Difference between revisions of "Part:BBa K525223"

(→Identification and localisation) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

__NOTOC__ | __NOTOC__ | ||

<partinfo>BBa_K525223 short</partinfo> | <partinfo>BBa_K525223 short</partinfo> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Bielefeld-Germany2011-S-Layer-Geometrien.jpg|300px|right]] | ||

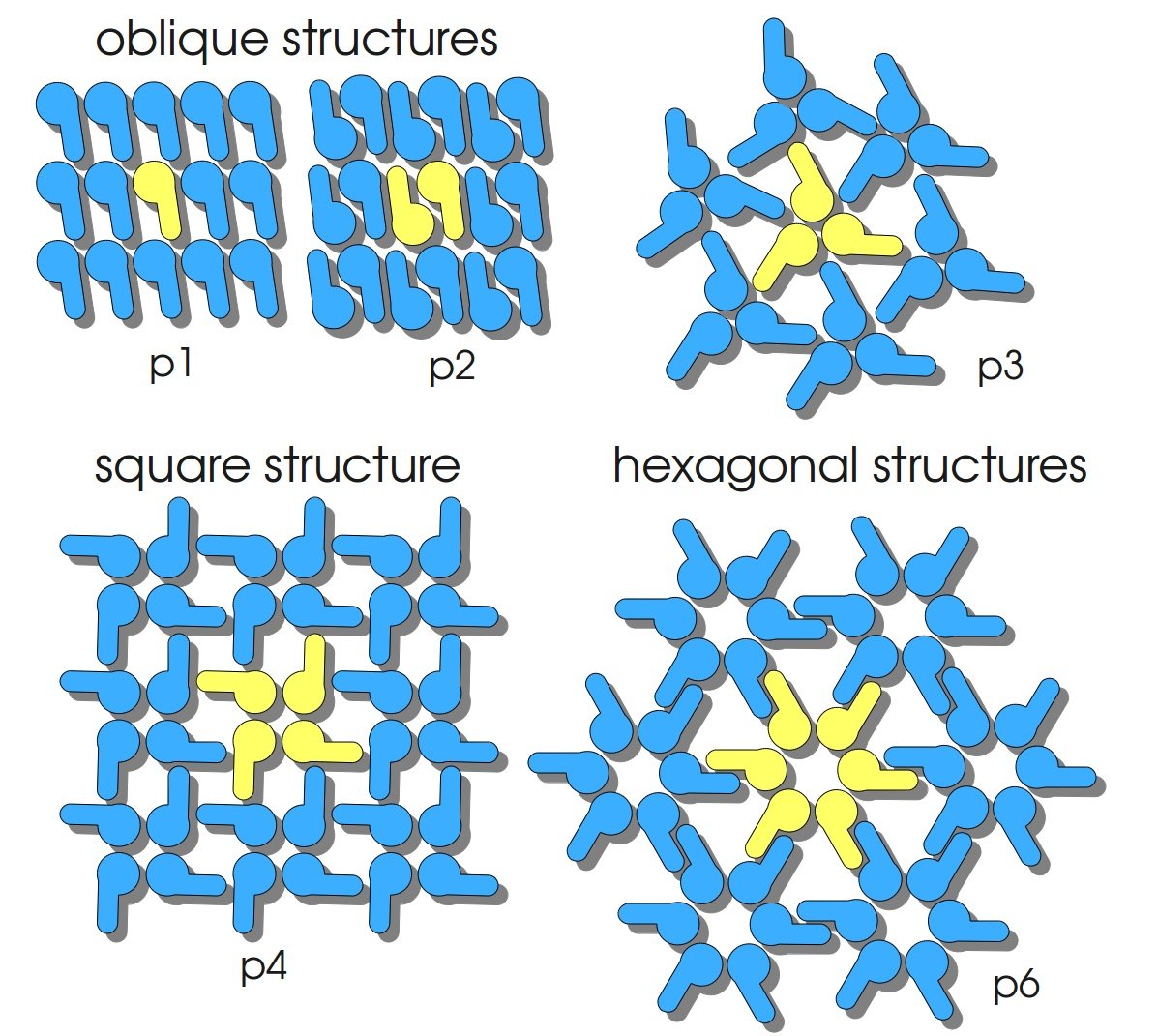

S-layers (crystalline bacterial surface layer) are crystal-like layers consisting of multiple protein monomers and can be found in various (archae-)bacteria. They constitute the outermost part of the cell wall. Especially their ability for self-assembly into distinct geometries is of scientific interest. At phase boundaries, in solutions and on a variety of surfaces they form different lattice structures. The geometry and arrangement is determined by the C-terminal self assembly-domain, which is specific for each S-layer protein. The most common lattice geometries are oblique, square and hexagonal. By modifying the characteristics of the S-layer through combination with functional groups and protein domains as well as their defined position and orientation to eachother (determined by the S-layer geometry) it is possible to realize various practical applications ([http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00573.x/full Sleytr ''et al.'', 2007]). | S-layers (crystalline bacterial surface layer) are crystal-like layers consisting of multiple protein monomers and can be found in various (archae-)bacteria. They constitute the outermost part of the cell wall. Especially their ability for self-assembly into distinct geometries is of scientific interest. At phase boundaries, in solutions and on a variety of surfaces they form different lattice structures. The geometry and arrangement is determined by the C-terminal self assembly-domain, which is specific for each S-layer protein. The most common lattice geometries are oblique, square and hexagonal. By modifying the characteristics of the S-layer through combination with functional groups and protein domains as well as their defined position and orientation to eachother (determined by the S-layer geometry) it is possible to realize various practical applications ([http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00573.x/full Sleytr ''et al.'', 2007]). | ||

Revision as of 22:42, 21 September 2011

S-layer cspB from Corynebacterium halotolerans with lipid anchor, PT7 and RBS

