Difference between revisions of "Part:BBa K1172501"

(→Overview) |

|||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

| − | *<p align="justify">Upon expression of the outer membrane porin protein OprF, the morphological and physicochemical characteristics of the ''E. coli'' surface were analyzed. [[Team:Bielefeld-Germany/Labjournal/Molecular#Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) | SDS-PAGE]] combined with [[Team:Bielefeld-Germany/Labjournal/Molecular#MALDI-TOF|MALDI-TOF MS/MS]], different membrane permeability assays ( | + | *<p align="justify">Upon expression of the outer membrane porin protein OprF, the morphological and physicochemical characteristics of the ''E. coli'' surface were analyzed. [[Team:Bielefeld-Germany/Labjournal/Molecular#Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) | SDS-PAGE]] combined with [[Team:Bielefeld-Germany/Labjournal/Molecular#MALDI-TOF|MALDI-TOF MS/MS]], different membrane permeability assays ([http://2013.igem.org/Team:Bielefeld-Germany/Labjournal/Molecular#NPN_membrane_permeability_assay NPN] and [[Team:Bielefeld-Germany/Labjournal/Molecular#ONPG membrane permeability assay | ONPG]]), a [[Team:Bielefeld-Germany/Labjournal/Molecular#Hexadecan Assay|hydrophobicity assay]] and [[Team:Bielefeld-Germany/Labjournal/Molecular#Preparing samples for Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) analysis of the OM of cells|Atomic Force Microscopy]] (AFM) characterize the OprF BioBrick <bbpart>BBa_K1172501</bbpart>.</p> |

| − | + | ||

===SDS-PAGE and MALDI-TOF=== | ===SDS-PAGE and MALDI-TOF=== | ||

Revision as of 21:44, 4 October 2013

Outer membrane porin OprF from Pseudomonas fluorescens

By heterologous expression of the pore-forming transmembrane-protein (or porine) OprF from Pseudomona fluorescens a further optimization of the E. coli membrane will be achieved. E. coli possesses several own porines, for example OmpF and OmpC. But these naturally occurring porines are only permeable for molecules smaller than 600 Da, which decreases the range of usable mediators significantly. Opposed to that, porine OprF from P. fluorescence forms one of the biggest known pores in the outer bacterial membrane with a permeability of up to 3000 Da, thus improving the electron shuttle mediated extracellular electron transfer (ETT) and enabling the usage of alternative mediators such as riboflavin (vitamine B2).

Sequence and Features

- 10COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[10]

- 12COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[12]

- 21INCOMPATIBLE WITH RFC[21]Illegal BglII site found at 764

- 23COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[23]

- 25INCOMPATIBLE WITH RFC[25]Illegal NgoMIV site found at 1156

- 1000INCOMPATIBLE WITH RFC[1000]Illegal BsaI site found at 677

Results

Overview

Upon expression of the outer membrane porin protein OprF, the morphological and physicochemical characteristics of the E. coli surface were analyzed. SDS-PAGE combined with MALDI-TOF MS/MS, different membrane permeability assays ([http://2013.igem.org/Team:Bielefeld-Germany/Labjournal/Molecular#NPN_membrane_permeability_assay NPN] and ONPG), a hydrophobicity assay and Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) characterize the OprF BioBrick BBa_K1172501.

SDS-PAGE and MALDI-TOF

OprF was detected in an SDS-PAGE with a broad overexpression band. Protein isolation of the outer membrane porin OprF by release of periplasmic protein fraction from E. coli via cold osmotic shock using Cell fractionating buffer 2.3 was successful.

Figure 2: SDS-PAGE with [http://www.thermoscientific.com/ecomm/servlet/productsdetail_11152___13576050_-1 Prestained Protein Ladder from Thermo Scientific] as marker. Comparison of protein expression between Escherichia coli KRX wild type and Escherichia coli KRX with BBa_K1172502, BBa_K1172503 and BBa_K1172507 after periplasmic protein fractioning with Cell fractionating buffer 2.3. The band used for the MALDI-TOF MS/MS is marked with an arrow.

The SDS-PAGE shows a significantly higher protein concentration in extracts from E.coli expressing OprF from a T7 promoter (BBa_K1172502). This is most likely caused by the higher membrane permeability (shown with NPN and ONPG uptake assay), allowing an increased release of membrane proteins by 0.2 % SDS. Nevertheless, a strong overexpression band can be observed at the expected OprF size of about 36 kDa for BBa_K1172502, which is equated with a strong expression and overproduction of OprF.

Furthermore we were able to identify the overexpressed outer membrane porin (Figure. 2) with MALDI-TOF MS/MS.

Tryptic digest of the gel band thought to represent OprF and analysis with MALDI-TOF confirmed the outer membrane porin with a Mascot Score of 222 against the bacteria database.

