Difference between revisions of "Part:BBa K1907000"

(→Contribution: TecMonterrey_GDL (2022)) |

(→Contribution: TecMonterrey_GDL (2022)) |

||

| (36 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

Shaner, N.C., Steinbach, P.A. and Tsien, R.Y., 2005. A guide to choosing fluorescent proteins. Nature methods, 2(12), pp.905-909. | Shaner, N.C., Steinbach, P.A. and Tsien, R.Y., 2005. A guide to choosing fluorescent proteins. Nature methods, 2(12), pp.905-909. | ||

| − | + | =Contribution: TecMonterrey_GDL (2022)= | |

| + | __TOC__ | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div style="text-align:justify;"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Generation of an improved variant of Venus=== | ||

| + | <div style="text-align:justify;"> | ||

Enhanced fluorescent proteins can be widely used to track the localization and dynamics of proteins, organelles, and other cellular compartments, as well as a tracer of intracellular protein trafficking. However, mutagenesis has provoked an assortment of visible fluorescent proteins, and besides mutations that influence spectral properties, numerous modifications have been described that enhance the brightness of one or more visible fluorescent protein variants. | Enhanced fluorescent proteins can be widely used to track the localization and dynamics of proteins, organelles, and other cellular compartments, as well as a tracer of intracellular protein trafficking. However, mutagenesis has provoked an assortment of visible fluorescent proteins, and besides mutations that influence spectral properties, numerous modifications have been described that enhance the brightness of one or more visible fluorescent protein variants. | ||

| − | In this contribution, the effects of a particular mutation in the yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) enhanced variant, Venus, are described according to what was reported by Kremers et al. (2006). Venus is an essential (constitutively fluorescent) yellow fluorescent protein firstly characterized in 2002, derived from Aequorea victoria (Nagai et al., 2002). Among its characteristics, Venus contains a novel mutation, F46L, folding relatively well and acquiring tolerance to exposure to acidosis and chloride ions. | + | In this contribution, the effects of a particular mutation in the yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) enhanced variant, Venus, are described according to what was reported by Kremers <i>et al.</i> (2006). Venus is an essential (constitutively fluorescent) yellow fluorescent protein firstly characterized in 2002, derived from <i>Aequorea victoria</i> (Nagai et al., 2002). Among its characteristics, Venus contains a novel mutation, F46L, folding relatively well and acquiring tolerance to exposure to acidosis and chloride ions, compared to other yellow fluorescent proteins. |

| + | |||

| + | Nevertheless, Kremers <i>et al.</i> (2006) report the results of a site-directed mutagenesis approach to improve Venus's thermosensitivity, and dim fluoresce through the folding mutation A206K, named as mVenus. According to Zacharias <i>et al.</i> (2002), A206K has been described to abolish the tendency of YFP to dimerize. To compare a variety of mutations, Kremers <i>et al.</i> (2006) measured the time course of fluorescence development in <i>Escherichia coli</i> cultures expressing Venus’s variants as GST-tagged fusion proteins at 37 °C. The growth rate of all cultures was similar; therefore, no correction for bacterial growth was required. Results obtained by Kremers <i>et al.</i> (2006) are shown in the following image: | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Contribution_TecMonterreyGDL.jpeg|300px|center|thumb|<b>Figure 1</b>. Expression of GST-tagged YFP variants in E. coli at 37 °C. EYFP(Q69K)(○), Venus(□), mVenus (▲), and SYFP2 (⧫).]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to what is stated in <b>Figure 1</b>, Kremers <i>et al.</i> (2006) state that A206K greatly improved protein folding and solubility and enabled more protein to become fluorescent compared to the original Venus. Moreover, A206K variant or mVenus, reduces the aggregation of yellow fluorescent GST-fusion proteins. For instance, we recommend using <b>mVenus</b> variant for following fluorescent applications, such as dual imaging or fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) sensors. Next, we present the three-dimensional structure of mVenus generated by AlphaFold2 using MMSeqs2 (Mirdita et al., 2022). This structure is as follows: | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:MVenusFinal_TecMonterreyGDL.jpeg|300px|center|thumb|<b>Figure 2</b>. Three-dimensional structure of mVenus.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===References=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | [1]. Kremers, G. J., Goedhart, J., van Munster, E. B., & Gadella, T. W., Jr (2006). Cyan and yellow super fluorescent proteins with improved brightness, protein folding, and FRET Förster radius. <i>Biochemistry, 45</i>(21), 6570–6580. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi0516273 | ||