S-layers (crystalline bacterial surface layer) are crystal-like layers consisting of multiple protein monomers and can be found in various (archae-)bacteria. They constitute the outermost part of the cell wall. Especially their ability for self-assembly into distinct geometries is of scientific interest. At phase boundaries, in solutions and on a variety of surfaces they form different lattice structures. The geometry and arrangement is determined by the C-terminal self assembly-domain, which is specific for each S-layer protein. The most common lattice geometries are oblique, square and hexagonal. By modifying the characteristics of the S-layer through combination with functional groups and protein domains as well as their defined position and orientation to eachother (determined by the S-layer geometry) it is possible to realize various practical applications ([http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00573.x/full Sleytr et al., 2007]).

Usage and Biology

S-layer proteins can be used as scaffold for nanobiotechnological applications and devices by e.g. fusing the S-layer's self-assembly domain to other functional protein domains. It is possible to coat surfaces and liposomes with S-layers. A big advantage of S-layers: after expressing in E. coli and purification, the nanobiotechnological system is cell-free. This enhances the biological security of a device.

Important parameters

| Experiment | Characteristic | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Expression (E. coli) | Localisation | Cell membrane |

| Compatibility | E. coli KRX | |

| Induction of expression | L-rhamnose for induction of T7 polymerase | |

| Specific growth rate (un-/induced) | 0.248 h-1 / 0.098 h-1 | |

| Doubling time (un-/induced) | 2.79 h / 7.07 h |

Sequence and Features

- 10COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[10]

- 12COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[12]

- 21INCOMPATIBLE WITH RFC[21]Illegal BglII site found at 1102

Illegal XhoI site found at 558 - 23COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[23]

- 25INCOMPATIBLE WITH RFC[25]Illegal NgoMIV site found at 225

Illegal NgoMIV site found at 1314

Illegal NgoMIV site found at 1425

Illegal AgeI site found at 216

Illegal AgeI site found at 457

Illegal AgeI site found at 504 - 1000INCOMPATIBLE WITH RFC[1000]Illegal BsaI site found at 906

Illegal BsaI.rc site found at 213

Illegal BsaI.rc site found at 591

Illegal BsaI.rc site found at 993

Expression in E. coli

The CspB gen was fused with a monomeric RFP (BBa_E1010) using [http://2011.igem.org/Team:Bielefeld-Germany/Protocols#Gibson_assembly Gibson assembly] for characterization.