Hydrophobicity (Hexadecane) - Assay

The heterologous expression of the outer membrane porin OprF will enhance the hydrophobicity of cell membrane. The outward-facing side groups on each of the β-strands of the OprF monomer are hydrophobic. Therefore a positive expression should be visible by an increase in hydrophobicity. The Hexadecane-Hydrophobicity-Assay is based on different affinities to hexadecane of dissimilar cell-types according to their cell surface. Hydrophobicity can be observed by specific changes in OD600 of the aqueous phase.

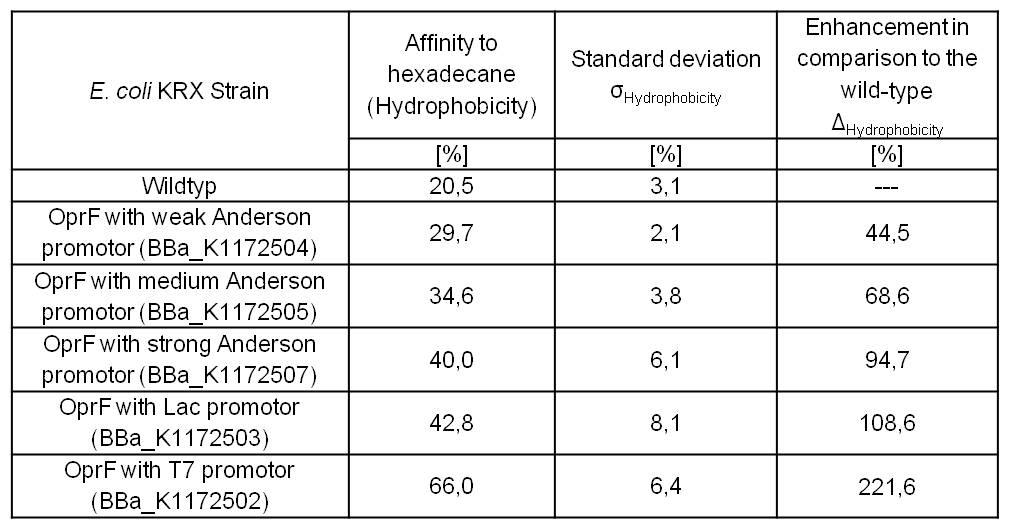

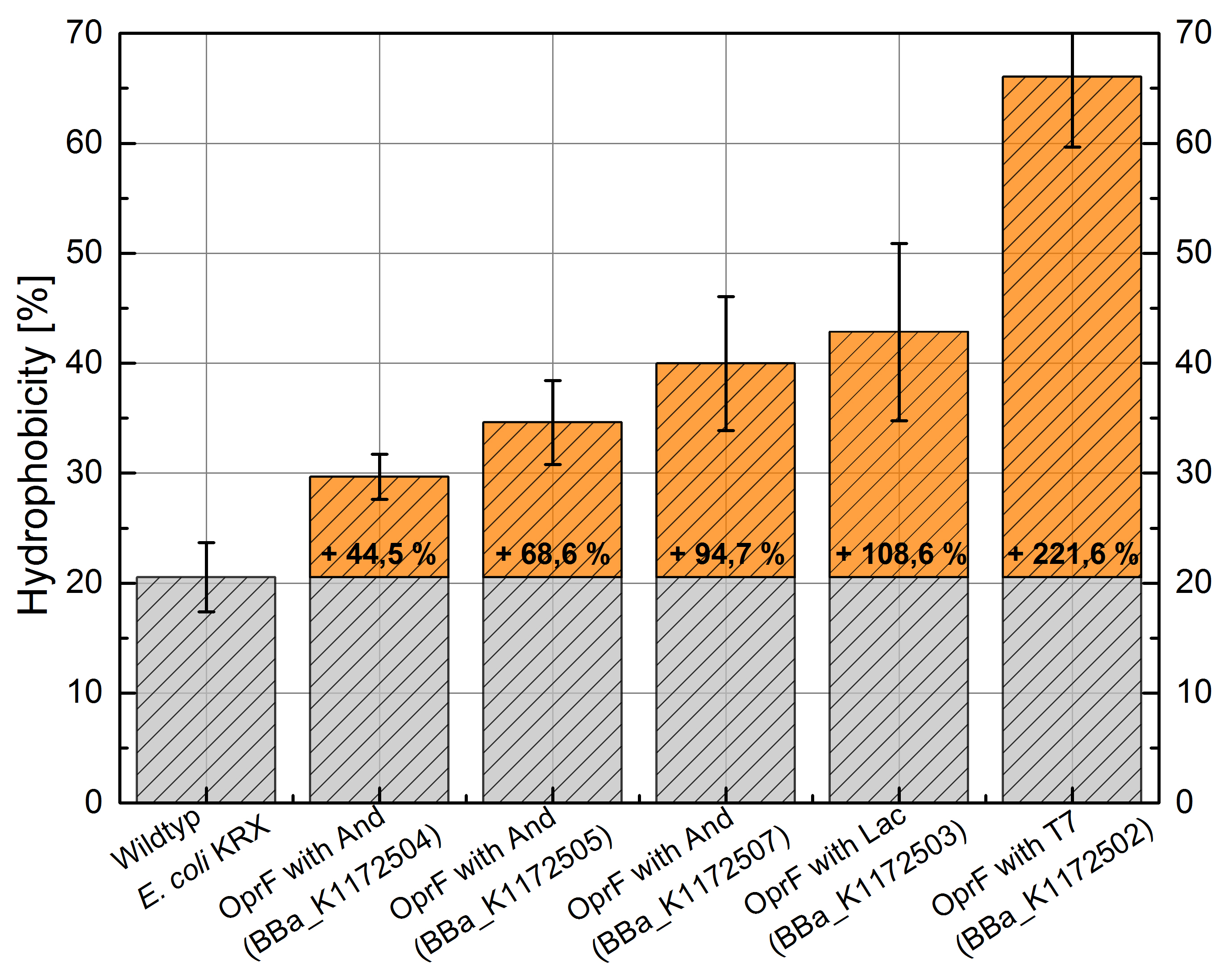

An increasing hydrophobicity of cell membrane changes the physicochemical properties of the cell. This could effect for example the cell-electrode interaction. Therefore, we investigated the cellular surface characteristic by comparing Escherichia coli KRX wild type with Escherichia coli KRX with BBa_K1172502, BBa_K1172503, BBa_K1172504, BBa_K1172505 and BBa_K1172507 (Table 2 and Figure 3).

The OprF strain shows an increasing affinity to hexadecane with increasing promoter strength in comparison to the wild type. Cells in which OprF was expressed from the T7 promoter (BBa_K1172502) showed the maximal hydrophobicity, which was three times higher than the affinity to hexadecane of the wild type.

Table 2: Results of the Hexadecane-Hydrophobicity-Assay. Comparison of hydrophobicity between Escherichia coli KRX wild type and Escherichia coli KRX with BBa_K1172502, BBa_K1172503, BBa_K1172504, BBa_K1172505 and BBa_K1172507. Affinity to hexadecane (hydrophobicity) with standard deviation and enhancement in comparison to the wild type is shown. Two biological and at least three technical replicates were analyzed.

Figure 3: Results of the Hexadecane-Hydrophobicity-Assay. Comparison of hydrophobicity between Escherichia coli KRX wild type and Escherichia coli KRX with BBa_K1172502, BBa_K1172503, BBa_K1172504, BBa_K1172505 and BBa_K1172507. Affinity to hexadecane (hydrophobicity) with standard deviation and enhancement in comparison to the wild type is shown. Two biological and at least three technical replicates were analyzed.

The enhanced hydrophobicity of OprF-strains indicates a successful expression of the outer membrane porin in Escherichia coli. Such an increased hydrophobicity on the outer membrane caused by the expression of OprF will lead to an increase in the cellular adhesion to the surface of the carbon anode and an enhancement of direct electron transfer from Escherichia coli to the electrode.

