Difference between revisions of "Part:BBa K3202068"

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

However, during the experiment we tested that the RBS1 (Fig. 2) sequence provided by the original article fails to function in our circuit, we found RBS2 (Fig. 3) with a different working mechanism. The structure of AUGA in RBS2 acts as both the stop codon (AUG) of the former gene sequence, releasing the former peptide chain; takes a step (gene code) backward, pinpointing a new ribosome binding site, and initiated the translation of next gene sequence with the start codon (UGA). However, finally we still used RBS1 since the crux actually lied in another place. | However, during the experiment we tested that the RBS1 (Fig. 2) sequence provided by the original article fails to function in our circuit, we found RBS2 (Fig. 3) with a different working mechanism. The structure of AUGA in RBS2 acts as both the stop codon (AUG) of the former gene sequence, releasing the former peptide chain; takes a step (gene code) backward, pinpointing a new ribosome binding site, and initiated the translation of next gene sequence with the start codon (UGA). However, finally we still used RBS1 since the crux actually lied in another place. | ||

| − | [[File: T--BHSF ND--Bistable design 2.png | | + | [[File: T--BHSF ND--Bistable design 2.png |432px|thumb|left|alt=RBS1 from the Original Article |Figure 2]] |

| − | [[File: T--BHSF ND--Bistable design 3.png | | + | [[File: T--BHSF ND--Bistable design 3.png |432px|thumb|right|alt=RBS1 with a Different Working Mechanism |Figure 3]] |

===sRNA=== | ===sRNA=== | ||

Revision as of 14:20, 20 October 2019

AraC-Pc-pBAD-RBS1-Colicin E2-T500-T1/TE-MicCsRNA-PA1/O4

This composite part is designed to insert the toxin Colicin E2 into the bistable system.

Presenting with BBa_K3202066-BBa_K3202067, this part is to test the function of the toxin within our bistable system.

Background

We are inspired by a lately published article written by Belén Calles, Angel Goñi-Moreno, and Víctor de Lorenzo to design a double-bistable system which achieves zero basal expression of gene of interest in the absence of any inducer while ensuring constant transcriptional capacities and induction rates among promoters.

“The mechanism of a bistable system is elaborated below: a repressor transcriptionally inhibits the promoter which is responsible for the transcription of sRNA, while the sRNA translationally inhibits the repressor. The gene of interest is translationally coupled to the repressor gene. That is to say, the repressor protein R targets the strong promoter which the inhibitory sRNA is produced, so that R and sRNA are mutually inhibitory. Such arrangement helps to minimize the basal activity of the inducible module and thus suppress leaky gene expression levels.”

