Difference between revisions of "Part:BBa K525121"

| Line 205: | Line 205: | ||

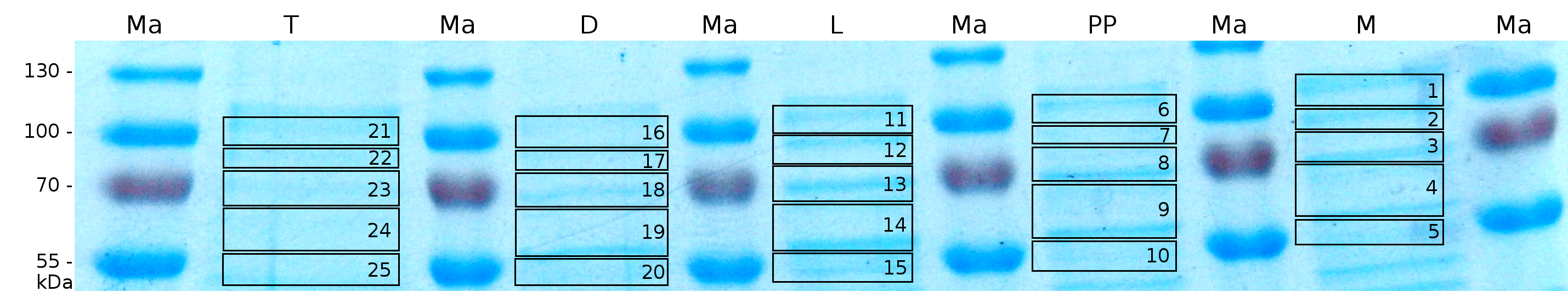

[[Image:Bielefeld2011_K525131_BF1_maldi_graph.png|700px|thumb|center| '''Figure 5: MALDI TOF measurement of CspB/mRFP [https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_E1010 (BBa_E1010)] fusion protein. Samples are arranged after estimated molecular mass of the gel slice. Measurement was performed with a ultrafleXtreme<sup>TM</sup> by Bruker Daltonics using the software FlexAnalysis, Biotools and SequenceEditor.''']] | [[Image:Bielefeld2011_K525131_BF1_maldi_graph.png|700px|thumb|center| '''Figure 5: MALDI TOF measurement of CspB/mRFP [https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_E1010 (BBa_E1010)] fusion protein. Samples are arranged after estimated molecular mass of the gel slice. Measurement was performed with a ultrafleXtreme<sup>TM</sup> by Bruker Daltonics using the software FlexAnalysis, Biotools and SequenceEditor.''']] | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br style="clear: both" /> | ||

As expected, only minor sequence coverage was found in the periplasmatic fraction, due to the lipid anchor located at the carboxy-terminus. This hydrophobic region inhibits the transport of the protein to the periplasm, mediated by the amino-terminal TAT-sequence. Little fluorescence was also found in the lysis fraction, verifying our assumtion, that the protein integrates or strongly binds to the cell membrane. Using urea to disintegrate the S-layer fusion protein from the cell membrane resulted only in a slightly higher sequence coverage. However, washing the pellet with 2 % Triton X-100 (v/v), 2 % SDS (w/v), previously treated with urea, resulted in a higher sequence coverage and can therefore be expected as more applicable to desintegrate the S-layer fusion protein. Sequence coverage in the supernatant of the cultivation medium can be explained with the late phase of cultivation where some cells are lysed. | As expected, only minor sequence coverage was found in the periplasmatic fraction, due to the lipid anchor located at the carboxy-terminus. This hydrophobic region inhibits the transport of the protein to the periplasm, mediated by the amino-terminal TAT-sequence. Little fluorescence was also found in the lysis fraction, verifying our assumtion, that the protein integrates or strongly binds to the cell membrane. Using urea to disintegrate the S-layer fusion protein from the cell membrane resulted only in a slightly higher sequence coverage. However, washing the pellet with 2 % Triton X-100 (v/v), 2 % SDS (w/v), previously treated with urea, resulted in a higher sequence coverage and can therefore be expected as more applicable to desintegrate the S-layer fusion protein. Sequence coverage in the supernatant of the cultivation medium can be explained with the late phase of cultivation where some cells are lysed. | ||