Membrane permeability assays

NPN uptake assay

Besides testing the outer membrane hydrophobicity for physicochemical characterization of the E. coli surface, we measured the membrane permeability by fluorescence-based NPN (N-Phenyl-1-naphthylamine) uptake assay for outer membrane morphology characterization (Helander and Mattila-Sandholm, 2000).

NPN is a suitable chemical for measuring the membrane permeability of cells. An increasing NPN fluorescence intensity indicates an enhanced NPN uptake through the outer membrane and enhanced membrane permeability (Loh et al., 1984).

Figure 4 shows a higher fluorescence emission and hence higher membrane permeability with increasing promoter strength for OprF strains in comparison to Escherichia coli KRX wild type.

Figure 4: Results of the NPN-uptake-assay. Comparison of fluorescence emission between Escherichia coli KRX wild type and Escherichia coli KRX with BBa_K1172502, BBa_K1172503, BBa_K1172504, BBa_K1172505 and BBa_K1172507. Excitation at 355 nm with fluorescence emission scan from 320 to 390 nm wavelength and with standard deviation. Two biological and at least three technical replicates were analyzed.

Escherichia coli with heterologous expression of the outer membrane porin OprF shows more efficient NPN uptake than the Escherichia coli KRX wild type, suggesting an increased membrane permeability with increasing promoter strength. E. coli with oprF under T7 promoter control (BBa_K1172502) shows the maximal membrane permeability with 100% enhanced permeability in comparison to E. coli KRX wild type. The weak Anderson promoters seems unsuitable for heterologous expression.

ONPG assay

Another way of characterizing the outer cell membrane can be achieved with an fluorescence-based ONPG assay. This assay measures the membrane permeability by whole-cell lactase enzyme activity (Zhou et al., 2010).

Electron shuttle-mediated electron transfer (EET) determines the transport efficiency of electron shuttles across the cell membrane. With the NPN uptake assay we were able to quantify the transport efficiency of chemical molecules across the cell membrane. In contrast, the ONPG assay (whole-cell β-lactase enzyme activity assay) measures the diffusion of the ONPG and its hydrolytic product across the cell membrane, which quantifies not only uptake, but also the hydrolytic product release. With the ONPG assay we are able to observe diffusion processes in and out of the cell membrane.