Design

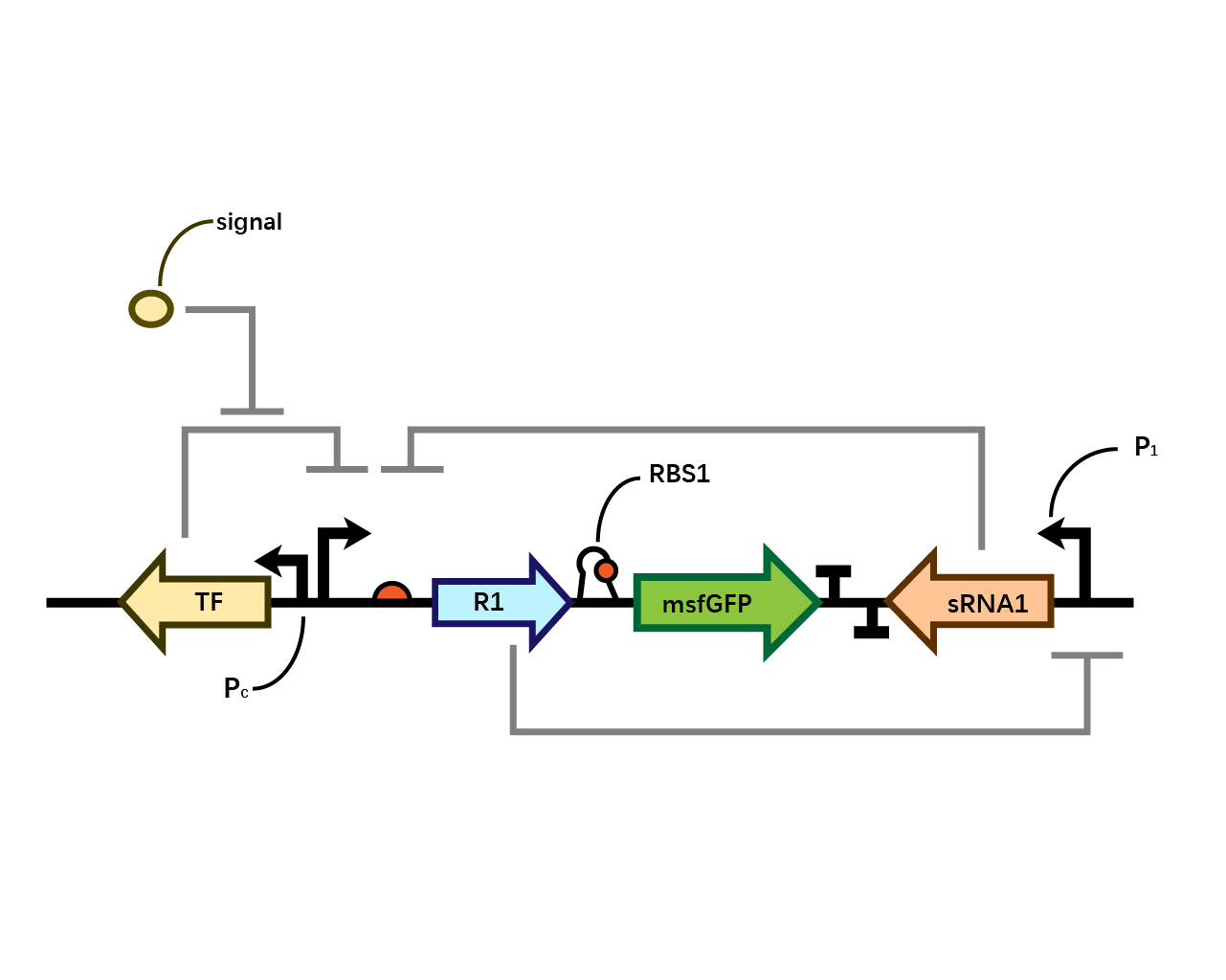

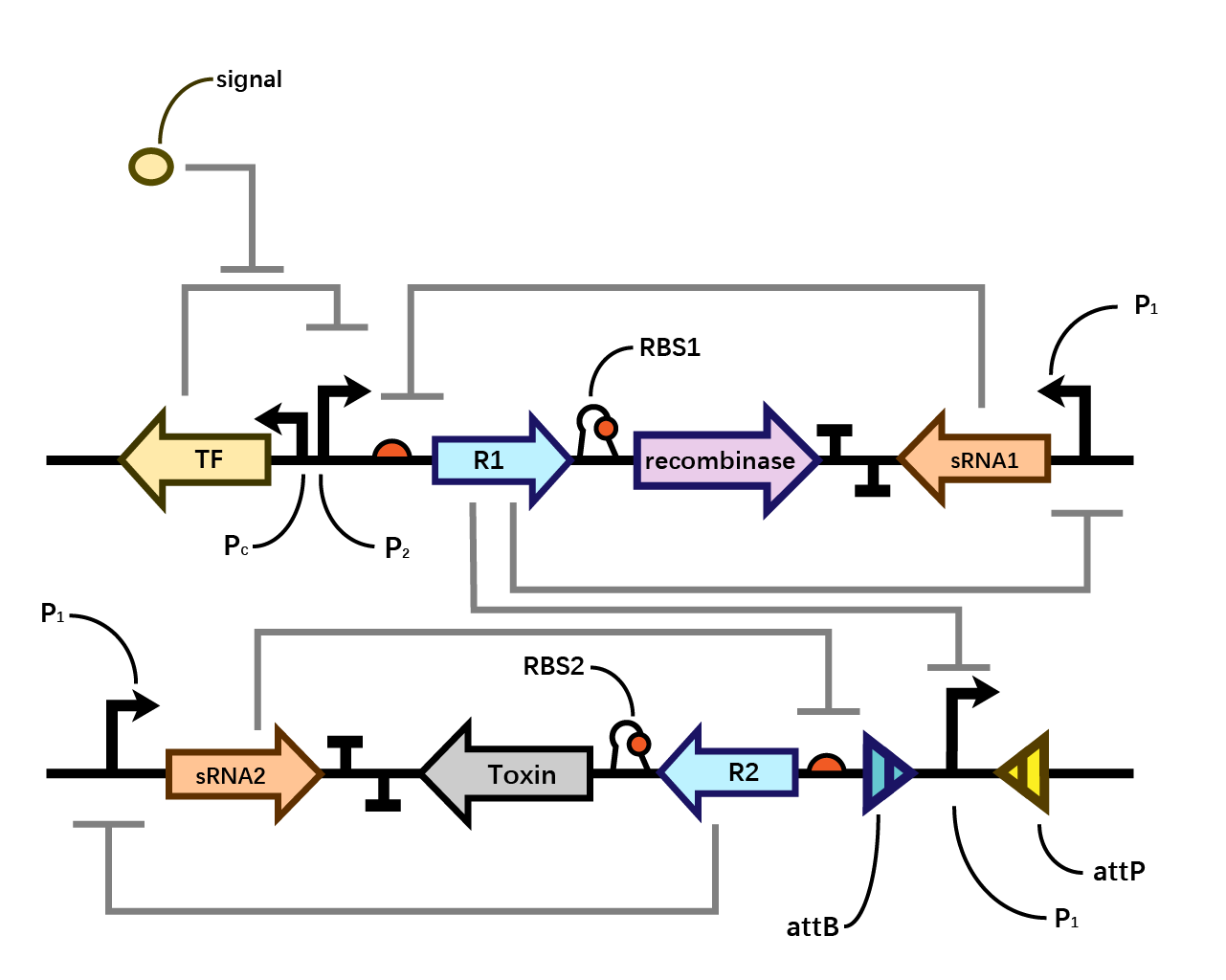

In our system(Fig. 1), we have transcriptional repressors R1 and R2 expressed through the inducible promoter but translationally inhibited by the MicC sRNA1 and sRNA2 respectively, since RBS2 and RBS3 is directly inhibited by sRNA while they initiates the transcription of the two repressors; the gene of interest is translationally coupled to the repressor gene while three promoters which produces the inhibitory sRNA are targeted by their corresponding repressors. Therefore, repressors and sRNAs are mutually inhibitory.