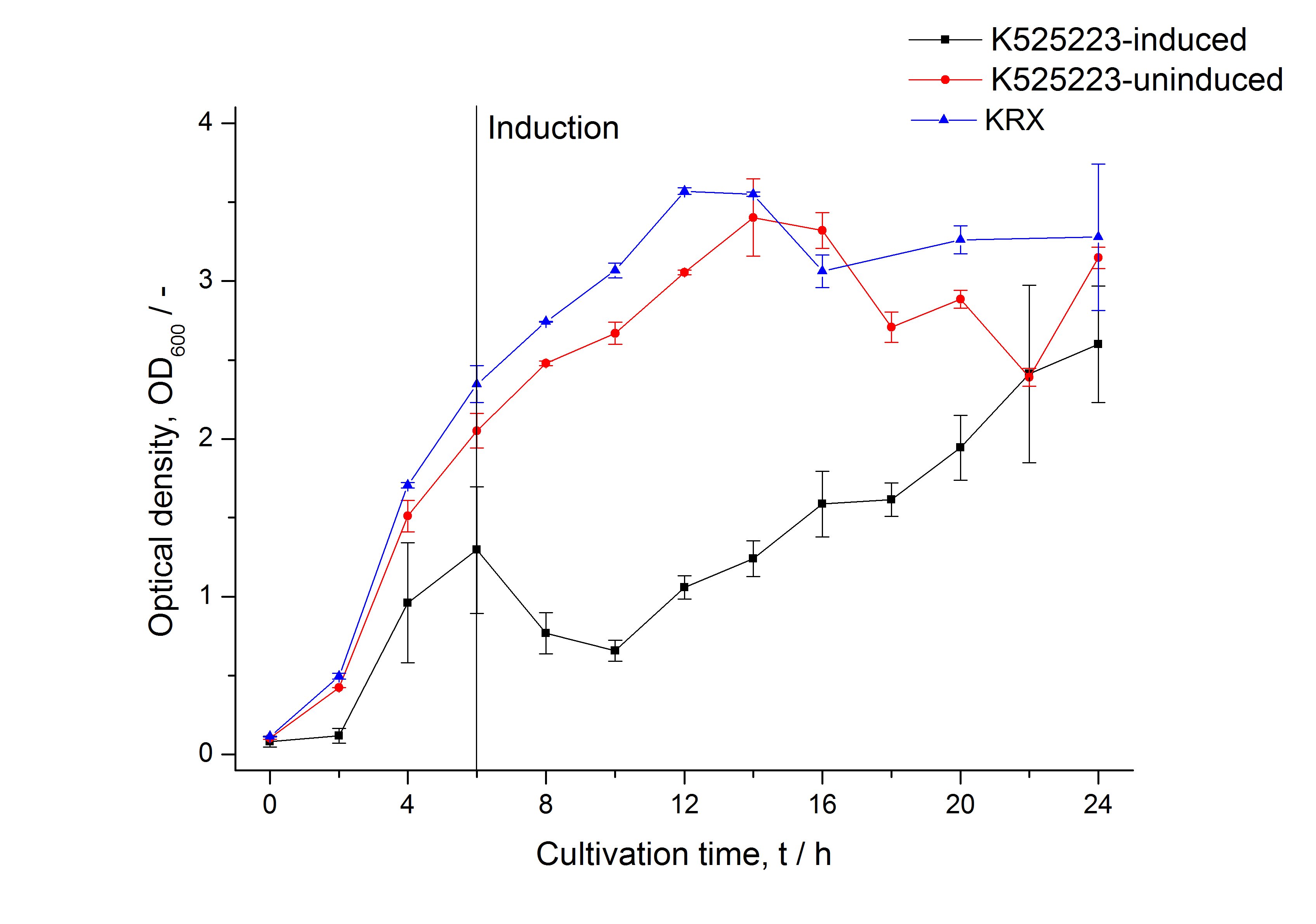

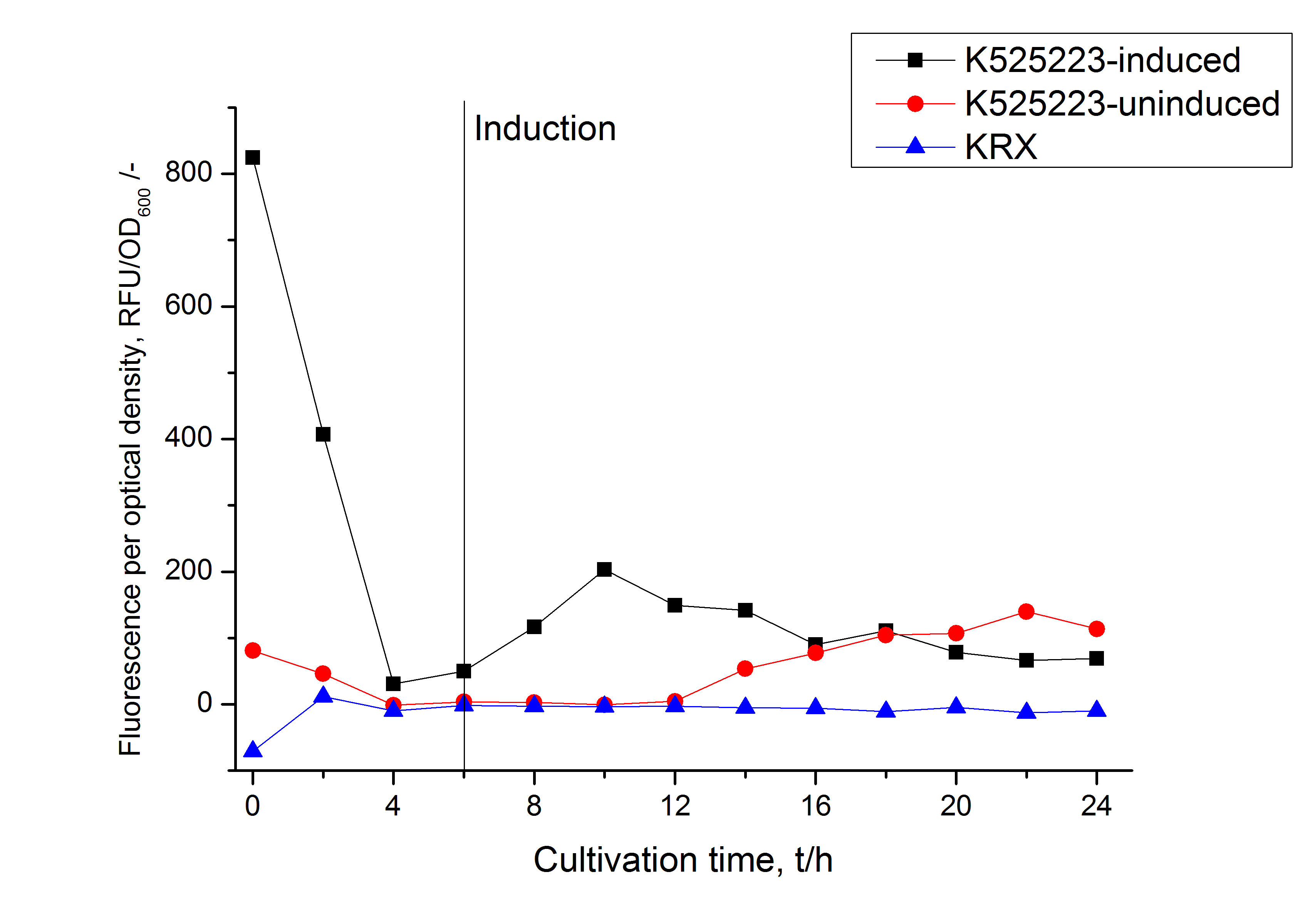

The mRFP|CspB fusion protein was overexpressed in E. coli KRX after induction of T7 polymerase by supplementation of 0,1 % L-rhamnose using the [http://2011.igem.org/Team:Bielefeld-Germany/Protocols/Downstream-processing#Expression_of_S-layer_genes_in_E._coli autinduction protocol] from promega.