Due to the fact that heterologous expression of OprF in Escherichia coli should not have an impact on the expression of β-lactase, we can assume that the β-lactase activity of E. coli KRX wild type and E. coli KRX with OprF expression plasmid is identical. All in all, the ONPG assay provides significantly more information than the NPN uptake assay.

Figure 5: Results of the ONPG-uptake-assay. Comparison of ONPG hydrolysis between Escherichia coli KRX wild type and Escherichia coli KRX with BBa_K1172502, BBa_K1172503, BBa_K1172504, BBa_K1172505 and BBa_K1172507. Absorbance at 405 nm wavelength with standard deviation is shown. Two biological and at least three technical replicates were analyzed.

The ONPG hydrolysis rate by β-lactase is much higher for E. coli KRX containing OprF plasmids in contrast to E. coli KRX wild type. Whereas we could only observe a minimal hydrolysis activity in the wild type, E. coli KRX, carrying OprF expression plasmids, shows a much faster ONPG hydrolysis rate with increasing promoter strength and a maximal rate for E. coli KRX with T7 promoter (BBa_K1172502), which is 30 times higher than wild type hydrolysis rate.

In summary, we could prove that the heterologous expression of OprF from Pseudomonas fluorescens in Escherichia coli significantly improves the membrane permeability. The NPN and ONPG assay show correlating results. Outer membrane permeability of E. coli is enhanced with increasing promoter strength for OprF expression. The wild type shows only a weak uptake rate of chemical molecules (NPN) and no product release as quantified with ONPG assay. Therefore, the E. coli wild type is not well suitable for a usage in the MFC using mediators. In contrast, membrane optimized Escherichia coli with OprF shows increased diffusion across the cellular membrane, indicating a possible optimization of electron shuttle-mediated electron transfer (EET) to the anode and increasing current production.

