Part:BBa_K1980010

pCopA TAT Csp1 sfGFP with divergent CueR

Description

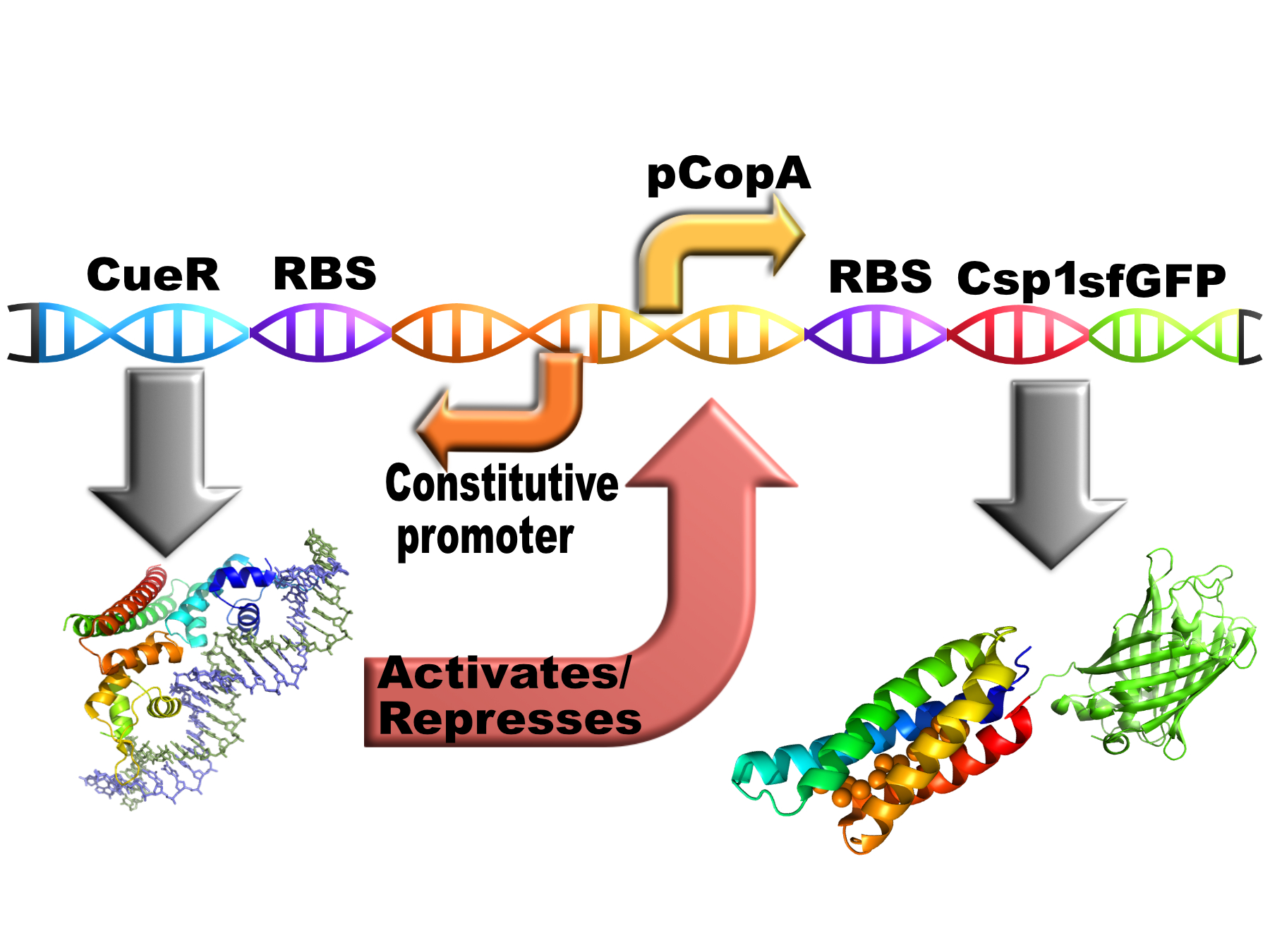

This part contains the bacterial copper chelator Csp1 (Copper Storage Protein 1) with a C-terminal sfGFP tag (connected with short hydrophilic flexible linker) behind the pCopA promoter with constitutively expressed CueR (a bacterial copper sensitive repressor/activator) in the biobrick.