Identification and localisation

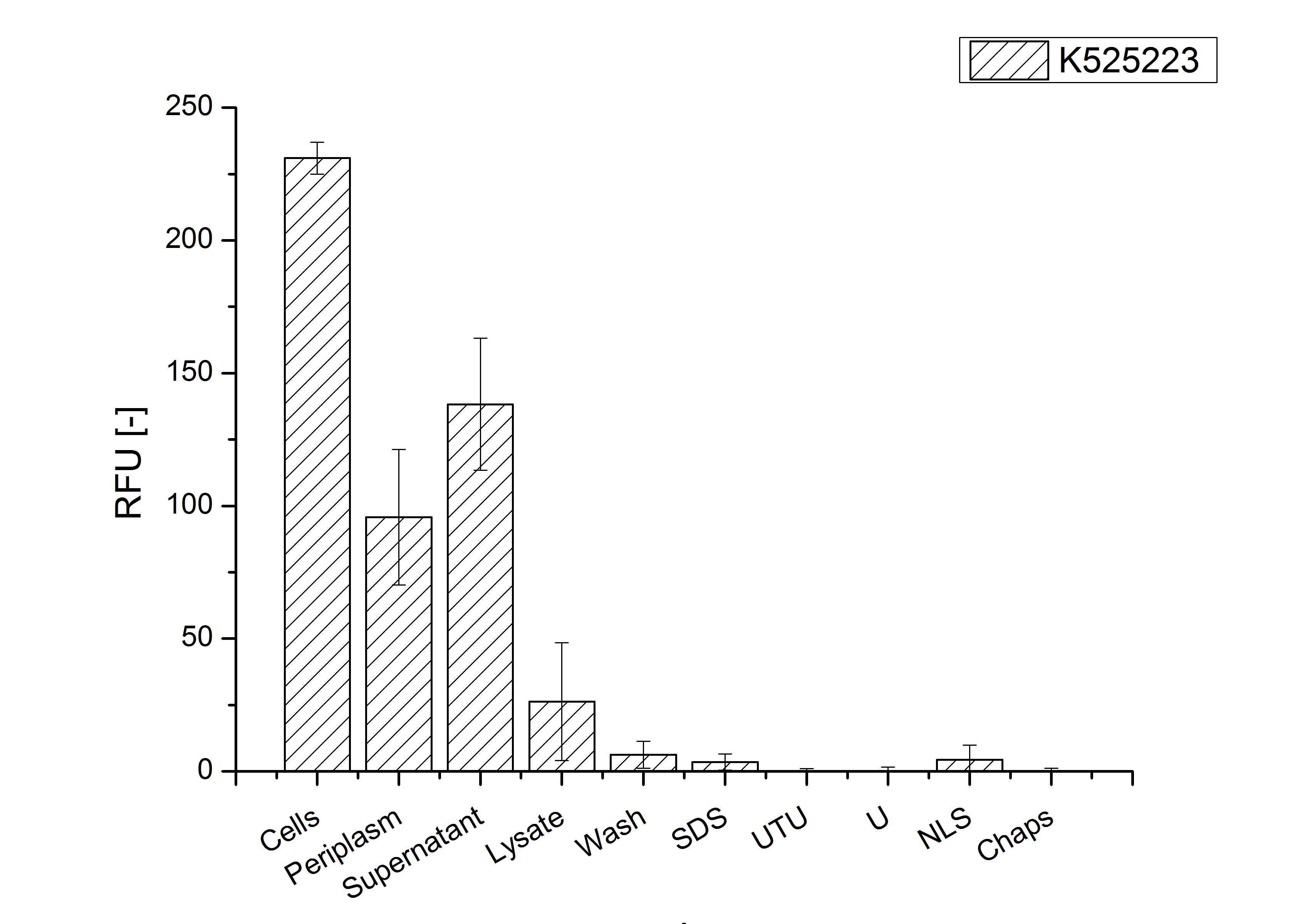

After a cultivation time of 18 h the mRFP|CspB fusion protein has to be localized in E. coli KRX. Therefor a part of the produced biomass was mechanically disrupted and the resulting lysate was wahed with ddH2O. From the other part the periplasm was detached by using a osmotic shock. The high of fluorescene in the periplasma fraction, showed in fig. 3, indicates that Corynebacterium halotolerans TAT-signal sequence is at least in part functional in E. coli KRX.

The S-layer fusion protein could not be found in the polyacrylamide gel after a SDS-PAGE of the lysate. This indicated that the fusion protein intigrates into the cell membrane with its lipid anchor. For testing this assumption the washed lysate was treted with ionic, nonionic and zwitterionic detergents to release the mRFP|CspB out of the membranes.

The existance of flourescence in some detergent fractions and the low fluorescence in the wash fraction confirm the hypothesis of an insertion into the cell membrane (fig. 3). An insertion of these S-layer proteins might stabilize the membrane structure and increase the stability of cells against mechanical and chemical treatment. A stabilization of E. coli expressing S-lyer proteins was discribed by Lederer et al., (2010).

An other important fact is, that there is actually mRFP fluorescence measurable in such high concentrated detergent solutions. The S-layer seems to stabilize the biologically active conformation of mRFP.

In comparison with the mRFP fusion protein of ???, wich has a TAT-sequence, a minor relative fluorescence per OD600 in all cultivation and detergent fractions was detected (fig. 3). Together with the decreasing RFU/OD600 after 9 h of cultivation (fig. 2) indicates this rusult a postive effect of the TAT-sequence on the protein stability.