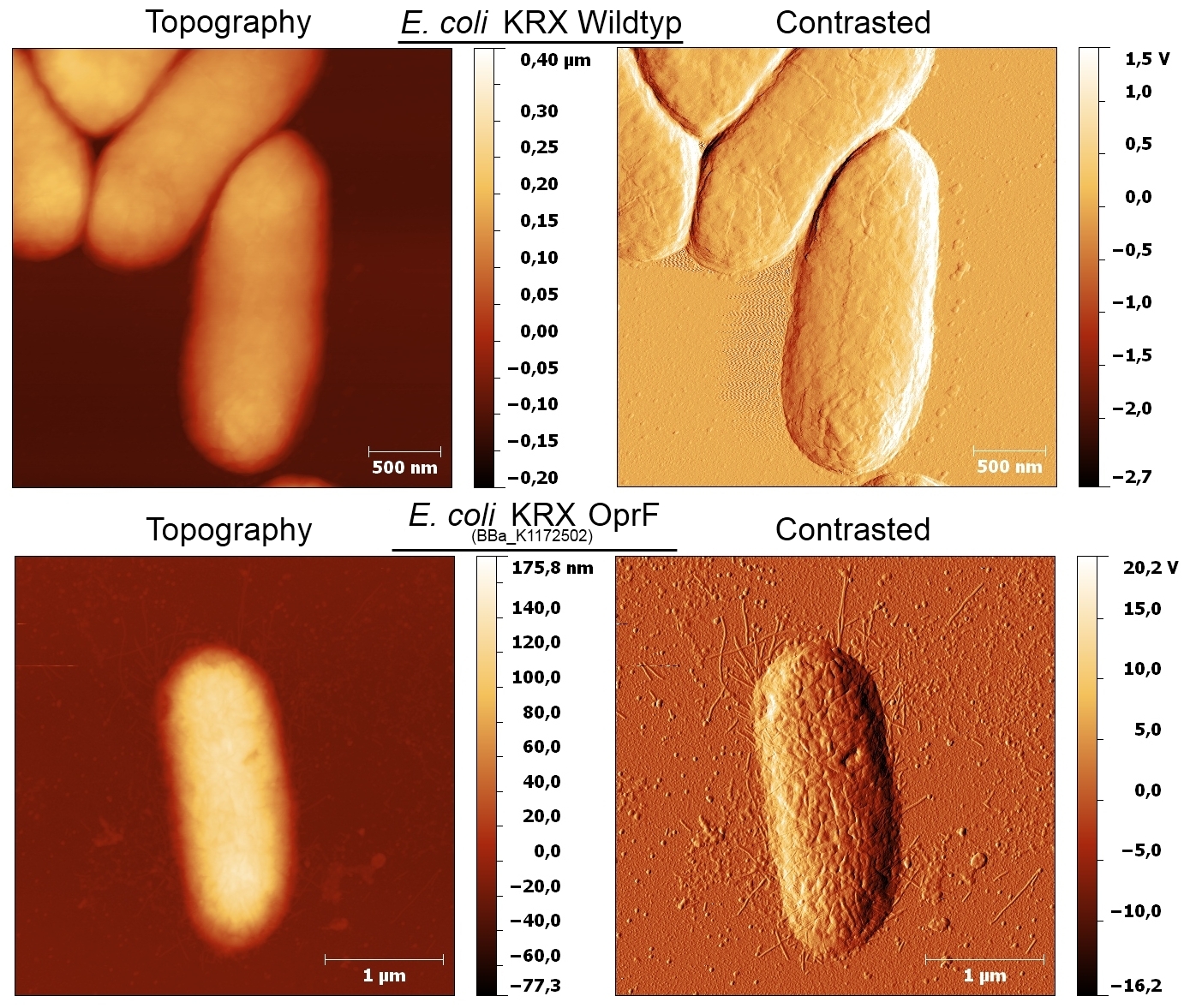

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

In addition to the morphological and physicochemical characterization of the Escherichia coli outer membrane, we wanted to visualize the surface. The technique of choice for this is Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM). After cell preparation we were able to get AFM pictures of the E. coli surface with the help of the working group of [http://www.physik.uni-bielefeld.de/biophysik Prof. Dr. Dario Anselmetti], with special help from [http://www.physik.uni-bielefeld.de/biophysik/mitarbeiter/walhorn.html Dr. Volker Walhorn]. Thank you very much for your help!

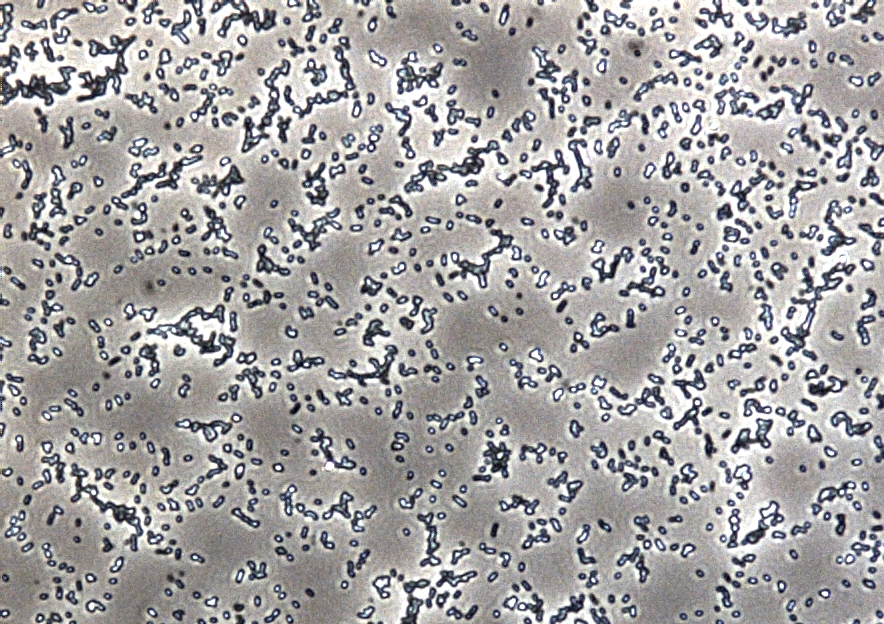

Figure 6: Light microscopy of AFM layer after cell preparation of Escherichia coli KRX wild type.

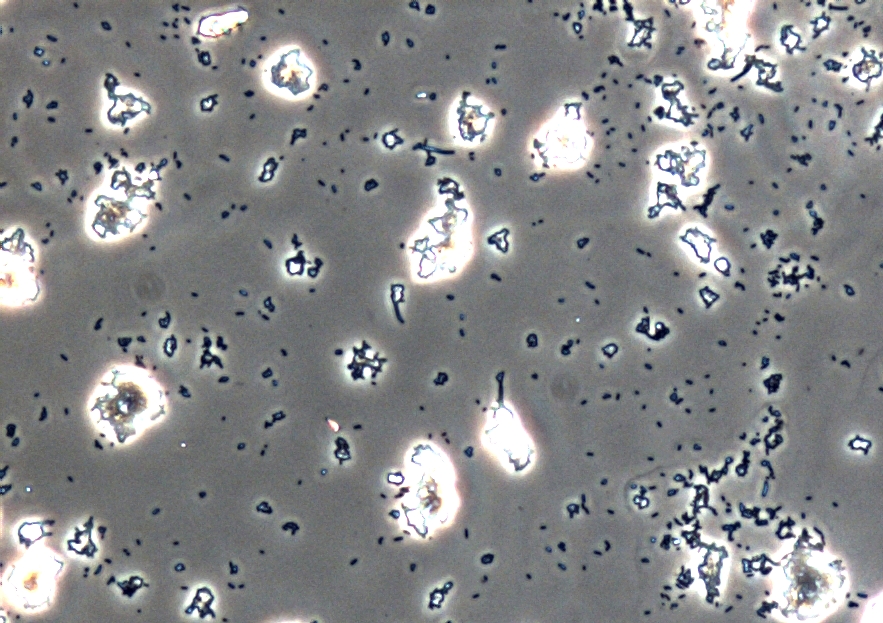

Figure 7: Light microscopy of AFM layer after cell preparation of Escherichia coli carrying oprF under the control of T7 promoter (BBa_K1172502). Enhanced cell clustering, caused by higher hydrophobicity, can be observed.

