2_man.pdf pYES2 manual.

We designed duplicates of limonene synthase encoding biobricks; one having the yeast consensus sequence, the other one not having the consensus sequence.

We have not been able to show significant differences in expression between the two biobricks [BBa_K801065 and BBa_K801060] via coomassie staining and western blot. The difficulties of showing the difference via SDS-page may result from variations in the amount of protein applied.

Our in vivo analysis indicates that the consensus sequence does lead to a 2-3-fold enhanced expression in yeast, though (see Fig. 6B). This is consistent with findings of others http://tools.invitrogen.com/content/sfs/manuals/pyes2_man.pdf pYES2 manual.

Purification of recombinant limonene synthase

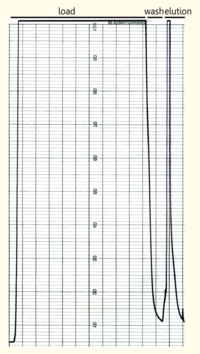

Streptavidin affinity chromatography

The yeast cell extract that was obtained by cell lyse using glass beads of 0,5mm was centrifuged at 11000 RPM in a SLA-3000 rotor for 60 minutes and subsequently dialysed against 5 liters of 1x Streptavidin Affinity buffer (SA-buffer)over night. The cell extract was then filtrated using a syringe filter with a pore size of 0.45μm and susequently applied on a SA-column. After the sample was applied the column was washed using 1xSA buffer until a base line was reached and then the bound protein was eluted using 5mM Biotin in 1x SA buffer. The chromatogramm of the purification is shown on the left side.

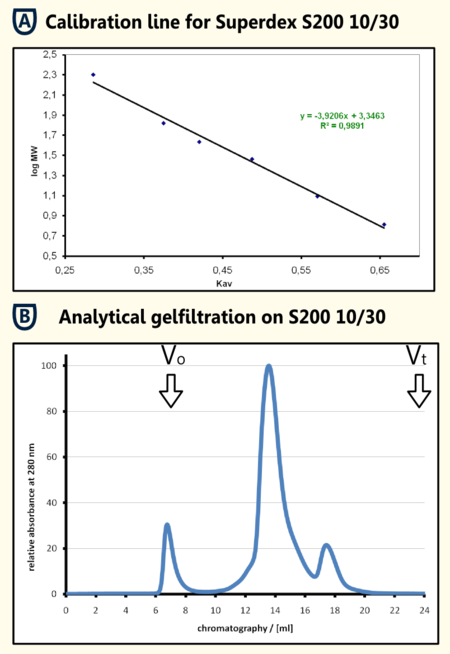

Gelfiltration of the SA purified protein The protein sample that was eluted from the SA-column was concentrated using a centrifugation concentrator with a molecular size limit of 30 kDA and filtrated afterwards. From this solution 250μl were applied on a analytical gel filtration colum Superdex 200 10/30 with BSA as running buffer at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. In the chromatogramm (shown in the figure on the right in section B)there is a aggregation peak that may be caused by the preceding concentration at the exclusion limit and a major peak at an elution volume of 13.580 ml. The calibration line that was obtained from the calibration proteins b-amylase, alcohol dehydrogenase, BSA, Obalbumine, carboanhydrase, cytochrome C and Aprotinin filtrated with the same experimental setup resulted in a regression line with the formula y = -39206 x + 3.3463. When calculating from the elution volume of the limonene synthase a apparent molecular mass of 70.1 kDa could be determinded. This fits quite well the theoretical molecular mass that was calculated using [http://web.expasy.org/cgi-bin/protparam/protparam ExPASy ProtParam] to be 65977.1 Da. The four killo daltons difference could also be caused by posttranslational modifications which should be tested using mass spectromety.

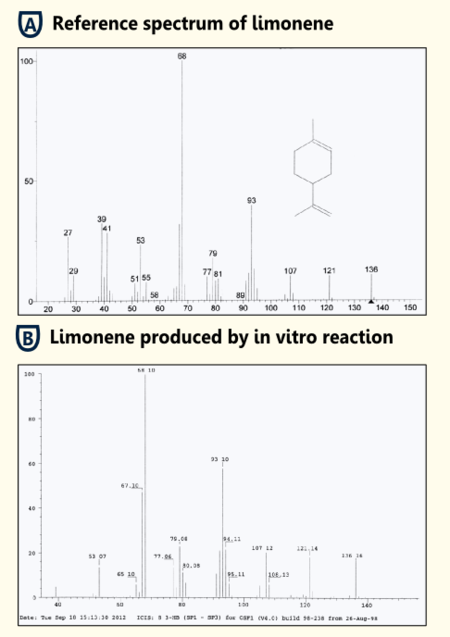

In vitro detection of limonene

To test the functionality of purified limonene synthase in vitro, we used an optimized protocol of an enzyme assay with extraction of http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17662687 Landmann et al, 2007. The limonene synthase was purified via Strep-tag. The enzyme assay was carried out in 25 mM Tris-HCl buffer with 5% Glycerol, 1mM DTT and cofactors (10 mM MgCl2, 1 mg/ml BSA). 50 µM substrate (geranyl pyrophosphate) and 10 ng purified recombinant limonene synthase were added to the reaction batch. Negative controls were reaction batches without enzyme. The reaction was incubated for 15 min at room temperature. Afterwards limonene was extracted with pentane, dried with sodiumsulfate and reduced under a stream of nitrogen. Three replicates of both sample and negative control were done.