| + | |||

| + | [2]. Mirdita, M., Schütze, K., Moriwaki, Y. et al. ColabFold: making protein folding accessible to all. <i>Nat Methods 19</i>, 679–682 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-022-01488-1 | ||

| − | + | [3]. Nagai, T., Ibata, K., Park, E. S., Kubota, M., Mikoshiba, K., & Miyawaki, A. (2002). A variant of yellow fluorescent protein with fast and efficient maturation for cell-biological applications. <i>Nature biotechnology</i>, 20(1), 87–90. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt0102-87 | |

| − | + | [4]. Zacharias, D. A., Violin, J. D., Newton, A. C., & Tsien, R. Y. (2002). Partitioning of lipid-modified monomeric GFPs into membrane microdomains of live cells. <i>Science (New York, N.Y.), 296</i>(5569), 913–916. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1068539 | |

| − | |||

Latest revision as of 01:07, 27 September 2022

Venus Yellow Fluorescent Protein

Introduction

Venus yellow fluorescent protein from Aequorea victoria (Nagai et al., 2002), codon-optimized for expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The sequence is just the standalone protein, suitable for use as a fluorescent reporter. To use the part a fluorescent tag fused to another protein domain, it is recommended to add a linker.

Venus has an excitation wavelength of 515 nm and emission wavelength of 528 nm (Shaner et al., 2005). Venus has the advantage over many other YFPs of being less sensitive to environmental factors such as pH and chloride ions, and has a quicker rate of maturation (Nagai et al., 2002).

Sequence and Features

- 10COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[10]

- 12COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[12]

- 21COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[21]

- 23COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[23]

- 25COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[25]

- 1000INCOMPATIBLE WITH RFC[1000]Illegal BsaI.rc site found at 644

Previous use

The part has been expressed in S. cerevisiae strains W303α and SS328-leu, in the pRS415 plasmid under GPD1 and GAL1 promoters. During use, the part has not been used within the context of the BioBricks standard prefix and suffix; instead, the part has been directly flanked by SpeI and XhoI restriction sites (5’ and 3’, respectively), which were also used for cloning into the pRS415 plasmid. Expression results may vary when using the part in a different context; in particular, using the part in the context of the BioBricks prefix results in a T in the -3 position upstream of the start codon, which is strongly disfavored in eukaryotic transcription initiation (Kozak, 1996; Cavener et al., 1991).

Expression

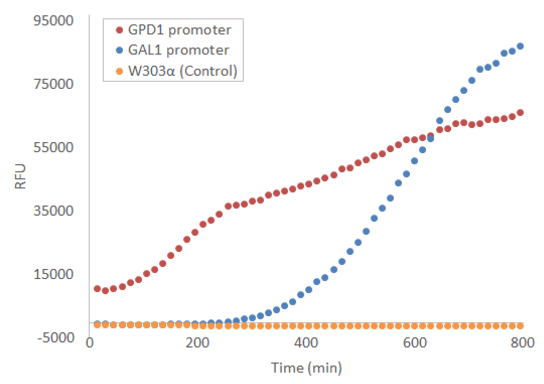

When used in the pRS415 plasmid, the produced fluorescence is not visible by eye, but can be easily measured with e.g. a microplate reader. Figure 1 presents the development of fluorescence under GPD1 and GAL1 promoters over time when a culture of starting OD=0.5 is grown at +30 °C with linear shaking of 731 cpm. Galactose induction is performed at t = 0.

For more details on the experiments done with this BioBrick, visit http://2016.igem.org/Team:Aalto-Helsinki/Laboratory

References

Cavener, D.R., Ray, S.C, 1991. Eukaryotic start and stop translation sites. Nucleic Acids Research, 1991, 19(12), pp. 3185-3192

Kozak, M., 1996 Point mutations define a sequence flanking the AUG initiator codon that modulates translation by eukaryotic ribosomes. Cell, 44(2), pp. 283-292

Nagai, T., Ibata, K., Park, E.S., Kubota, M., Mikoshiba, K., Atsushi, M., 2002, A variant of yellow fluorescent protein with fast and efficient maturation for cell-biological applications, Nature Biotechnology, 20(1), pp. 87-90

Shaner, N.C., Steinbach, P.A. and Tsien, R.Y., 2005. A guide to choosing fluorescent proteins. Nature methods, 2(12), pp.905-909.