Microscopy of the AFM glass layer after cell preparation, before AFM measurement, shows the different cell properties. Number of cells as well as magnification scale are the same. Escherichia coli KRX expressing OprF from a T7 promoter (BBa_K1172502) presents a clustering of cells, whereas the wild type forms a monolayer. Thus, the increased hydrophobicity of the cell surface is already visible even with an ordinary light microscope.

AFM was carried out using the [http://www.bruker.com/de/products/surface-analysis/atomic-force-microscopy/multimode-8/overview.html MultiMode® 8 AFM from Bruker]. The measurements were performed on air with ‘Tapping Mode’ and in water with ‘Peak Force Mode’.

Figure 8: AFM images of the cell surface for Escherichia coli KRX wild type and Escherichia coli KRX with heterologous expression of porin OprF (BBa_K1172502). Images are shown in Topography and Contrast mode.

Based on the AFM images, Escherichia coli KRX with OprF and T7 promoter (BBa_K1172502) shows a slightly rougher cell surface morphology in contrast to Escherichia coli KRX wild type. Outer membrane porin OprF from Pseudomonas fluorescens usually forms trimer complexes on the membrane, which leads to enhanced roughness of the cell surface. (Yong et al., 2013)

The heterologous expression of the porin OprF causes a slightly rougher membrane, the morphology and thus the viability of Escherichia coli is preserved to the greatest possible extent.