The pentane extracts were analyzed with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry ("5890 Series II GC" coupled to a "Finnigan Mat 55 S MS") to identify the enzymatically synthesized products.

All enzyme reactions (three replicates) led to the production of limonene while the negative controls did not show limonene. Therefore, we showed that our purified limonene synthase is functional and leads to the production of limonene.

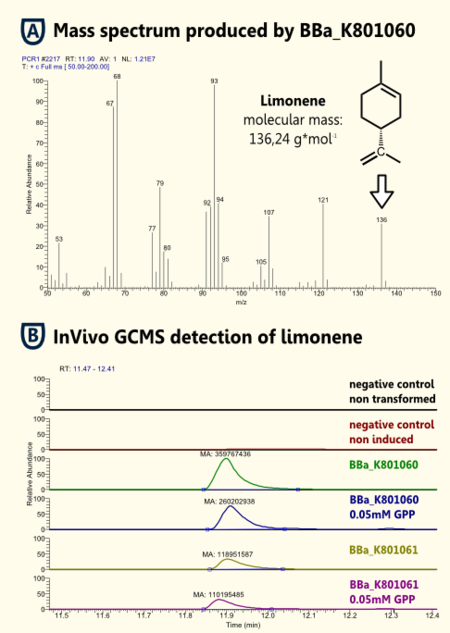

In vivo detection of limonene

Because limonene is a VOC (volatile organic compound) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15763095 Pierucci et al., 2005, we expected an arbitrarily amount of limonene in the gaseous phase above the cell culture supernatant as in the cell culture. Therefore, we measured limonene via headspace (SPME needle) GC-MS.

We showed limonene to be produced by the yeasts that were transformed with pTUM104 carrying limonene synthase coding regions (see BBa_K801061 and BBa_K801060).

We detected more limonene in the sample that contained a limonene synthase with consensus sequence. Hence, we showed that the yeast consensus sequence might increase the expression of limonene synthase and therefore lead to enhanced limonene production.

Furthermore, we could not detect a significant difference between samples that had additional GPP (educt) versus the ones that did not. This might be due to the inability of GPP to diffuse into the cells (hydrophilic character). Since we were able to detect limonene in both samples, it implies that the GPP present in the cells is sufficient for limonene production. This is consistent with the findings of [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18155949| [Herrero et al., 2008]] that showed that S. cerevisiae cells (from laboratory and wine strains) contain enough free GPP to be catalytically transformed by monoterpene synthases into monoterpenes.

Detection of limonene in beer

A first attempt to use our genetically engineered yeasts to brew a SynBio Beer were conducted using a transient transfection with a constitutive promoter. The drawback is that in the gyle the selection pressure is not preserved and the loss of the plasmid is possible.

Three liters of gyle were inoculated with 100ml of a stationary yeast culture grown in YPD that was transiently transfected with a plasmid harboring a constitutive expression cassette for the limonene synthase.

We analyzed this first beer for limonene content via headspace (SPME needle) GC-MS. Unfortunately we could not yet proof a significant difference between the beer containing limonene and the negative control beer. This might be due to a loss of the plasmid which encodes limonene synthase. We will try to integrate the limonene synthase expression cassette into the genome of yeast and afterwards we will repeat the experiment.

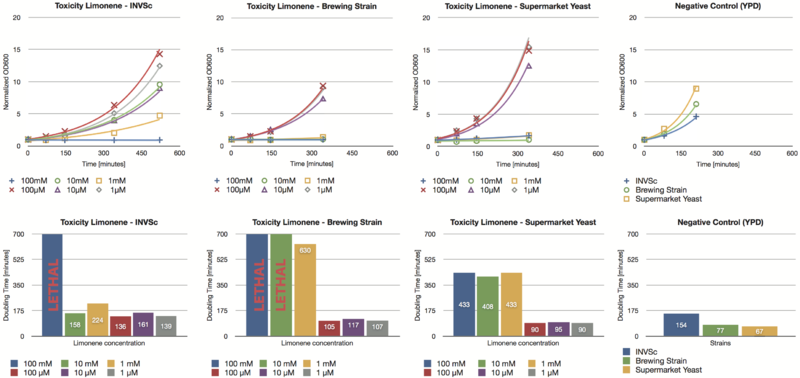

Toxicity Assay

To establish whether limonene has an effect on yeast cells , we inoculated three different yeast strains with different concentrations of limonene. Limonene was added to the medium and the used yeast strains were the laboratory strain INVSc1, a strain which is used for brewing beer and a strain which can be purchased in a supermarket.

