Difference between revisions of "Part:BBa K2924020"

(→Usage and Biology) |

(→Characterization) |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

===Characterization=== | ===Characterization=== | ||

| − | + | ||

<html> <p align="justify"> | <html> <p align="justify"> | ||

Chromoproteins are a good alternative to fluorescent proteins like red fluorescent protein (RFP). The amilCP protein has an absorption maximum at 588 nm and the blue color can be seen with naked eye. Chromoproteins have the benefit that they can measured by absorption and thus can be used in every laboratory. | Chromoproteins are a good alternative to fluorescent proteins like red fluorescent protein (RFP). The amilCP protein has an absorption maximum at 588 nm and the blue color can be seen with naked eye. Chromoproteins have the benefit that they can measured by absorption and thus can be used in every laboratory. | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

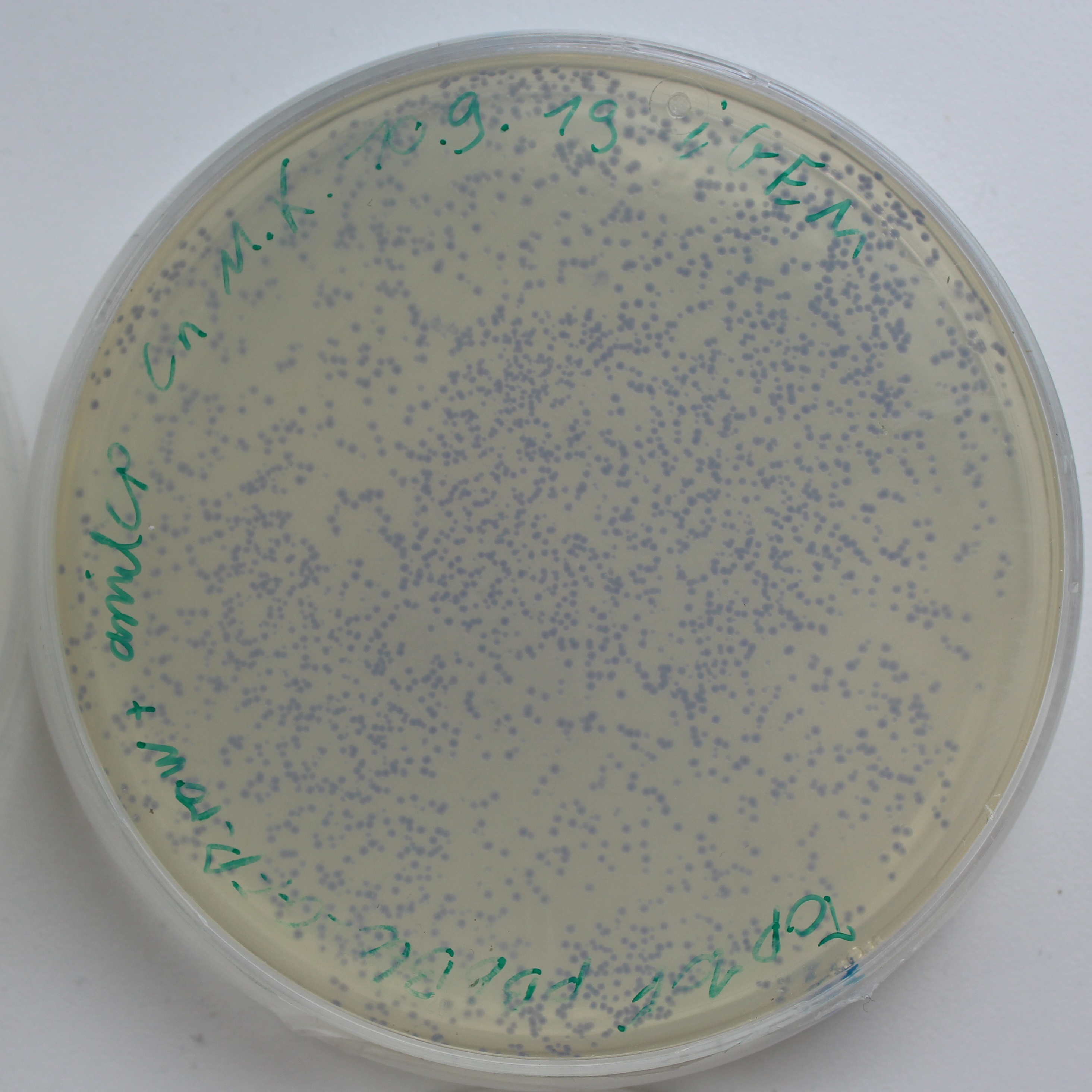

| + | [[File:AmilCP_Colonies.png|thumb|right|300px|<i><b>Fig.1:</b> LB-Agar plate of Escherichia coli Top10F with the pBbB6c + amilCP plasmid. The amilCP makes the colonies blue.</i>]] | ||

| + | <p align="justify"> | ||

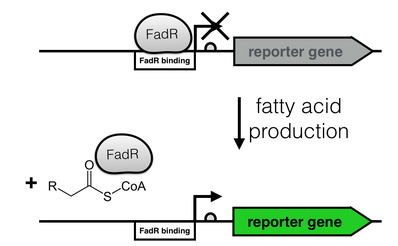

| + | The production of long-chain fatty acids (LCFA) is regulated by the transcription factor FadR. This transcription factor can bind to Acyl-CoA which leads to the release of FadR from its cognate operator sequence, thereby increasing gene expression (as shown in Fig. 2). | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | [[File:FadR_mechanism.png|thumb|left|300px|<i><b>Fig. 2:</b> Regulation of fatty acid metabolism by the transcriptional factor FadR. FadR recognizes its cognate binding site (white), thereby repressing transcription. Upon binding of an Acyl-CoA to FadR, the promoter region is freed, enabling gene expression.</i>]] | ||

