Part:BBa_K1420002

merB, Organomercurial Lyase from Serratia marcescens

Overview

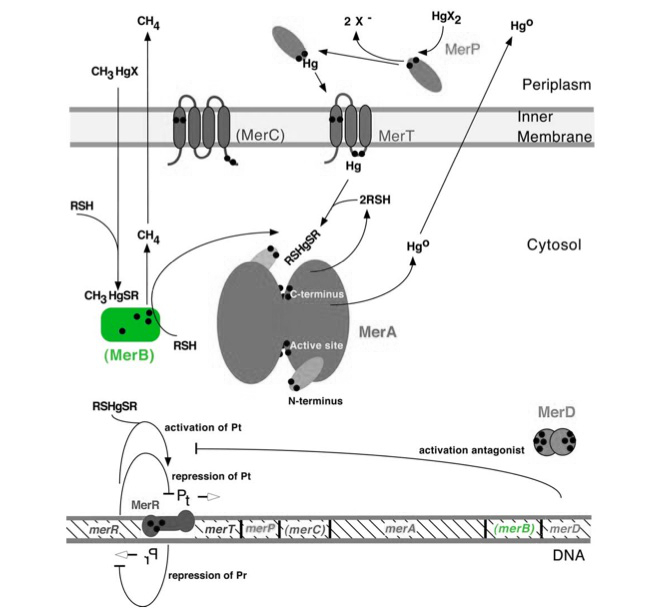

The carbon-mercury bond lyase encoding genemerB (0.6Kb) encodes MerB. MerB and gene merB are highlighted in green in Figure 1. The lower part of the Figure 1 shows the arrangement of mer genes in the operon, and merB is located downstream of the transport and reductase genes, merP, merT and merA, respectively.

Figure 1. Model of carbon-mercury lyase operon. The symbol • indicates a cysteine residue. RSH indicates cytosolic thiol redox buffers such as glutathione. Figure 1 shows the interactions of MerB, in green, with mercury compounds and other gene products of mer operon. (Figure adapted from "Bacterial mercury resistance from atoms to ecosystems". Reference: T. Barkay et al. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 27 (2003) 355-384.)

Molecular Function

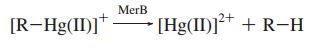

The merB gene is often found immediately downstream of merA, and is essential for the detoxification and bioremediation of organic toxic mercury compounds in congruence with merA. The merB protein is a lyase that catalyzes the breaking of carbon-mercury bonds through protonolysis of toxic mercury compounds, such as methylmercury (Scheme 1). This produces the less toxic and less mobile Hg2+ which is then completely volatilized to Hg0 when acted upon the enzyme merA.

Scheme 1. MerB Catalyzed Reaction (R= alkyl, aryl)

Structure and Mechanism

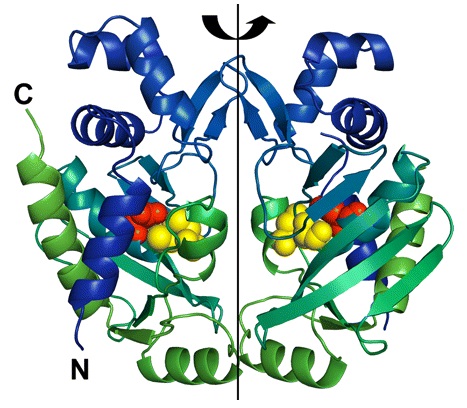

Enzyme MerB forms a dimer by a 2-fold pseudosymmetry around the depicted rotation axis in Figure 1. The two subunits are color coded from blue to green distinguishing the amino-terminal end of the protein from the carboxy-terminal, respectively. Active site residues are color coded as well using van der Waals sphere representation: residues Cys-96 and Cys-159 are in yellow, and residue Asp-99 is in red. The structure of mercury-bound MerB and free MerB is extremely similar with the exception of the mercury ion. The mercury is bound to MerB by two sulfurs from the Cys-96 and Cys-159. An oxygen from a water molecule is also involved, binding to the mercury atom. On the other hand, the active site residues for the free MerB are completely inaccessible.