Sequence and Features

- 10COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[10]

- 12INCOMPATIBLE WITH RFC[12]Illegal NheI site found at 438

Illegal NheI site found at 461 - 21INCOMPATIBLE WITH RFC[21]Illegal XhoI site found at 1466

- 23COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[23]

- 25INCOMPATIBLE WITH RFC[25]Illegal NgoMIV site found at 1028

- 1000COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[1000]

Usage and Biology

E. coli cells use a protein called CueR to regulate the cytoplasmic copper concentration. CueR is a MerR-type regulator with an interesting mechanism of action whereby it can behave as a net activator or a net repressor under different copper concentrations through interaction with RNA polymerase(1). CueR forms dimers consisting of three functional domains (a DNA-binding, a dimerisation and a metal-binding domain). The DNA binding domains bind to DNA inverted repeats called CueR boxes with the sequence:

CCTTCCNNNNNNGGAAGG

This box is present at the promoter regions of the copper exporting ATPase CopA, some molybdenum cofactor synthesis genes and the periplasmic copper oxidase protein CueO.(2)

This is how the construct is intended to work in vivo

Experience

We cloned pCopA TAT Csp1 sfGFP with divergent expressed CueR from a gBlock into the shipping plasmid pSB1C3. E. coli strain MG1655 was transformed using the specific recombinant plasmid and a 5ml culture of a transformed colony was grown overnight. The functionality of the construct was tested using plate reading, flow cytometry and microscopy

