Difference between revisions of "Part:BBa K4365014"

Svetlana ia (Talk | contribs) |

Svetlana ia (Talk | contribs) (→Signal peptide secretion screening) |

||

| Line 89: | Line 89: | ||

The first secretion experiment was conducted in flasks and showed (Figure 2A) that cell lysis was low as indicated by the low fluorescence of the negative control. In order to have consistent results and ensure confidence we set up biological triplicates. For this, turboRFP secretion was measured using 48-well plate approach. Cells with induced expression were pipetted into the wells of the plate and grown overnight. Starting at 1 hour after induction, samples were taken and the growth rate was monitored by measuring turbidity (NTU) and the development of fluorescence in the supernatant was measured on a plate reader. | The first secretion experiment was conducted in flasks and showed (Figure 2A) that cell lysis was low as indicated by the low fluorescence of the negative control. In order to have consistent results and ensure confidence we set up biological triplicates. For this, turboRFP secretion was measured using 48-well plate approach. Cells with induced expression were pipetted into the wells of the plate and grown overnight. Starting at 1 hour after induction, samples were taken and the growth rate was monitored by measuring turbidity (NTU) and the development of fluorescence in the supernatant was measured on a plate reader. | ||

| − | Despite the unstable secretion behaviour in a flask experiment (Figure 2A), turboRFP secretion measurements obtained by a more sensitive | + | Despite the unstable secretion behaviour in a flask experiment (Figure 2A), turboRFP secretion measurements obtained by a more sensitive approach showed some secretion in ''S. cerevisiae'' (Figure 2B). This shows that K4365014-turboRFP could be secreted from ''S. cerevisiae''. |

<!--This part different between sps--> | <!--This part different between sps--> | ||

Latest revision as of 22:35, 11 October 2022

Signal peptide of ABH3 from Agaricus bisporus

ABH3 is a protein found in Agaricus bisporus and belongs to a family of highly secreted proteins called hydrophobins. The signal peptide from the protein led to turboRFP secretion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

| ID | Source | Species | Prediction coefficient [1] | turboRFP secretion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sp1 | BBa_K4365006 | MPGI | Magnaporthe grisea | 0.9562 | Yes |

| sp2 | BBa_K4365007 | RodA | Aspergillus nidulans | 0.9553 | Yes |

| sp3 | BBa_K4365008 | HYPI | Aspergillus fumigatus | 0.9703 | No |

| sp4 | BBa_K4365009 | SsgA | Metarhizium anisopliae | 0.9126 | No |

| sp5 | BBa_K4365010 | HCF-4 | Cladosporium fulvum | 0.9126 | Yes |

| sp6 | BBa_K4365025 | HCF-5 | Cladosporium fulvum | 0.9234 | NA |

| sp7 | BBa_K4365026 | CCG-2 | Neurospora crassa | 0.9566 | NA |

| sp8 | BBa_K4365011 | HCF-1 | Cladosporium fulvum | 0.6850 | Yes |

| sp9 | BBa_K4365027 | HCF-2 | Cladosporium fulvum | 0.8144 | NA |

| sp10 | BBa_K4365012 | HCF-3 | Cladosporium fulvum | 0.7934 | No |

| sp11 | BBa_K4365013 | SC3 | Schizophyllum commune | 0.6327 | No |

| sp12 | BBa_K4365014 | ABH3 | Agaricus bisporus | 0.9458 | Yes |

| sp13 | BBa_K4365028 | COH1 | Coprinus cinereus | 0.8545 | NA |

| sp14 | BBa_K4365015 | FBH1 | Pleurotus ostreatus | 0.3367 | Yes |

| sp15 | BBa_K4365016 | Aa-PRI2 | Agrocybe aegerita | 0.6356 | Yes |

| sp16 | BBa_K4365033 | Hyd-Pt1 | Pisolithus tinctorius | 0.8352 | NA |

| sp17 | BBa_K4365017 | HFBI | Trichoderma reesei | 0.9851 | Yes |

| sp18 | BBa_K4365018 | HFBII | Trichoderma reesei | 0.6862 | Yes |

| sp19 | BBa_K4365019 | α-mating factor | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 0.9988 | Yes |

- ↑ José Juan Almagro Armenteros et al. (2019) SignalP 5.0 improves signal peptide predictions using deep neural networks Nature Biotechnology, 37, 420-423, doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0036-z

Sequence and Features

- 10COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[10]

- 12COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[12]

- 21COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[21]

- 23COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[23]

- 25COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[25]

- 1000COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[1000]

Usage and Biology

Secretion signal peptides can be fused to a protein to direct it through the secretory pathway out of the cell [1]. Such secretion of recombinant proteins facilitates the protein purification process and the removal of GMOs [2]. However, commonly used signal sequences like the S. cerevisiae alpha-factor prepro-peptide K4365019 and the HSP150, are very long [2][3] which makes their use in genetic constructs limited. K4365014 as a part of the collection of signal peptides represents a shorter sequence that could be inserted into the gene of interest simply by PCR and could display higher secretion efficiency.

The sequences of the hydrophobic signal peptide was collected from literature [4] and was extracted via analysis of their sequence using the SignalP - 5.0 signal peptide predictor tool [5].

