|

|

| (17 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) |

| Line 37: |

Line 37: |

| | __NOTOC__ | | __NOTOC__ |

| | <partinfo>BBa_K3228069 short</partinfo> | | <partinfo>BBa_K3228069 short</partinfo> |

| | + | |

| | + | ===Sequence and Features=== |

| | + | <partinfo>BBa_K3228069 SequenceAndFeatures</partinfo> |

| | + | |

| | + | ===B A S I C P A R T S=== |

| | + | |

| | + | <html> |

| | + | <h4>Cyanobacterial shuttle vectors </h4> |

| | + | |

| | + | As we have already clarified in the description part, self replicating shuttle vectors are essential for many |

| | + | workflows, as the gene expression levels are higher and non of the tedious selection processes that come with |

| | + | genomic integrations have to be done. <br> |

| | + | |

| | + | On our road to the modular vector we were seeking, we firstly cured our own S. elongatus UTEX 2973 strain of its |

| | + | pANS plasmid. This was done by transforming the pAM4787 vector, which holds a spectinomycin resistance as well as a |

| | + | YFP cassette |

| | + | <a href= https://www.microbiologyresearch.org/content/journal/micro/10.1099/mic.0.000377> (Chen et al., 2016)</a>. |

| | + | Due to plasmid incompatibility - explained here in our design section <b>[Link to shuttle vector design]</b> - and because antibiotic pressure is applied, the pANS plasmid was over time cured from the |

| | + | strain, which then just kept the pAM4787 plasmid. Transformation was done by conjugation with the pRK2013 plasmid in |

| | + | DH5ɑ and the pAM4787 in HB101. Both were grown to an OD600≈0.5, washed in LB and mixed with S. elongatus which was |

| | + | grown to late exponential phase and then washed in BG11. |

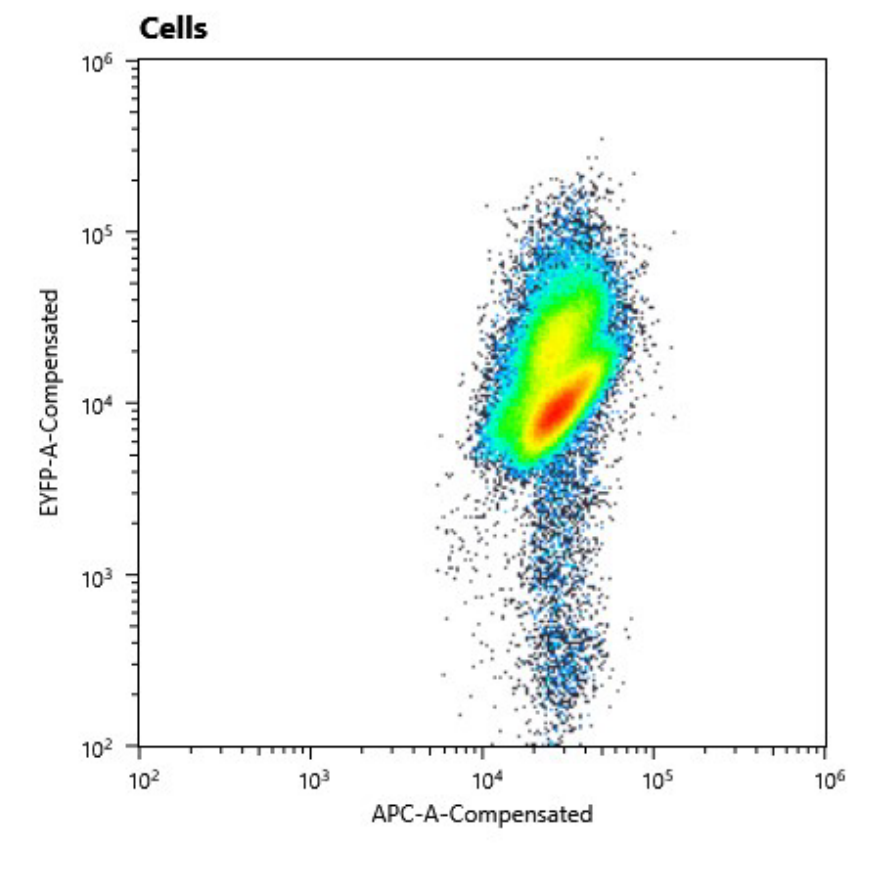

| | + | We could clearly show, that the conjugant strain bears the pAM4787 plasmid if selective pressure is held up. |