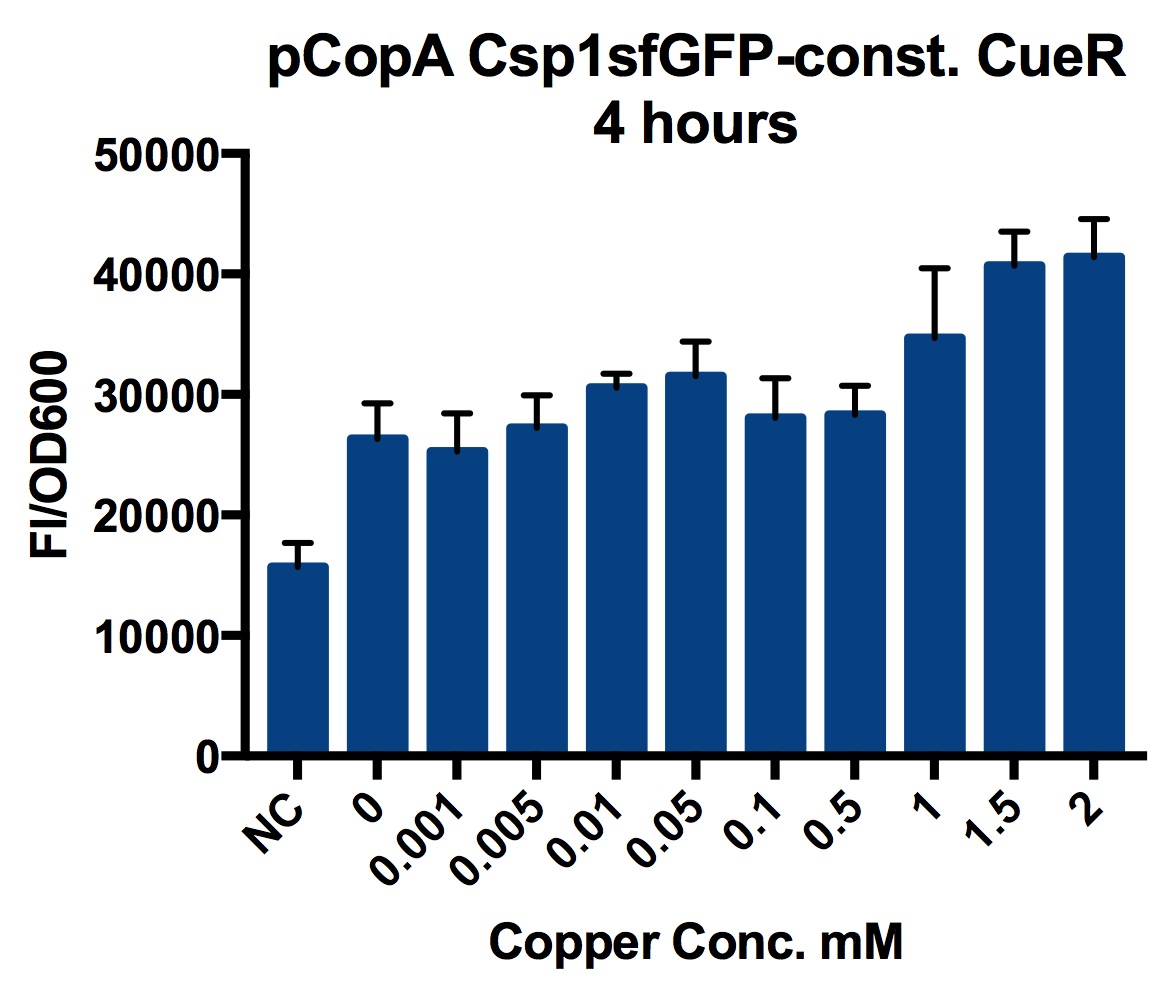

Plate Reader

We tested the promoter with the fluorescent protein sfGFP (a form of GFP with excitation/emission maxima at 485-512nm and 520nm).

To account for the number of cells present at different copper concentrations and different times we measured the optical density (OD) as a proportional measure of the number of cells present.

A range of copper concentrations were prepared from stock solutions. A large volume plate was then prepared with 10μl of copper solution, 10μl of overnight culture and 980μl of broth with antibiotic. This resulted in a 1 in 100 dilution of the copper solutions prepared.

This large-volume plate was then centrifuged to mix the solutions and then 200μl transferred to a small-volume plate with a clear lid and then placed in the plate reader.

Four biological repeats of the part to be tested in MG1655 at ten different copper concentrations were measured as well as four repeats of a MG1655 negative control.

The plate reader measured the fluorescence and OD every ten minutes for at least 12 hours, shaking between measurements.

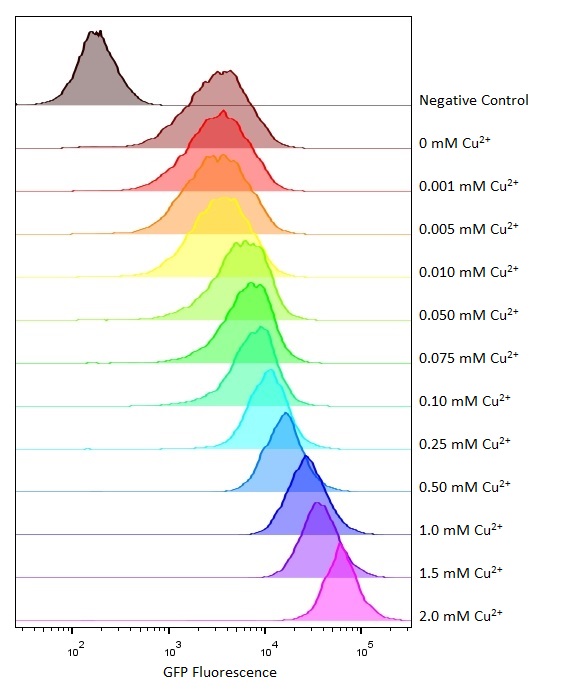

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry is a technique whereby cells are passed individually into the path of a beam of light. The frequency range of incident light can be adjusted to allow excitation of specific fluorophores in the sample of cells. Downstream detectors can measure fluorescent emission, and this data can be used to quantify the amount of fluorophore in each cell.

To ensure comparability of experiments, all cells were grown for 3-4hrs (until entrance into the exponential growth phase) at 37°C and 225rpm shaking in the presence of the inducer before measurement. This allowed adequate time for activation of expression by the promotor systems. The negative control used in all cases were MG1655 bacteria containing an empty shipping plasmid. As these did not contain any fluorescent molecules, this population could be used to set the negative “gate” (i.e. the background fluorescence of the bacterial cells). Although the experiments were tedious as every sample had to be measured manually, the results were of remarkably high quality, were clearly interpretable, and fit very well with the other experimental data.