| Line 213: | Line 215: | ||

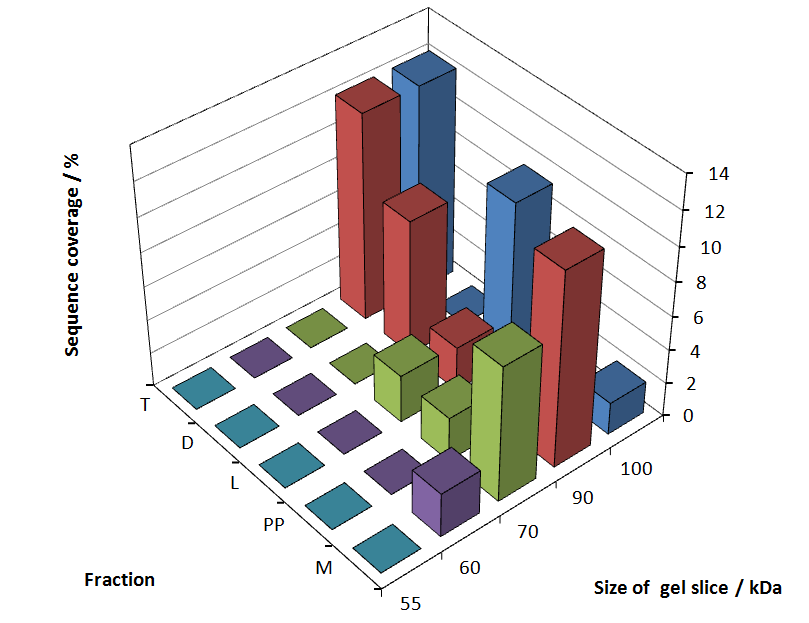

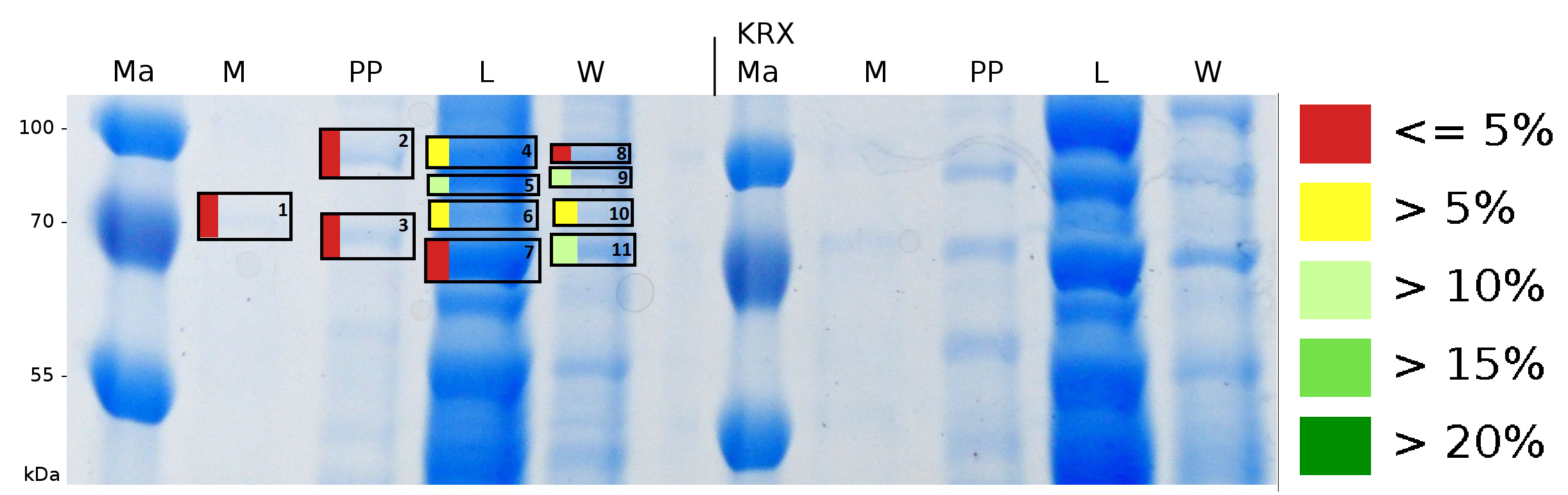

[[Image:Bielefeld2011_Maldi_Legende.png|120px|thumb|left| '''Figure 6: Marker for sequence coverage of gel slices measured with MALDI TOF.''']] | [[Image:Bielefeld2011_Maldi_Legende.png|120px|thumb|left| '''Figure 6: Marker for sequence coverage of gel slices measured with MALDI TOF.''']] | ||

[[Image:Bielefeld2011_K525131_BF1_Gel1.png|750px|thumb|right| '''Figure 7: MALDI-TOF measurement of CspB/mRFP [https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_E1010 (BBa_E1010)] fusion protein in different fractions. Abbreviations are Ma: Marker (PageRuler <sup>TM</sup> Prestained Protein Ladder SM0671), M (medium), PP (periplasm), L (cell lysis with ribolyser), W (wash with ddH<sub>2</sub>O). In the left half of the gel fractions of ''E. coli'' KRX with induced production of fusion protein, the right half shows fractions of ''E. coli'' KRX without carrying the plasmid coding the fusion protein. Colours show the sequence coverage of the gel lane, cutted out of the gel.''']] | [[Image:Bielefeld2011_K525131_BF1_Gel1.png|750px|thumb|right| '''Figure 7: MALDI-TOF measurement of CspB/mRFP [https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_E1010 (BBa_E1010)] fusion protein in different fractions. Abbreviations are Ma: Marker (PageRuler <sup>TM</sup> Prestained Protein Ladder SM0671), M (medium), PP (periplasm), L (cell lysis with ribolyser), W (wash with ddH<sub>2</sub>O). In the left half of the gel fractions of ''E. coli'' KRX with induced production of fusion protein, the right half shows fractions of ''E. coli'' KRX without carrying the plasmid coding the fusion protein. Colours show the sequence coverage of the gel lane, cutted out of the gel.''']] | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br style="clear: both" /> | ||