| + | <html><p align="justify"> | ||

| + | The constructs were cloned into a variant of the pBbB6c <sup>2</sup> medium copy number backbone which lacked the lac-promoter, with the restriction sites <i>EcoRI</i> and <i>XhoI</i>. This backbone has the antibiotic resistance chloramphenicol and the origin of replication (ori) pBBR1. The <i>Escherichia coli</i> strain Top10F was transformed with this biosensor plasmid, as seen in Figure 3. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:AmilCP_Biosensor_scheme.png|500px|thumb|right|<i><b>Fig.3:</b> Promoter AR with reporter gene amilCP in a pBb backbone. The backbone has a chloramphenicol resistance and a medium copy ori p15A. EcoRI and XbaI were used as restriction enzymes.</i>]] | ||

| + | |||

[[File:PAR_AmilCP_ABCD.png|500px|thumb|right|<i><b>Fig.2:</b> Response of P<sub>AR</sub>+amilCP (blue) to different chain lengths of fatty acids compared to an empty vector control (gray). Plot A presents the response for lauric acid, plot B for myristic acid, plot C for palmitic acid and plot D for stearic acid.</i>]] | [[File:PAR_AmilCP_ABCD.png|500px|thumb|right|<i><b>Fig.2:</b> Response of P<sub>AR</sub>+amilCP (blue) to different chain lengths of fatty acids compared to an empty vector control (gray). Plot A presents the response for lauric acid, plot B for myristic acid, plot C for palmitic acid and plot D for stearic acid.</i>]] | ||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <p align="justify"> | ||

| + | The <a href="https://www.protocols.io/view/transformation-hcnb2ve">transformation</a> of the organism was validated by <a href="https://www.protocols.io/view/e-coli-and-b-subtilis-colony-pcr-8fhhtj6">colony PCR</a>. In some cases, successful transformation could quickly be detected by the different colors of the colonies on the plate and as a cell pellet. | ||