Microscopy

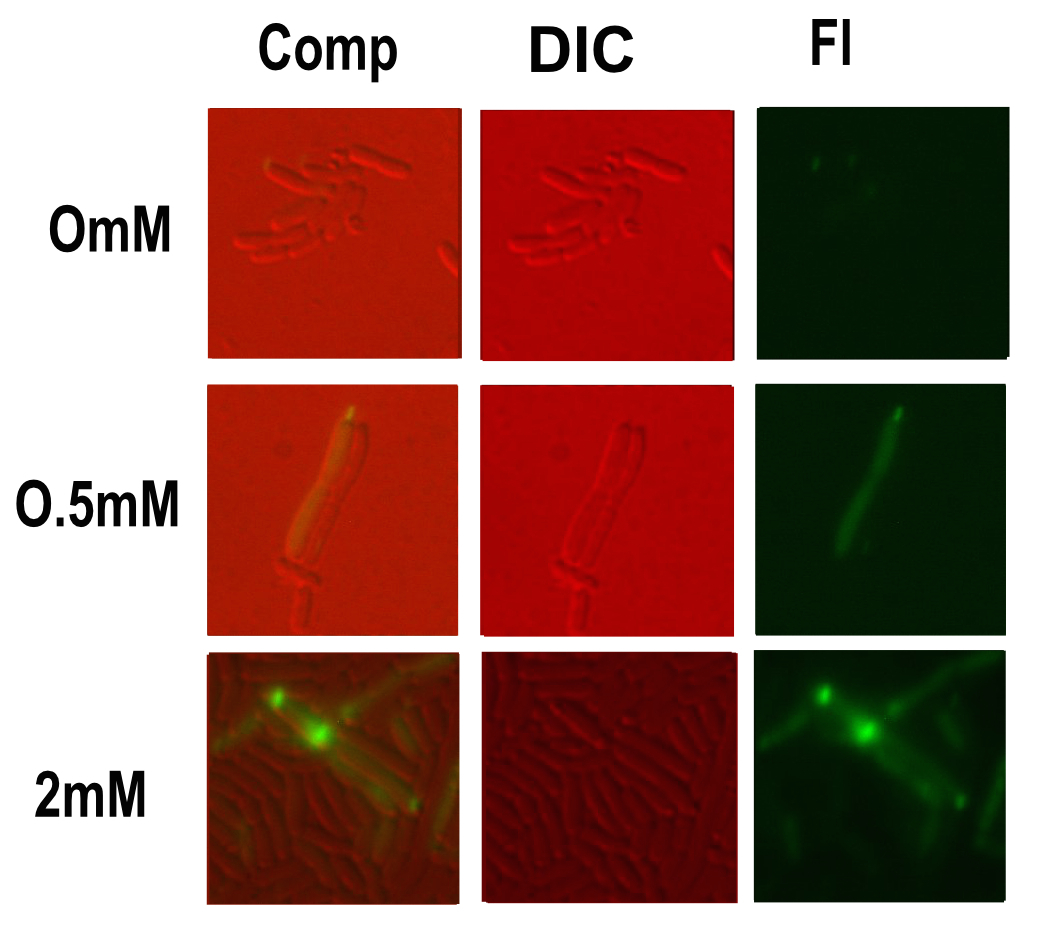

Microscopy was done in order to visually confirm the plate reader and flow cytometer experiments.

The experiment started with 5ml overnight cultures containing the appropriate antibiotic. Then in the morning 100μl of each colony was pipetted into 5ml of fresh LB with antibiotic and a range of copper concentrations and grown till the OD reached 0.4-0.6.

A flask of 1% agarose made with MilliQ was melted. 200μl of this was placed on a slide between two coverslips, flattened to get a nice smooth surface where the bacteria are immobile. 20μl of the culture are then added. The slide was then be viewed under a fluorescence microscope.

After finding the correct focal plane the slide was moved to find as many cells as possible to image. After focusing again an image of the DIC and fluorescence channels was obtained.

Likely due to the expression problems of the Csp1 chelator in E. coli, it responded worse than the similar part with our MymTsfGFP fusion protein (https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1980012)

Conclusions

We designed this part to act as a positive feedback system that would increase the sensitivity to copper. Instead, it appears to act as negative feedback system dampening the response to copper. This also seems to have reduced the variation between cells as shown by the flow cytometer data. Under some circumstances this could be a useful feature being able to keep the chelator concentration more similar and predictable over a wider concentration range but this part and behaviour was not deemed to be useful over the physiological copper concentrations we were interested in.

References

(1) Danya J. Martell, Chandra P. Joshi, Ahmed Gaballa, Ace George Santiago, Tai-Yen Chen, Won Jung, John D. Helmann, and Peng Chen (2015) “Metalloregulator CueR biases RNA polymerase’s kinetic sampling of dead-end or open complex to repress or activate transcription” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 Nov 3; 112(44): 13467–13472.

(2) Yamamoto K, Ishihama A. (2005) “Transcriptional response of Escherichia coli to external copper.” Mol Microbiol. 2005 Apr;56(1):215-27.

Author: Andreas Hadjicharalambous

//cds/reporter/gfp

//cds/transcriptionalregulator

//function/reporter/fluorescence

//function/sensor/metal

//promoter

| None |