Sequence coverage was only found in the wash and the lysis fraction, again indicating that the S-layer protein is integrating in the cell membrane. Thus transport to the periplasm mediated through the amino-terminal TAT-sequence cannot take place or after transport to the periplasm binds to the inner cell membrane. | Sequence coverage was only found in the wash and the lysis fraction, again indicating that the S-layer protein is integrating in the cell membrane. Thus transport to the periplasm mediated through the amino-terminal TAT-sequence cannot take place or after transport to the periplasm binds to the inner cell membrane. | ||

Revision as of 00:48, 22 September 2011

S-layer cspB from Corynebacterium glutamicum with TAT-Sequence and lipid anchor, PT7 and RBS

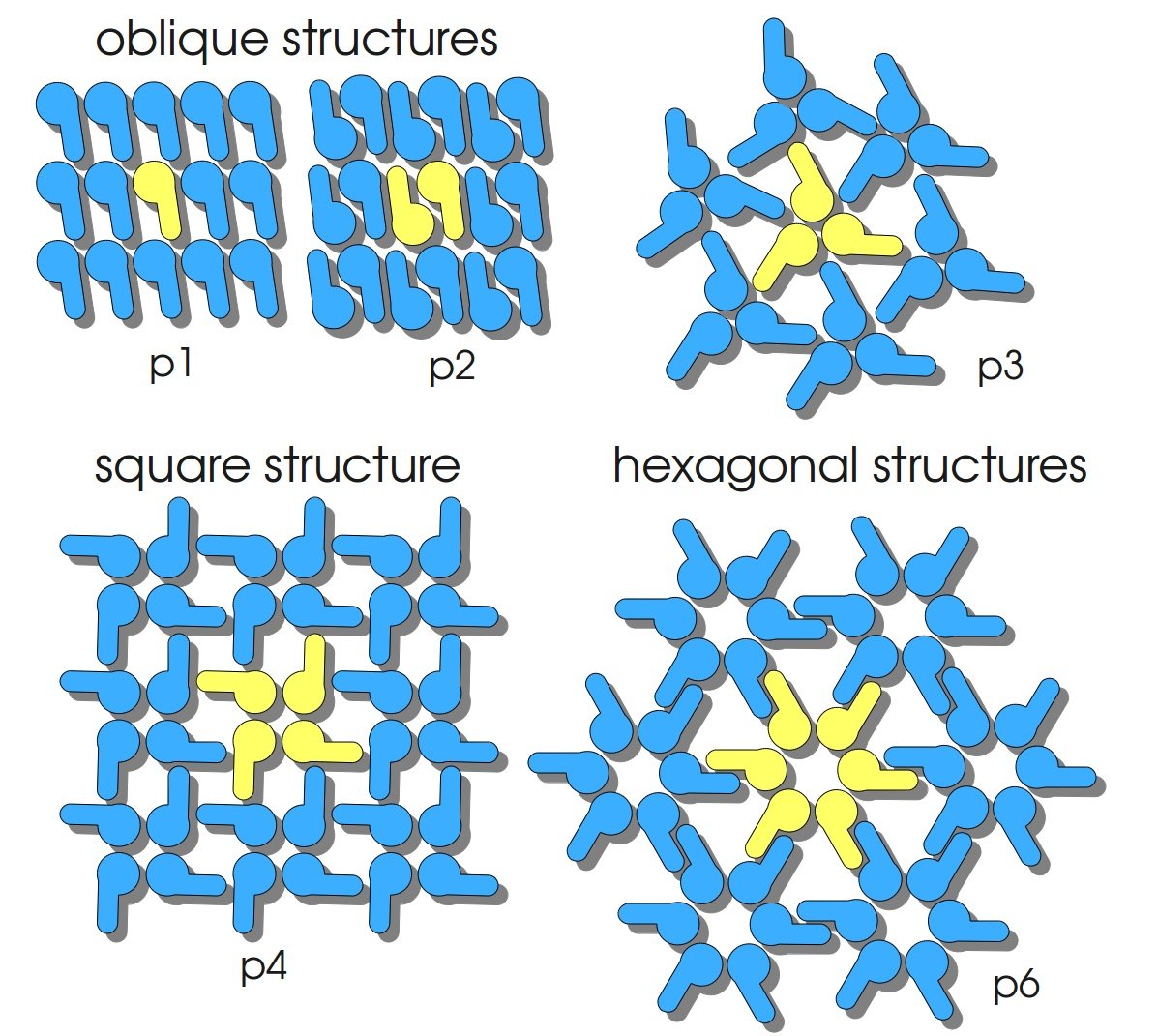

S-layers (crystalline bacterial surface layer) are crystal-like layers consisting of multiple protein monomers and can be found in various (archae-)bacteria. They constitute the outermost part of the cell wall. Especially their ability for self-assembly into distinct geometries is of scientific interest. At phase boundaries, in solutions and on a variety of surfaces they form different lattice structures. The geometry and arrangement is determined by the C-terminal self assembly-domain, which is specific for each S-layer protein. The most common lattice geometries are oblique, square and hexagonal. By modifying the characteristics of the S-layer through combination with functional groups and protein domains as well as their defined position and orientation to eachother (determined by the S-layer geometry) it is possible to realize various practical applications ([http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00573.x/full Sleytr et al., 2007]).