RBS1

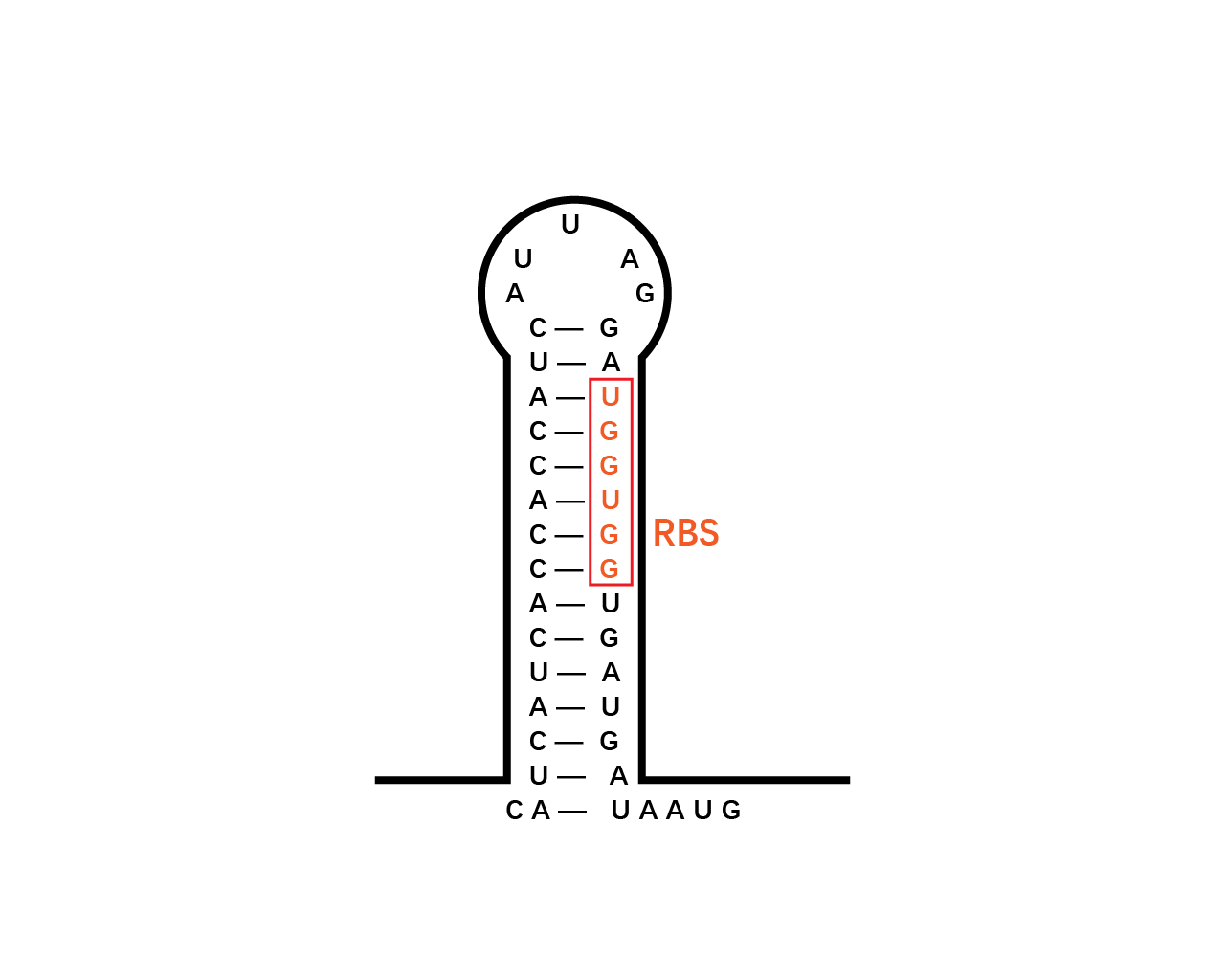

The control of the recombinase in coordination with the upstream repressor gene, which is the target of the sRNA, requires a translational coupler cassette. “An efficient mechanism to reach this goal is based on the ability of translating ribosomes to unfold mRNA secondary structures. In our design, translational coupling is achieved by occluding the RBS of gene of interest by formation of a secondary mRNA structure, containing a His-tag sequence added to the 3 ́end of the repressor gene. The hairpin structure prevents the ribosomal recruitment to the recombinase and therefore its translation. In contrast, when the upstream repressor mRNA is actively translated, the 70s ribosome disrupts inhibitory mRNA secondary structure in the downstream gene translation initiation region thus allowing its expression.”