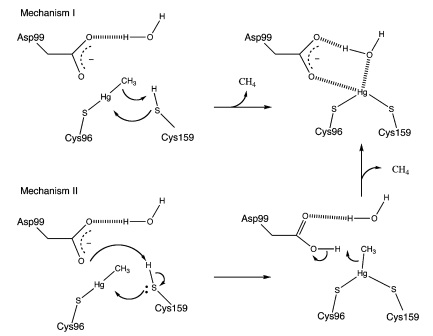

MerB can catalyze the protonolysis of carbon mercury bonds for a number of organomercurials, accelerating the rate of this reaction up to 107 times the rate of spontaneous abiotic decay. Two proposed mechanisms for how this is accomplished is displayed in Figure 2. Both mechanisms assume that the methylmercury substrate forms an initial bond with Cys96 and that the Cys159 site is protonated. In Mechanism 1, Cys159 protonates the methyl carbon and forms a covalent bond with Hg(II). In Mechanism 2 however, Cys159 donates a proton to Asp99 before forming a bond with Hg(II). Asp99 is then responsible for protonating the methyl group.

Figure 2. Structure of MerB enzyme. MerB is a dimer with 2-fold pseudosymmetry. The amino-terminal and carboxy-terminal are color coded blue and green, respectively. In addition, the active site residues Cys-96 and Cys-159 are in yellow, and residue Asp-99 is in red. (Figure adapted from "Enzyme Catalysis and Regulation: Crystal Structures of the Organomercurial Lyase MerB in Its Free and Mercury-bound Forms: Insights into the Mechanism of Methylmercury Degredation". Reference: J. Lafrance-Vanasse et al (2009). The Journal of Biological Chemistry 284: 938-944.)

Figure 3. Proposed mechanisms of MerB catalysis for the Hg-C protonolysis reaction. Both of these proposed mechanisms display how methyl group of methylmercury is protonated, producing Hg(II). Mechanism 2 differs from Mechanism 1 by utilizing Asp99 for protonation of the methyl group with the hydrogen attached to the sulfur from Cys159.

merB Experimental Results

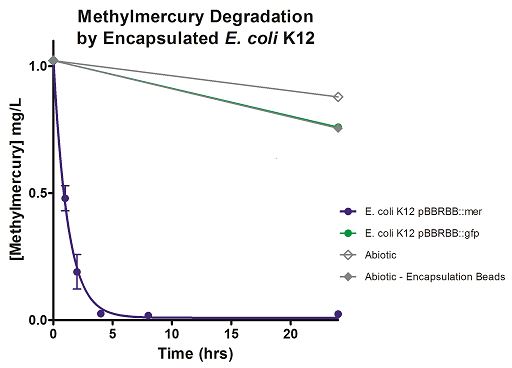

The function of merB in the mer operon for the conversion of methylmercury to Hg(II) was tested in E. coli K12 strain cells which is depicted in Figure 3. For line that represents the bioremediation of methylmercury in abiotic environments, methylmercury is converted at an extremely low rate. The rate of methylmercury conversion when encapsulation beads were involved matched the rate corresponding to E. coli K12 strain containing the pBBRBB::gfp control plasmid, which is still seen to take a considerable amount of time (well over 25 hours). The E. coli K12 containing the pBBRBB::mer, however, is seen to remove methylmercury from the system almost completely after only 8 hours.

Figure 4. Monitoring the levels of mer operon methylmercury bioremediation. The graph displays that abiotic, abiotic with encapsulation beads, and the E. coli K12 strain containing the pBBRBB::gfp control bioremediate methylmercury from the environment at a much slower rate than the E. coli K12 containing the pBBRBB::mer, which can remove methylmercury from the system almost completely in approximately 8 hours.

References

Sequence and Features

- 10COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[10]

- 12COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[12]

- 21COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[21]

- 23COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[23]

- 25INCOMPATIBLE WITH RFC[25]Illegal NgoMIV site found at 415

- 1000COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[1000]

//cds

| None |