Usage and Biology

S-layer proteins can be used as scaffold for nanobiotechnological applications and devices by e.g. fusing the S-layer's self-assembly domain to other functional protein domains. It is possible to coat surfaces and liposomes with S-layers. A big advantage of S-layers: after expressing in E. coli and purification, the nanobiotechnological system is cell-free. This enhances the biological security of a device.

The S-layer of C. glutamicum is characterized by a hexagonal lattice symmetry. Attachment between S-layer and cell wall was found to be due to the hydrophobic carboxy-terminus of the PS2 protein ([http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S016816560400241X Hansmeier et al., 2004]).

Important parameters

| Experiment | Characteristic | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Expression (E. coli) | ||

| Compatibility | E. coli KRX | |

| Inductor | L-rhamnose | |

| Medium | Autoinduction (LB + L-rhamnose) | |

| Optimal temperature | 37 °C | |

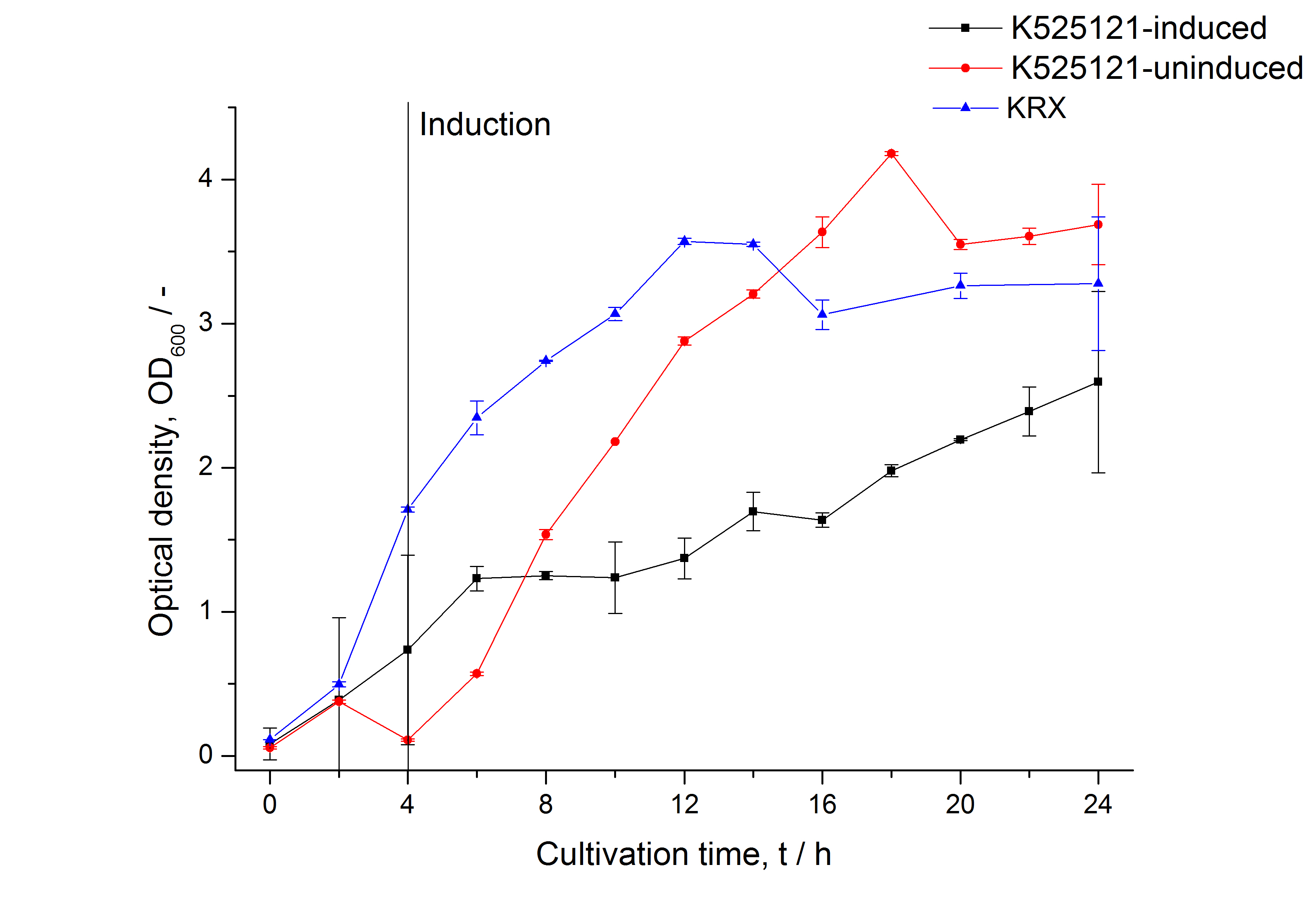

| Specific growth rate (un-/induced) | 0.260 h-1 / 0.106 h-1 | |

| Doubling time (un-/induced) | 2.67 h / 6.52 h | |

| Characterization | ||

| Number of amino acids | 461 | |

| Molecular weight | 50.6 kDa | |

| Theoretical pI | 4.21 | |

| Localization | mainly cell membrane | |

| partially culture supernatant | ||

| partially cytoplasm | ||

| not periplasm |

Sequence and Features

- 10COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[10]