| + | <p align="justify"> | ||

| + | The positive clones were used for experiments and were grown in LB-medium over night. The fatty acid stocks for the experiments were prepared. All of the fatty acids were dissolved in ethanol with the exception of butyric acid, which was dissolved in water. The stock solutions of the fatty acids are shown in Tab.1. | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <style> | ||

| + | th { | ||

| + | text-align: left; | ||

| + | } | ||

| + | table, th, td { | ||

| + | border: 1px solid black; | ||

| + | } | ||

| + | </style> | ||

| + | <table style="width:50%"> | ||

| + | <tr> | ||

| + | <th>Fatty acid</th> | ||

| + | <th>Chain length</th> | ||

| + | <th>MW [g/mol]</th> | ||

| + | <th>Solvent</th> | ||

| + | <th>Solubility</th> | ||

| + | <th>Stock concentration</th> | ||

| + | </tr> | ||

| + | <tr> | ||

| + | <td>Butyric acid</td> | ||

| + | <td|C4:0</td> | ||

| + | <td>88.11</td> | ||

| + | <td>Water</td> | ||

| + | <td>60 g/L</td> | ||

| + | <td>200 mM</td> | ||

| + | </tr> | ||

| + | <tr> | ||

| + | <td>Capric acid</td> | ||

| + | <td|C10:0</td> | ||

| + | <td>172.26</td> | ||

| + | <td>Ethanol</td> | ||

| + | <td>30 g/L</td> | ||

| + | <td>100 mM</td> | ||

| + | </tr> | ||

| + | <tr> | ||

| + | <td>Lauric acid</td> | ||

| + | <td|C12:0</td> | ||

| + | <td>200.32</td> | ||

| + | <td>Ethanol</td> | ||

| + | <td>20 g/L</td> | ||

| + | <td>100 mM</td> | ||

| + | </tr> | ||

| + | <tr> | ||

| + | <td>Myristic acid</td> | ||

| + | <td|C14:0</td> | ||

| + | <td>228.37</td> | ||

| + | <td>Ethanol</td> | ||

| + | <td>15 g/L</td> | ||

| + | <td>75 mM</td> | ||

| + | </tr> | ||

| + | <tr> | ||

| + | <td>Palmitic acid</td> | ||

| + | <td|C16:0</td> | ||

| + | <td>256.42</td> | ||

| + | <td>Ethanol</td> | ||

| + | <td>20 g/L</td> | ||

| + | <td>75 mM</td> | ||

| + | </tr> | ||

| + | <tr> | ||

| + | <td>Stearic acid</td> | ||

| + | <td|C18:0</td> | ||

| + | <td>284.48</td> | ||

| + | <td>Ethanol</td> | ||

| + | <td>20 g/L</td> | ||

| + | <td>50 mM</td> | ||

| + | </tr> | ||

| + | <tr> | ||

| + | <td>Oleic acid</td> | ||

| + | <td|C18:1</td> | ||

| + | <td>282.46</td> | ||

| + | <td>Ethanol</td> | ||

| + | <td>100 g/L</td> | ||

| + | <td>200 mM</td> | ||

| + | </tr> | ||

| + | </table> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | |||

<br><br><br><br><br><br> | <br><br><br><br><br><br> | ||

<html> <p align="justify"> | <html> <p align="justify"> | ||

| Line 32: | Line 126: | ||

<br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br> | <br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br> | ||

| + | |||

===References=== | ===References=== | ||

1: Fuzhong Zhang, James M Carothers, Jay D Keasling. “Design of a dynamic sensor-regulator system for production of chemicals and fuels derived from fatty acids” Nature Biotechnology volume 30, pages 354–359 (2012) | 1: Fuzhong Zhang, James M Carothers, Jay D Keasling. “Design of a dynamic sensor-regulator system for production of chemicals and fuels derived from fatty acids” Nature Biotechnology volume 30, pages 354–359 (2012) | ||

Revision as of 14:42, 21 October 2019

Promoter AR with the chromoprotein amilCP

Long-chain fatty acid sensitive promoter PAR expressing amilCP. This part was used to characterize amilCP.