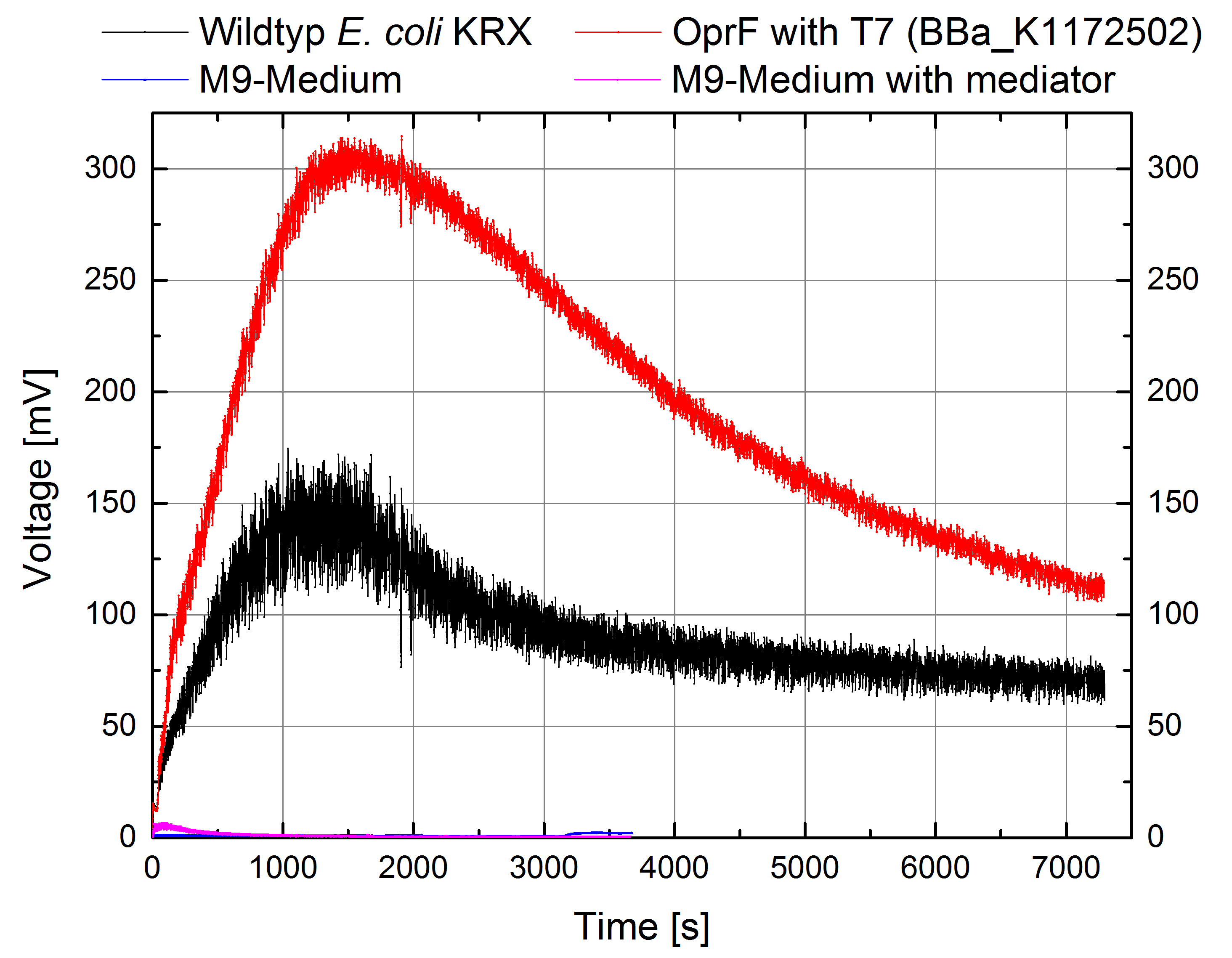

Microbial Fuel Cell Measurement

All results so far indicated the potential for an increase in energy production. This assumption was confirmed by cultivation of Escherichia coli KRX with OprF (BBa_K1172502) in comparison to Escherichia coli KRX wild type in the Microbial Fuel Cell.

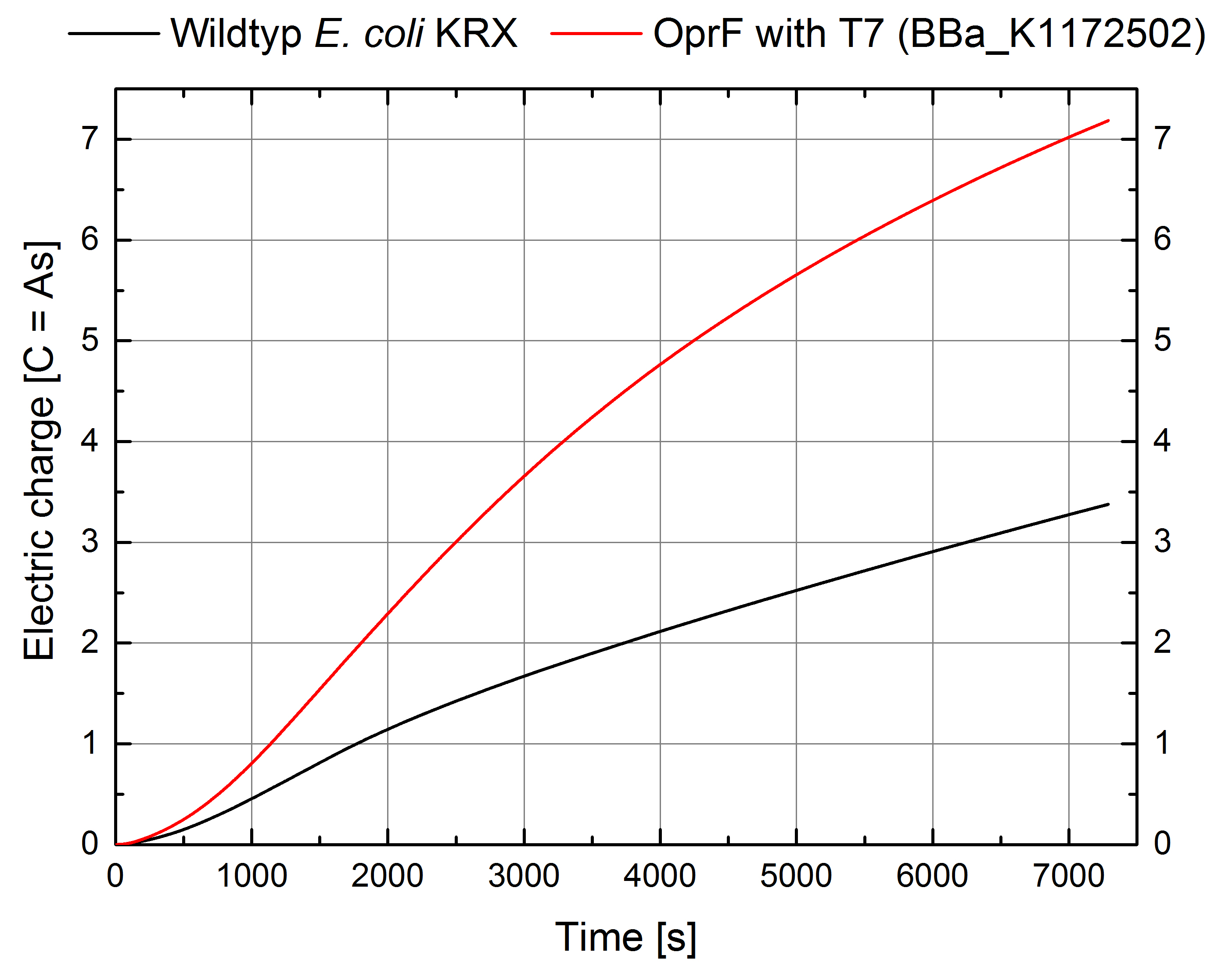

Indeed, the extracellular electron transfer mediated by electron shuttles is improved in the OprF expressing strain resulting in an increased bioelectricity output (Figure 10, 11 and 12).