- 12COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[12]

- 21INCOMPATIBLE WITH RFC[21]Illegal BamHI site found at 1421

Illegal XhoI site found at 248

Illegal XhoI site found at 866 - 23COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[23]

- 25COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[25]

- 1000INCOMPATIBLE WITH RFC[1000]Illegal BsaI.rc site found at 1400

Illegal SapI site found at 647

Illegal SapI site found at 859

Illegal SapI site found at 1407

Expression in E. coli

For characterizations, the cspB gene was fused to a monomeric RFP (BBa_E1010) using Gibson assembly.

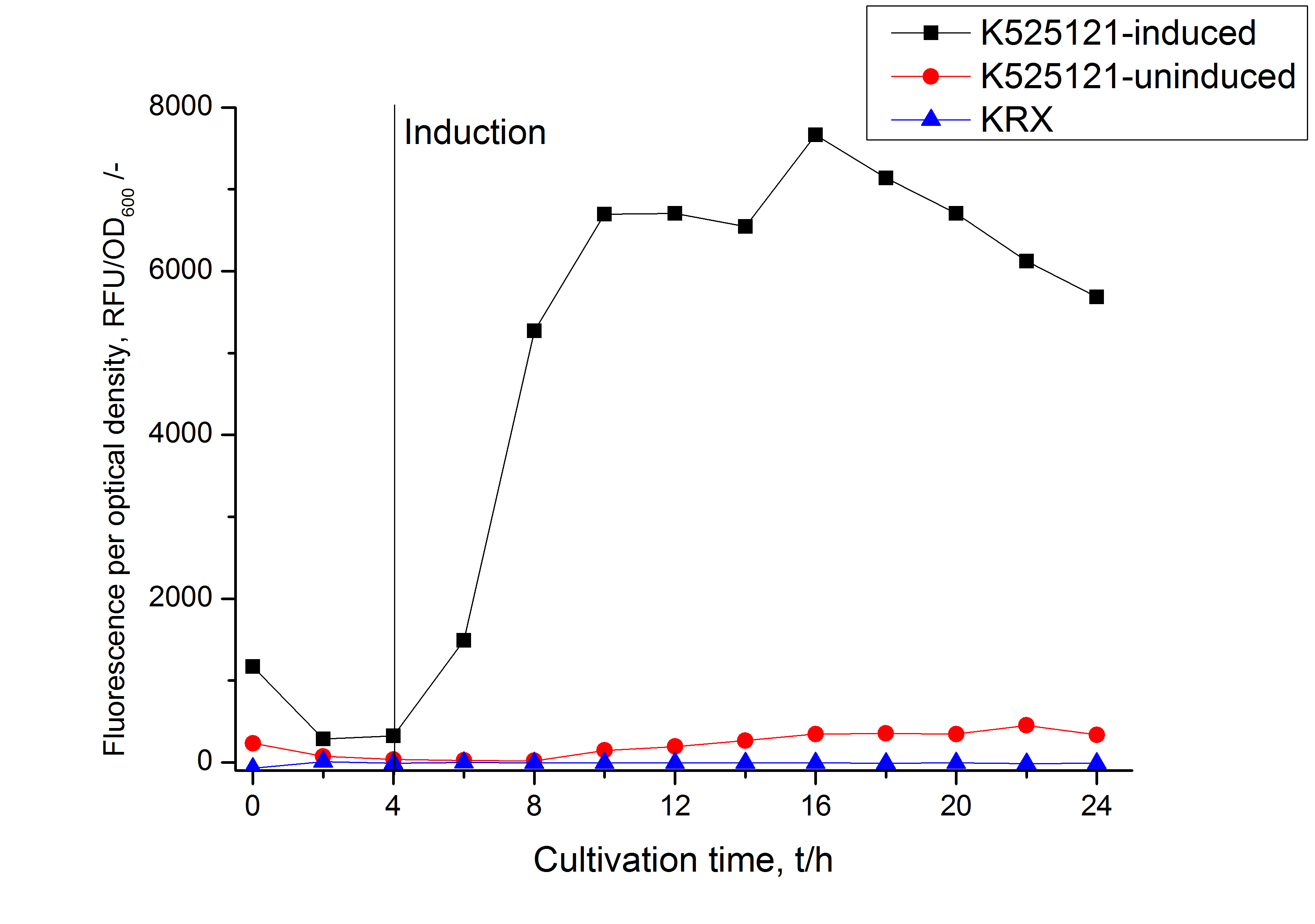

The CspB|mRFP fusion protein was overexpressed in E. coli KRX after induction of a T7 polymerase gene in the KRX's genome by supplementation of 0.1 % L-rhamnose using the autinduction protocol developed by Promega.