Contribution: TecMonterrey_GDL (2022)

Contents

Generation of an improved variant of Venus

Enhanced fluorescent proteins can be widely used to track the localization and dynamics of proteins, organelles, and other cellular compartments, as well as a tracer of intracellular protein trafficking. However, mutagenesis has provoked an assortment of visible fluorescent proteins, and besides mutations that influence spectral properties, numerous modifications have been described that enhance the brightness of one or more visible fluorescent protein variants.

In this contribution, the effects of a particular mutation in the yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) enhanced variant, Venus, are described according to what was reported by Kremers et al. (2006). Venus is an essential (constitutively fluorescent) yellow fluorescent protein firstly characterized in 2002, derived from Aequorea victoria (Nagai et al., 2002). Among its characteristics, Venus contains a novel mutation, F46L, folding relatively well and acquiring tolerance to exposure to acidosis and chloride ions, compared to other yellow fluorescent proteins.

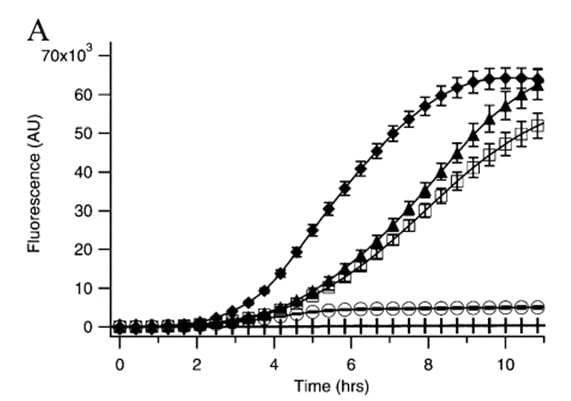

Nevertheless, Kremers et al. (2006) report the results of a site-directed mutagenesis approach to improve Venus's thermosensitivity, and dim fluoresce through the folding mutation A206K, named as mVenus. According to Zacharias et al. (2002), A206K has been described to abolish the tendency of YFP to dimerize. To compare a variety of mutations, Kremers et al. (2006) measured the time course of fluorescence development in Escherichia coli cultures expressing Venus’s variants as GST-tagged fusion proteins at 37 °C. The growth rate of all cultures was similar; therefore, no correction for bacterial growth was required. Results obtained by Kremers et al. (2006) are shown in the following image:

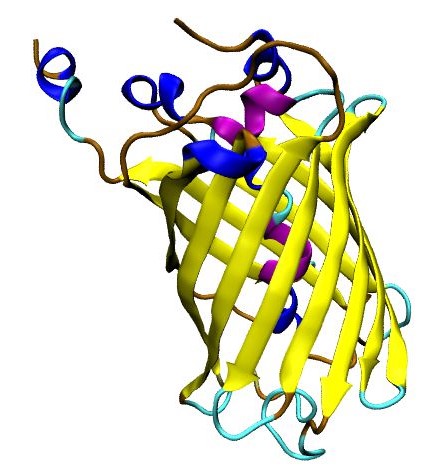

According to what is stated in Figure 1, Kremers et al. (2006) state that A206K greatly improved protein folding and solubility and enabled more protein to become fluorescent compared to the original Venus. Moreover, A206K variant or mVenus, reduces the aggregation of yellow fluorescent GST-fusion proteins. For instance, we recommend using mVenus variant for following fluorescent applications, such as dual imaging or fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) sensors. Next, we present the three-dimensional structure of mVenus generated by AlphaFold2 using MMSeqs2 (Mirdita et al., 2022). This structure is as follows:

References

[1]. Kremers, G. J., Goedhart, J., van Munster, E. B., & Gadella, T. W., Jr (2006). Cyan and yellow super fluorescent proteins with improved brightness, protein folding, and FRET Förster radius. Biochemistry, 45(21), 6570–6580. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi0516273

[2]. Mirdita, M., Schütze, K., Moriwaki, Y. et al. ColabFold: making protein folding accessible to all. Nat Methods 19, 679–682 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-022-01488-1

[3]. Nagai, T., Ibata, K., Park, E. S., Kubota, M., Mikoshiba, K., & Miyawaki, A. (2002). A variant of yellow fluorescent protein with fast and efficient maturation for cell-biological applications. Nature biotechnology, 20(1), 87–90. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt0102-87

[4]. Zacharias, D. A., Violin, J. D., Newton, A. C., & Tsien, R. Y. (2002). Partitioning of lipid-modified monomeric GFPs into membrane microdomains of live cells. Science (New York, N.Y.), 296(5569), 913–916. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1068539