Figure 10: Microbial Fuel Cell results from cultivation of Escherichia coli KRX with OprF (BBa_K1172502) in contrast to Escherichia coli KRX wild type. Voltage curve from Escherichia coli KRX wild type, Escherichia coli KRX expressing OprF (BBa_K1172502), M9 medium with Methylene Blue as mediator and M9 medium without mediator is shown over time and over a resistance of 200 Ω.

Figure 11: Microbial Fuel Cell results from cultivation of Escherichia coli KRX expressing OprF (BBa_K1172502) in contrast to Escherichia coli KRX wild type. Electric charge curve from Escherichia coli KRX wild type and Escherichia coli KRX carrying OprF (BBa_K1172502). M9 medium was used with mediator Methylene Blue and with measurement over a resistance of 200 Ω.

Figure 12: Microbial Fuel Cell results from cultivation of Escherichia coli KRX expressing OprF (BBa_K1172502) in contrast to Escherichia coli KRX wild type. Electric power curve from Escherichia coli KRX wild type and Escherichia coli KRX carrying OprF (BBa_K1172502). M9 medium was used with mediator Methylene Blue and with measurement over a resistance of 200 Ω.

Escherichia coli KRX with OprF (BBa_K1172502) shows 108 % higher maximal voltage than Escherichia coli KRX wild type with a maximum of 308 mV. Over the whole cultivation the voltage was improved by about 100 %. Tests using M9-medium with and without mediator Methylene Blue show no voltage, indicating that bioelectricity generation is solely due to the bacteria.

The calculation of the electric charge confirms the described results. Electric charge is equivalent to the number of transported electrons and is enhanced by 111 % for Escherichia coli KRX with OprF (BBa_K1172502). The maximal electric charge of 7,2 C demonstrates that heterologous expression of outer membrane porin OprF enhances extracellular electron transfer dramatically. High membrane permeability is crucial for efficient mediator transport across the membrane and therefore for high bioelectricity generation.

Finally, the calculated power curve shows 239 % enhanced electric power for Escherichia coli KRX carrying OprF (BBa_K1172502) with a maximal electric energy transfer rate of 475 μW.

Conclusion

Cell membranes are protective layers, which are crucial for physiology of the bacteria. In consideration of the Microbial Fuel Cell, the cell membrane is also a barrier which decreases mediator and thus electron exchange between bacteria and anode. With heterologous expression of the outer membrane porin OprF from Pseudomonas fluorescens in Escherichia coli we were able to enhance membrane permeability. With this optimized cell membrane surface we generate an efficient electron shuttle-mediated EET with decreased limitation of EET by membrane barrier. In contrast to a perforation of the membrane with chemicals, cell viability is maintained with OprF expression (Liu et al., 2012). Beside improvement of EET, enhanced hydrophobicity shows optimized cell adhesion to the anode for biofilm formation and direct electron transfer.

The heterologous expression of OprF is a genetic strategy to optimize electron shuttle-mediated electron transfer as well as electricity generation in Microbial Fuel Cells. The most suitable and efficient OprF device for Escherichia coli is a combination with the rhamnose inducible T7 promoter (BBa_K1172502).

References

Hancock REW, Brinkman FSL (2002) Function of Pseudomonas porins in uptake and efflux. [http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.micro.56.012302.160310| Annu Rev Microbiol (56):17–38].

Helander IM, Mattila-Sandholm T (2000) Permeability barrier of the gramnegative bacterial outer membrane with special reference to nisin. [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S016816050000307X|Int J Food Microbiol 60: 153–161].

Liu J, Qiao Y, Lu ZS, Song H, Li CM (2012) Enhance electron transfer and performance of microbial fuel cells by perforating the cell membrane. [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1388248111004723|Electrochem Commun 15: 50–53].

Logan BE (2009) Exoelectrogenic bacteria that power microbial fuel cells. [http://www.nature.com/nrmicro/journal/v7/n5/full/nrmicro2113.html| Nat Rev Microbiol (7): 375–381].

Loh B, Grant C, Hancock REW (1984) Use of the fluorescent-probe 1-Nphenylnaphthylamine to study the interactions of aminoglycoside antibiotics with the outer-membrane of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. [http://aac.asm.org/content/26/4/546.short|Antimicrob Agents Chemother 26: 546–551].

Yong YC, Yu YY, Yang Y, Liu J, Wang JY, Song H (2013) Enhancement of Extracellular Electron Transfer and Bioelectricity Output by Synthetic Porin. [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/bit.24732/full|Biotechnology and Bioengineering 110 (2): 408-416].

Zhou ZX, Wei DF, Guan Y, Zheng AN, Zhong JJ (2010) Damage of Escherichia coli membrane by bactericidal agent polyhexamethylene guanidine hydrochloride: Micrographic evidences. [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04482.x/full|J Appl Microbiol 108: 898–907].