Identification and localisation

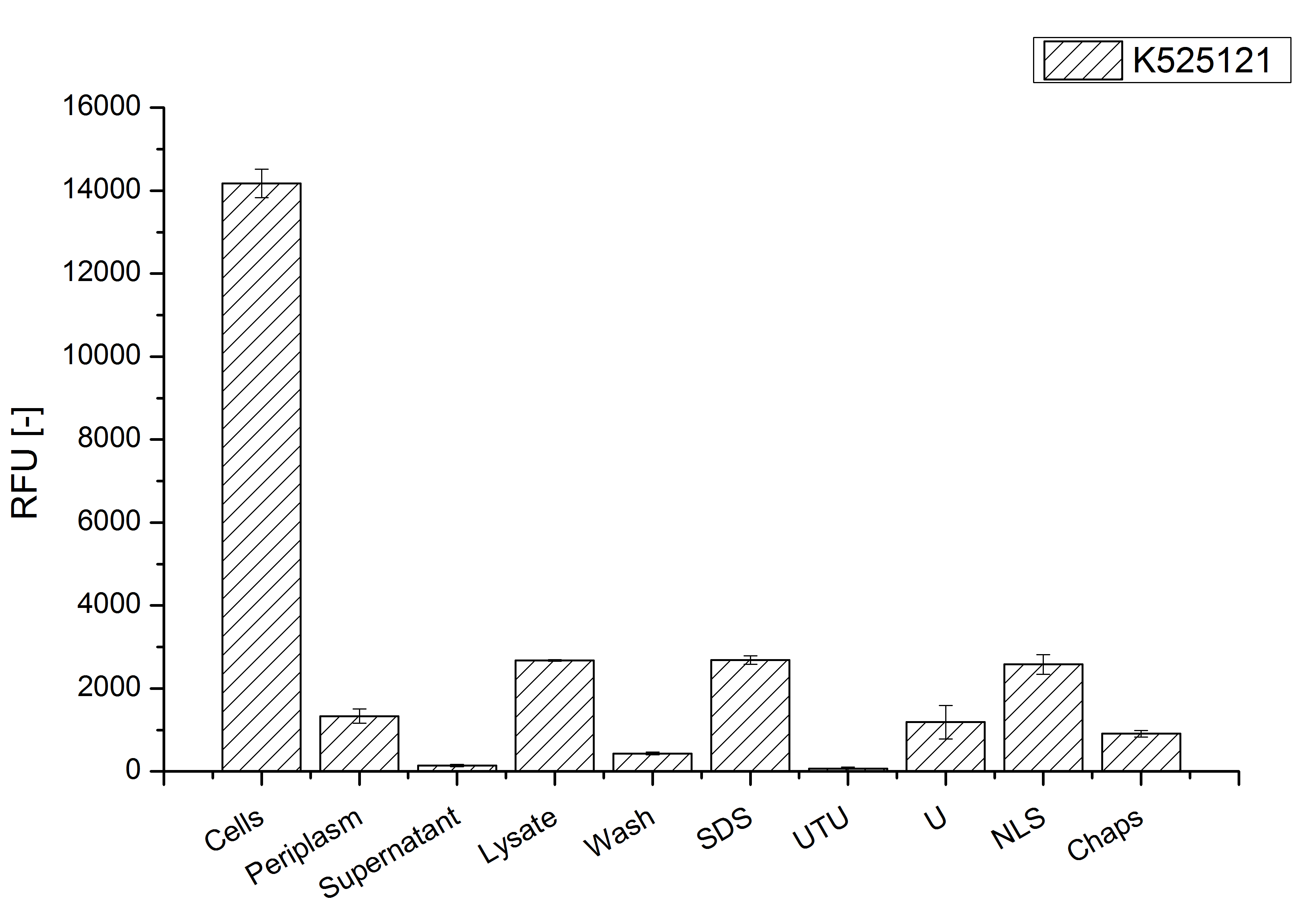

After a cultivation time of 18 h the mRFP|CspB fusion protein has to be localized in E. coli KRX. Therefore a part of the produced biomass was mechanically disrupted and the resulting lysate was washed with ddH2O. The periplasm was detached by using a osmotic shock from other parts of the cells. The existance of fluorescene in the periplasm fraction, showed in fig. 3, indicates that C. glutamicum TAT-signal sequence is at least in part functional in E. coli KRX.

The S-layer fusion protein could not be found in the polyacrylamide gel after a SDS-PAGE of the lysate and the cell debris were still red. This indicates that the fusion protein intigrates with the lipid anchor into the cell membrane. For testing this assumption the washed lysate was treated with ionic, nonionic and zwitterionic detergents to release the mRFP|CspB out of the membranes.

The existance of flourescence in the detergent fractions and the proportionally to the lysis fraction low fluorescence in the wash fraction confirm the hypothesis of an insertion into the cell membrane (fig. 3). An insertion of these S-layer proteins might stabilize the membrane structure and increase the stability of cells against mechanical and chemical treatment. A stabilization of E. coli expressing S-layer proteins was discribed by Lederer et al., (2010).

An other important fact is, that there is actually mRFP fluorescence measurable in such high concentrated detergent solutions. The S-layer seems to stabilize the biologically active conformation of mRFP. The MALDI-TOF analysis of the relevant size range in the polyacrylamid gel approved the existance of the intact fusion protein in all detergent fractions (fig 4).