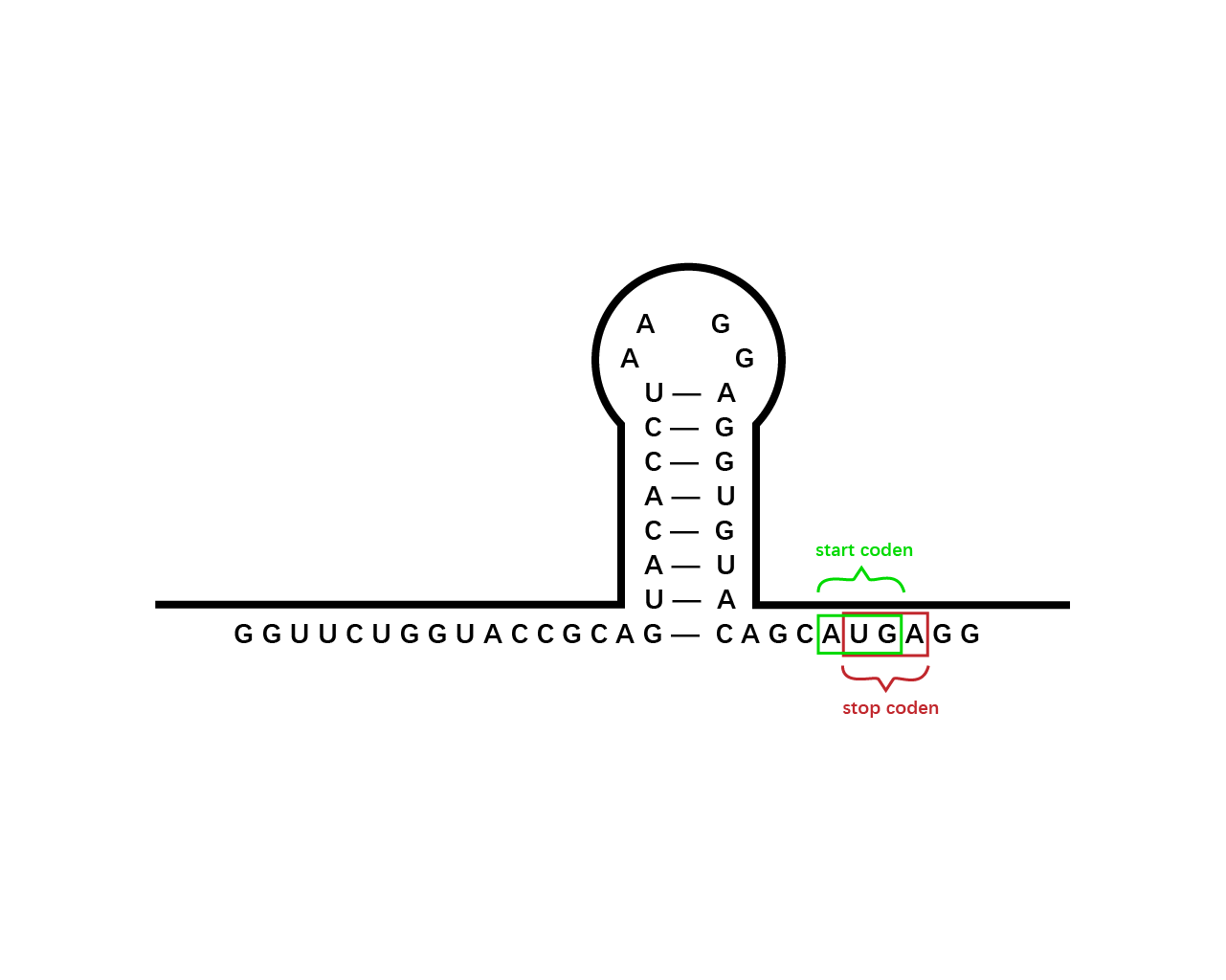

However, during the experiment we tested that the RBS1 (Fig. 2) sequence provided by the original article fails to function in our circuit, we found RBS2 (Fig. 3) with a different working mechanism. The structure of AUGA in RBS2 acts as both the stop codon (AUG) of the former gene sequence, releasing the former peptide chain; takes a step (gene code) backward, pinpointing a new ribosome binding site, and initiated the translation of next gene sequence with the start codon (UGA). However, finally we still used RBS1 since the crux actually lied in another place.

sRNA

Small non‐coding RNAs (sRNAs) have important functions as genetic regulators in prokaryotes. “sRNAs act post‐transcriptionally through complementary pairing with target mRNAs to regulate protein expression. Antisense sRNAs negatively regulates proteins by destabilizing the target protein's mRNA. Antisense sRNAs prevent translation by binding to the target mRNAs in a process mediated by the RNA chaperone Hfq.” On binding, both the mRNAs and sRNAs are degraded, suggesting that prokaryotic sRNAs—unlike their eukaryotic counterparts—act stoichiometrically on their targets.

Repressor

“A DNA-binding repressor blocks the attachment of RNA polymerase to the promoter, thus preventing transcription of the genes into messenger RNA.”

We assume that when the whole system is applied to a factory, the situation where inducer is present is in the working condition of the bacterium. Within one single layer of the bistable system, the transcriptional factor is turned on, Pm initiates the expression of R1, which raises the concentration of R1 and thereby exerts greater inhibition on PR1 and therefore decreases the concentration of sRNA1. As sRNA1 is inhibited the inhibitory effect it exerts on R1 accordingly decreases, therefore the recombinase is expressed through the first layer, and vice versa. Nevertheless, given that the expression of R1 inhibits PR1, even if the recombinase is expressed PR1 can be flipped over but cannot express the second layer. Since there is no further input signal to the second layer of the bistable system, the inhibitory effect of sRNA2 dominates over R2, therefore, both R2 and the toxin cannot be expressed. That is to say, the additional second layer ensures that there is no leakage of toxin when inducer is present.

However, when the bacterium is stolen and thereby inducer isn’t present, the transcriptional factor is turned off, promoter Pm doesn’t work. Therefore, sRNA1 dominates over R1 and then the recombinase is not expressed in the first layer. Since there is a decrease in the expression of R1, the inhibitory effect it exerts on PR1 decreases, therefore PR1 which has already been flipped over when inducer is present (working condition) initiates the expression of R2. Applying the same logic, finally R2 dominates over sRNA2 and expresses the toxin to kill the cell. (Fig. 4)

Why double layer?

The reason why we designed such double-bistable system can be attributed to the consideration that the double-decked bistable systems of both recombinase and toxin could further reinforce the insurance of zero expression of toxin.

When the second bistable system coupling the toxin with the first layer of recombinase, double insurance of zero expression of recombinase and toxin is achieved. However, as the diagram shown below, a single bistable system where toxin is coupled without the second layer of insurance could collapse if the mutual inhibitory effect of repressor and sRNA within the first layer malfunctions. Whereas such concern could be eliminated by the second layer of toxin with a bistable system around.

Sequence and Features

- 10COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[10]

- 12COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[12]

- 21INCOMPATIBLE WITH RFC[21]Illegal BamHI site found at 1144

- 23COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[23]

- 25INCOMPATIBLE WITH RFC[25]Illegal AgeI site found at 979

- 1000INCOMPATIBLE WITH RFC[1000]Illegal SapI site found at 961