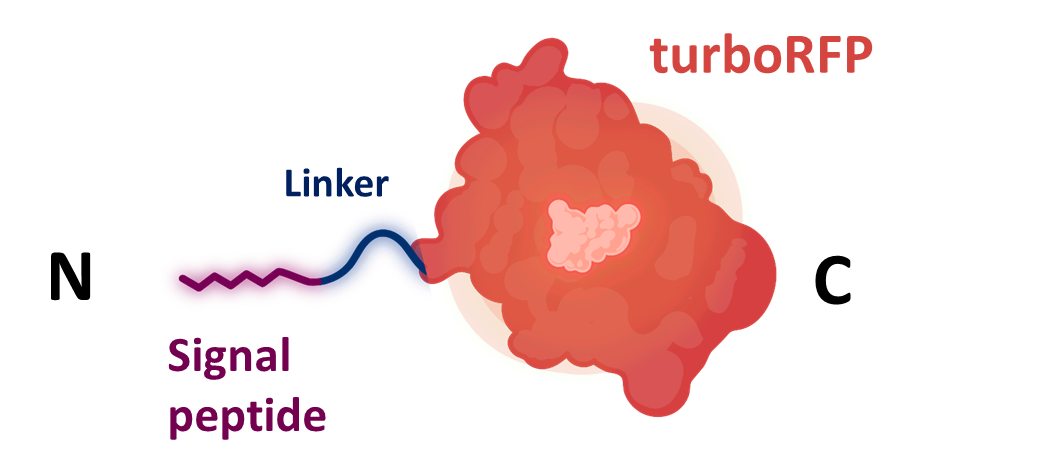

Identified sequence was codon-optimized for S. cerevisiae using the codon optimization tool on GenScript. Then it was synthesized by IDT as a gBlock together with a flexible glycine linker (K4365005) and the turboRFP gene (K4365020) [6].

Hydrophobins

Hydrophobins are a group of small (~100 amino acids) proteins that are expressed in ascomycetes and basidiomycetes, which are very efficiently secreted [2].

After secretion from the fungus, they can assemble on the cell walls to form a hydrophobic coating. For this reason, the functions of hydrophobins are related to cell surface activity. For example, they can cover hyphae so the surface tension can be lowered and the hyphae can breach the water/air interface, thus escaping from the aqueous environment and growing into the aerial hyphae [7]. They also mediate the adhesion of the hyphae to hydrophobic surfaces such as in the case of pathogen-host interaction or symbiosis, as observed in lichens and in ectomycorrhizae (the symbiotic relationship between a fungal symbiont and the roots of a plant) [7]. Hydrophobins also form a hydrophobic sheath to protect the surface of conidia, spores, and caps of fungi against wetting and desiccation [7].

Signal peptide secretion screening

Signal peptide siquence was cloned together with turboRFP K4365020 into the level 1 shuttle plasmid K4365022 (Figure 1).

After the transformation with the shuttle plasmid, the yeast colonies were grown on W0 medium plates supplemented with histidine, leucine, and methionine and were used for secretion assays in flasks and in a 48-well plate. The α-mating factor pre-pro signal peptide K4365019 was used as a positive control as it has been shown to be able to secrete proteins [8]. A turboRFP without signal peptide was employed as a negative control to account for the amount of free turboRFP present in the media due to cell lysis.

Secretion measurement protocols:

The first secretion experiment was conducted in flasks and showed (Figure 2A) that cell lysis was low as indicated by the low fluorescence of the negative control. In order to have consistent results and ensure confidence we set up biological triplicates. For this, turboRFP secretion was measured using 48-well plate approach. Cells with induced expression were pipetted into the wells of the plate and grown overnight. Starting at 1 hour after induction, samples were taken and the growth rate was monitored by measuring turbidity (NTU) and the development of fluorescence in the supernatant was measured on a plate reader.

Despite the unstable secretion behaviour in a flask experiment (Figure 2A), turboRFP secretion measurements obtained by a more sensitive approach showed some secretion in S. cerevisiae (Figure 2B). This shows that K4365014-turboRFP could be secreted from S. cerevisiae.

References

- ↑ Alberts, B. (2015) Molecular Biology of the Cell. 6th Edition, Garland Science, Taylor and Francis Group, New York.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Kirsten Kottmeier, Kai Ostermann, Thomas Bley, Gerhard Rödel (2011) Hydrophobin signal sequence mediates efficient secretion of recombinant proteins in Pichia pastoris, Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 91, pages133–141, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-011-3246-y

- ↑ Russo P, Kalkkinen N, Sareneva H, Paakkola J, Makarow M. A heat shock gene from Saccharomyces cerevisiae encoding a secretory glycoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 May 1;89(9):3671-5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.3671. Erratum in: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Sep 15;89(18):8857. PMID: 1570286; PMCID: PMC525552.

- ↑ Sigridur A. Ásgeirsdóttir, John R. Halsall, Lorna A. Casselton (1997) Expression of Two Closely Linked Hydrophobin Genes ofCoprinus cinereusIs Monokaryon-Specific and Down-Regulated by theoid1Mutation, Fungal Genetics and Biology Volume 22, Issue 1, Pages 54-63, https://doi.org/10.1006/fgbi.1997.0992

- ↑ José Juan Almagro Armenteros et al. (2019) SignalP 5.0 improves signal peptide predictions using deep neural networks Nature Biotechnology, 37, 420-423, doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0036-z

- ↑ Merzlyak, E., Goedhart, J., Shcherbo, D. et al. (2007) Bright monomeric red fluorescent protein with an extended fluorescence lifetime. Nat Methods 4, 555–557 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth1062

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Khalesi, M., Gebruers, K. & Derdelinckx, G. (2015) Recent Advances in Fungal Hydrophobin Towards Using in Industry, Protein J, 34, 243–255 . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10930-015-9621-2

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Peñas M. M. et al. (1998) Identification, characterization, and In situ detection of a fruit-body-specific hydrophobin of Pleurotus ostreatus, Appl Environ Microbiol. 64(10):4028-34. doi: 10.1128/AEM.64.10.4028-4034.1998. PMID: 9758836; PMCID: PMC106595.