Usage and Biology

This year the iGEM team from Düsseldorf 2019 was working on the characterization of amilCP, a blue chromoprotein from the Acropora millepora (BBa_K592009) for the use as a reporter gene for a biosensor. For the characterization the synthetic PAR from a previous publication 1 was used and so the biosensor is sensitive for long chain fatty acids (LCFA). The plan was to implement a chromoprotein as a reporter gene, thus enabling to every laboratory to measure a biosensor without fluorescence applications - in contrast, most laboratories have access to a photometer. The chromoprotein amilCP can be observed with the naked eye, in addition to the measurement method by absorption at the wavelength 588 nm for example with a plate reader. Therefore, this option is available for everyone. Sequence and Features

- 10COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[10]

- 12COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[12]

- 21COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[21]

- 23COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[23]

- 25COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[25]

- 1000COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[1000]

Characterization

Chromoproteins are a good alternative to fluorescent proteins like red fluorescent protein (RFP). The amilCP protein has an absorption maximum at 588 nm and the blue color can be seen with naked eye. Chromoproteins have the benefit that they can measured by absorption and thus can be used in every laboratory.

The production of long-chain fatty acids (LCFA) is regulated by the transcription factor FadR. This transcription factor can bind to Acyl-CoA which leads to the release of FadR from its cognate operator sequence, thereby increasing gene expression (as shown in Fig. 2). </html>

The constructs were cloned into a variant of the pBbB6c 2 medium copy number backbone which lacked the lac-promoter, with the restriction sites EcoRI and XhoI. This backbone has the antibiotic resistance chloramphenicol and the origin of replication (ori) pBBR1. The Escherichia coli strain Top10F was transformed with this biosensor plasmid, as seen in Figure 3. [[File:AmilCP_Biosensor_scheme.png|500px|thumb|right|Fig.3: Promoter AR with reporter gene amilCP in a pBb backbone. The backbone has a chloramphenicol resistance and a medium copy ori p15A. EcoRI and XbaI were used as restriction enzymes.]] [[File:PAR_AmilCP_ABCD.png|500px|thumb|right|Fig.2: Response of PAR+amilCP (blue) to different chain lengths of fatty acids compared to an empty vector control (gray). Plot A presents the response for lauric acid, plot B for myristic acid, plot C for palmitic acid and plot D for stearic acid.]]

The transformation of the organism was validated by colony PCR. In some cases, successful transformation could quickly be detected by the different colors of the colonies on the plate and as a cell pellet.

The positive clones were used for experiments and were grown in LB-medium over night. The fatty acid stocks for the experiments were prepared. All of the fatty acids were dissolved in ethanol with the exception of butyric acid, which was dissolved in water. The stock solutions of the fatty acids are shown in Tab.1.

| Fatty acid | Chain length | MW [g/mol] | Solvent | Solubility | Stock concentration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Butyric acid | 88.11 | Water | 60 g/L | 200 mM | |

| Capric acid | 172.26 | Ethanol | 30 g/L | 100 mM | |

| Lauric acid | 200.32 | Ethanol | 20 g/L | 100 mM | |

| Myristic acid | 228.37 | Ethanol | 15 g/L | 75 mM | |

| Palmitic acid | 256.42 | Ethanol | 20 g/L | 75 mM | |

| Stearic acid | 284.48 | Ethanol | 20 g/L | 50 mM | |

| Oleic acid | 282.46 | Ethanol | 100 g/L | 200 mM |

The experiments with the blue chromoprotein amilCP showed that the production of the chromoprotein is increased by a higher concentration of fatty acids in the medium. The best result was achieved with the fatty acid stearic acid. The biosensor also worked for the chain lengths from C14:0 and C16:0. The EVC is in thus experiments lower than the samples with amilCP. By adding lauric acid (C12:0) to the culture medium the production of amilCP increased, but the EVC also increased a lot and is close to amilCP, so it is not certain if this result can be used for an nearly distinct conclusion.