Limonene at high concentrations affects the growth of yeast cells. We could show an inhibition of growth at 1 mM and even a lethal effect at 100 mM. At lower concentrations (1 µM, 10 µM, 100 µM) no inhibition could be observed. The growth rates of yeast cells which were incubated with low concentrations of limonene do not show a difference compared to the negative control (incubation of analogous yeast strains with YPD without limonene).

The in vivo GCMS detection of limonene [B] displayed a concentration of 50 µM. Hence the amount of limonene we will produce with the modified yeast will not reach a toxic concentration at all.

References

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11605760 Fietzek et al., 2001 Fietzek, C., Hermle, T., Rosenstiel, W., Schurig, V. (2001) Chiral discrimination of limonene by use of beta-cyclodextrin-coated quartz-crystal-microbalances (QCMs) and data evaluation by artificial neuronal networks. Fresenius J Anal Chem., 371(1):58-63.

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC340751/ Hamilton et al., 1987 Hamilton, R., Watanabe, C. K., De Boer, A. H. (1987) Compilation and comparison of the sequence context around the AUG startcodons in Saccharomyces cerevisiae mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res., 15(8):3581–3593.

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18155949 Herrero et al., 2008 Herrero, O., Ram ́on, D., and Orejas, M. (2008). Engineering the Saccharomyces cerevisiae isoprenoid pathway for de novo production of aromatic monoterpenes in wine. Metab Eng, 10(2):78–86.

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1988264 Igimi et al., 1991 Igimi, H., Tamura, R., Toraishi, K., Yamamoto, F., Kataoka, A., Ikejiri, Y., Hisatsugu, T., Shimura, H. (1991). Medical dissolution of gallstones. Clinical experience of d-limonene as a simple, safe, and effective solvent. Dig Dis Sci., 36(2):200-8.

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17662687 Landmann et al., 2007 Landmann, C., Fink, B., Festner, M., Dregus, M., Engel, K.-H., and Schwab, W. (2007). Cloning and functional characterization of three terpene synthases from lavender (Lavandula angustifolia). Arch Biochem Biophys, 465(2):417–29.

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12084056 Lücker et al., 2002 Lücker, J., El Tamer, M. K., Schwab, W., Verstappen, F. W. A., van der Plas, L. H. W., Bouwmeester, H. J., and Verhoeven, H. A. (2002). Monoterpene biosynthesis in lemon (Citrus limon). cDNA isolation and functional analysis of four monoterpene synthases. Eur J Biochem, 269(13):3160–71.

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17096665 Oswald et al., 2007 Oswald, M., Fischer, M., Dirninger, N., and Karst, F. (2007). Monoterpenoid biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res, 7(3):413–21.

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15763095 Pierucci et al., 2005 Pierucc, P., Porazzi, E., Martinez, MP., Adani, F., Carati, C., Rubino, FM., Colombi, A., Calcaterra, E., Benfenati, E. (2005). Volatile organic compounds produced during the aerobic biological processing of municipal solid waste in a pilot plant. Chemosphere, 59(3):423-30.

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20675444 Rico et al., 2010 Rico, J., Pardo, E., and Orejas, M. (2010). Enhanced production of a plant monoterpene by overexpression of the 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme a reductase catalytic domain in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol, 76(19):6449–54.

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18072821 Sun, 2007 Sun, J. (2007). D-limonene: safety and clinical applications. Altern Med Rev, 12(3):259–64.

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=Tsuda limonene 2004 Tsuda et al., 2004 Tsuda, H., Ohshima, Y., Nomoto, H., Fujita, K., Matsuda, E., Iigo, M., Takasuka, N., Moore, MA. (2004). Cancer prevention by natural compounds. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 19(4):245-63.

- http://www.mri.bund.de/fileadmin/Institute/PBE/Sekundaere_Pflanzenstoffe/Monoterpene.pdf Watzl, 2002 Watzl, B. (2002). Monoterpene. Ernährungs-Umschau 49 Heft 8. 322-324.

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9724535 Williams et al., 1998 Williams, D. C., McGarvey, D. J., Katahira, E. J., and Croteau, R. (19

Sequence and Features

- 10COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[10]

- 12COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[12]

- 21COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[21]

- 23COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[23]

- 25COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[25]

- 1000INCOMPATIBLE WITH RFC[1000]Illegal BsaI site found at 1683

Illegal SapI.rc site found at 107

//cds/biosynthesis

//chassis/eukaryote/yeast

| None |