MALDI-TOF analysis was first used to identify the location of the fusion protein in different fractions. Fractions of medium supernatant after cultivation, periplasmatic isolation, cell lysis, denaturation in 6 M urea and the following wash with 2 % (v/v) Triton X-100, 2 % SDS (w/v) were loaded onto a SDS-PAGE and fragments of the gel were measured with MALDI-TOF.

The following table shows the sequence coverage (in %) of our measurable gel samples with the amino acid sequence of fusion protein CspB/mRFP (BBa_E1010).

| number of gel sample | sequence coverage (%) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1.9 |

| 2 | 11.5 |

| 3 | 8.0 |

| 4 | 2.6 |

| 5 | 0.0 |

| 6 | 0.0 |

| 7 | 2.6 |

| 8 | 0.0 |

| 9 | 0.0 |

| 10 | 0.0 |

| 11 | 9.4 |

| 12 | 2.6 |

| 13 | 2.8 |

| 14 | 0.0 |

| 15 | 0.0 |

| 16 | 0.0 |

| 17 | 8.0 |

| 18 | 0.0 |

| 19 | 0.0 |

| 20 | 0.0 |

| 21 | 12.2 |

| 22 | 12.2 |

| 23 | 0.0 |

| 24 | 0.0 |

| 25 | 0.0 |

Fig. 5 shows these data. The gel samples were arranged after estimated molecular mass cut out from the gel.

As expected, only minor sequence coverage was found in the periplasmatic fraction, due to the lipid anchor located at the carboxy-terminus. This hydrophobic region inhibits the transport of the protein to the periplasm, mediated by the amino-terminal TAT-sequence. Little fluorescence was also found in the lysis fraction, verifying our assumtion, that the protein integrates or strongly binds to the cell membrane. Using urea to disintegrate the S-layer fusion protein from the cell membrane resulted only in a slightly higher sequence coverage. However, washing the pellet with 2 % Triton X-100 (v/v), 2 % SDS (w/v), previously treated with urea, resulted in a higher sequence coverage and can therefore be expected as more applicable to desintegrate the S-layer fusion protein. Sequence coverage in the supernatant of the cultivation medium can be explained with the late phase of cultivation where some cells are lysed.

To obtain more specific informations about the location of the S-layer fusion protein, after comparison with same treated fraction of E. coli KRX all gel bands in a defined size area were cut out of the gel and analysed with MALDI-TOF. Results are shown in fig. 7.

Sequence coverage was only found in the wash and the lysis fraction, again indicating that the S-layer protein is integrating in the cell membrane. Thus transport to the periplasm mediated through the amino-terminal TAT-sequence cannot take place or after transport to the periplasm binds to the inner cell membrane.

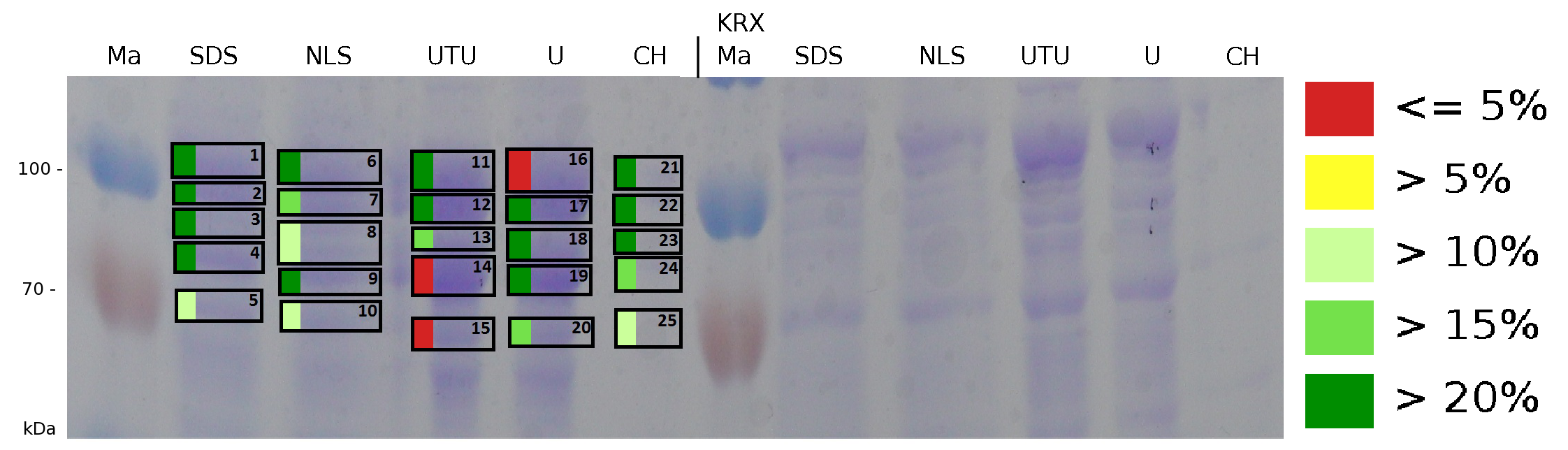

The influence of other detergents to disintegrate the S-layer fusion protein was tested after disrupting the cells with a ribolyser. The cell pellet was incubated in 10 % (v/v) Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), in 7 M urea and 3 M thiourea (UTU), in 10 M urea (U) in 10 % (v/v) n-lauroyl sarcosine (NLS) and in 2 % CHAPS (C). Samples of the incubations with these detergents were loaded onto a SDS-PAGE prior to measurement with MALDI TOF.

The result of the MALDI-TOF measurement clearly demonstrates that all used detergents are applicable to disintegrate the S-layer fusion proteins from the bacterial cell membrane of E. coli. Fluorescence measurement of fractions, treated with the detergents, show significantly different values, indicating that some of the detergents (e.g. 3 M thiourea, 7 M urea) have a strong effect on protein folding.

Methods

Expression of S-layer genes in E. coli

- Chassis: Promega's [http://www.promega.com/products/cloning-and-dna-markers/cloning-tools-and-competent-cells/bacterial-strains-and-competent-cells/single-step-_krx_-competent-cells/ E. coli KRX]

- Medium: LB medium supplemented with 20 mg L-1 chloramphenicol

- For autoinduction: Cultivations in LB-medium were supplemented with 0.1 % L-rhamnose as inducer and 0.05 % glucose

Measuring of mRFP

- Take at least 500 µL sample for each measurement (200 µL is needed for one measurement) so you can perform a repeat determination

- Freeze biological samples at -80 °C for storage, keep cell-free at 4 °C in the dark

- To measure the samples thaw at room temperature and fill 200 µL of each sample in one well of a black, flat bottom 96 well microtiter plate (perform at least a repeat determination)

- Measure the fluorescence in a platereader (we used a [http://www.tecan.com/platform/apps/product/index.asp?MenuID=1812&ID=1916&Menu=1&Item=21.2.10.1 Tecan Infinite® M200 platereader]) with following settings:

- 20 sec orbital shaking (1 mm amplitude with a frequency of 87.6 rpm)

- Measurement mode: Top

- Excitation: 584 nm

- Emission: 620 nm

- Number of reads: 25

- Manual gain: 100

- Integration time: 20 µs

Tryptic digest of gel lanes for analysis with MALDI-TOF

Note:

- Make sure to work under a fume hood.

- Do not work with protective gloves to prevent contamination of your sample with platicizers.

Reaction tubes have to be cleaned with 60% (v/v) CH3CN, 0.1% (v/v) TFA. Afterwards the solution has to be removed completely followed by evaporation of the tubes under a fume hood. Alternatively microtiter plates from Greiner® (REF 650161) can be used without washing.

- Cut out the protein lanes of a Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE using a clean scalpel. Gel parts are transferred to the washed reaction tubes/microtiter plate. If necessary cut the parts to smaller slices.

- Gel slices should be washed two times. Therefore add 200 µL 30% (v/v) acetonitrile in 0.1 M ammonium hydrogen carbonate each time and shake lightly for 10 minutes. Remove supernatant and discard to special waste.

- Dry gel slices at least 30 minutes in a Speedvac.

- Rehydrate gel slices in 15 µL Trypsin-solution followed by short centrifugation.

- Gel slices have to be incubated 30 minutes at room temperature, followed by incubation at 37 °C over night.

- Dry gel slices at least 30 minutes in a Speedvac.

- According to the size of the gel slice, add 5 – 20 µL 50% (v/v) ACN / 0,1% (v/v) TFA.

- Samples can be used for MALDI measurement or stored at -20 °C.

Trypsin-solution: 1 µL Trypsin + 14 µL 10 mM NH4HCO3

- Therefore solubilize lyophilized Trypsin in 200 µL of provided buffer and incubate for 15 minutes at 30 °C for activation. For further use it can be stored at -20 °C.

Preparation and Spotting for analysis of peptides on Bruker AnchorChips

- Spot 0,5 – 1 µL sample aliquot

- Add 1 µL HCCA matrix solution to the spotted sample aliquots. Pipet up and down approximately five times to obtain a sufficient mixing. Be careful not to contact the AnchorChip.

Note: Most of the sample solvent needs to be gone in order to achieve a sufficiently low water content. When the matrix solution is added to the previously spotted sample aliquot at a too high water content in the mixture, it will result in undesired crystallization of the matrix outside the anchor spot area.

- Dry the prepared spots at room temperature

- Spot external calibrants on the adjacent calibrant spot positions. Use the calibrant stock solution (Bruker’s “Peptide Calibration Standard II”, Part number #222570), add 125 µL of 0,1% TFA (v/v) in 30% ACN to the vial. Vortex and sonicate the vial.

- Mix the calibrant stock solution in a 1:200 ratio with HCCA matrix and deposit 1 µL of the mixture onto the calibrant spots.

References

Hansmeier N, Bartels FW, Ros R, Anselmetti D, Tauch A, Pühler A, Kalinowski J (2004) Classification of hyper-variable Corynebacterium glutamicum surface-layer proteins by sequence analyses and atomic force microscopy [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S016816560400241X J Biotechnol. 26;112(1-2):177-93.]