| | + | <figure Style="text-align:center"> |

| | + | <img style="height: 65ex; width: 50ex" |

| | + | src= https://2019.igem.org/wiki/images/e/eb/T--Marburg--YFPconstructConjugantFACS.png |

| | + | alt=" https://2019.igem.org/wiki/images/e/eb/T--Marburg--YFPconstructConjugantFACS.png"> |

| | + | <figcaption> |

| | + | Fig. 11: Cell counts of conjugant strain. The y axis shows relative YFP fluorescence and the x axis relative autofluorescence. |

| | + | </figcaption> |

| | + | </figure> |

| | + | This was followed by us starting to culture the pAM4787 bearing strain without |

| | + | antibiotics again, slowly removing selective pressure from the cells. As the plasmid does not give them any other |

| | + | advantage and is probably just more metabolic burden due to the constantly produced YFP proteins it is slowly being |

| | + | lost. |

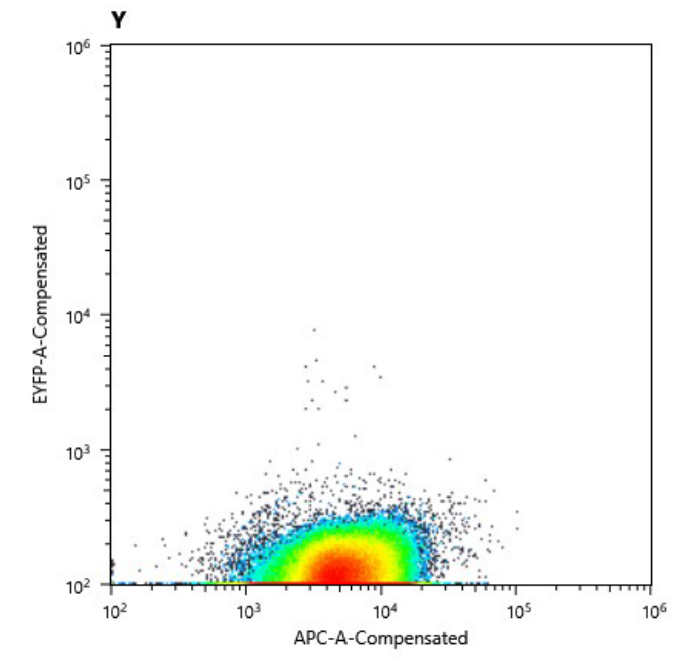

| | + | We could prove this in multiple setups: with the flow cytometry device we were kindly granted access to we could |

| | + | clearly show the missing YFP signal in the cured <i>S. elongatus </i>strain and |

| | + | logically this could also be observed over our UV table |

| | + | |

| | + | <figure Style="text-align:center"> |

| | + | <img style="height: 65ex; width: 50ex" |

| | + | src= https://2019.igem.org/wiki/images/c/c4/T--Marburg--CuredStrainsFACS.png |

| | + | alt="https://2019.igem.org/wiki/images/c/c4/T--Marburg--CuredStrainsFACS.png "> |

| | + | <img style="height: 65ex; width: 50ex" |

| | + | src= https://2019.igem.org/wiki/images/d/da/T--Marburg--CuredStrainUV.png |

| | + | alt="https://2019.igem.org/wiki/images/d/da/T--Marburg--CuredStrainUV.png"> |

| | + | <figcaption> |

| | + | a) Cell counts of cured strain. The y axis shows relative YFP fluorescence and the x axis relative autofluorescence |

| | + | b) Comparison of the fluorescence signal of the transformed (left) and cured (right) strain. |

| | + | </figcaption> </figure> |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

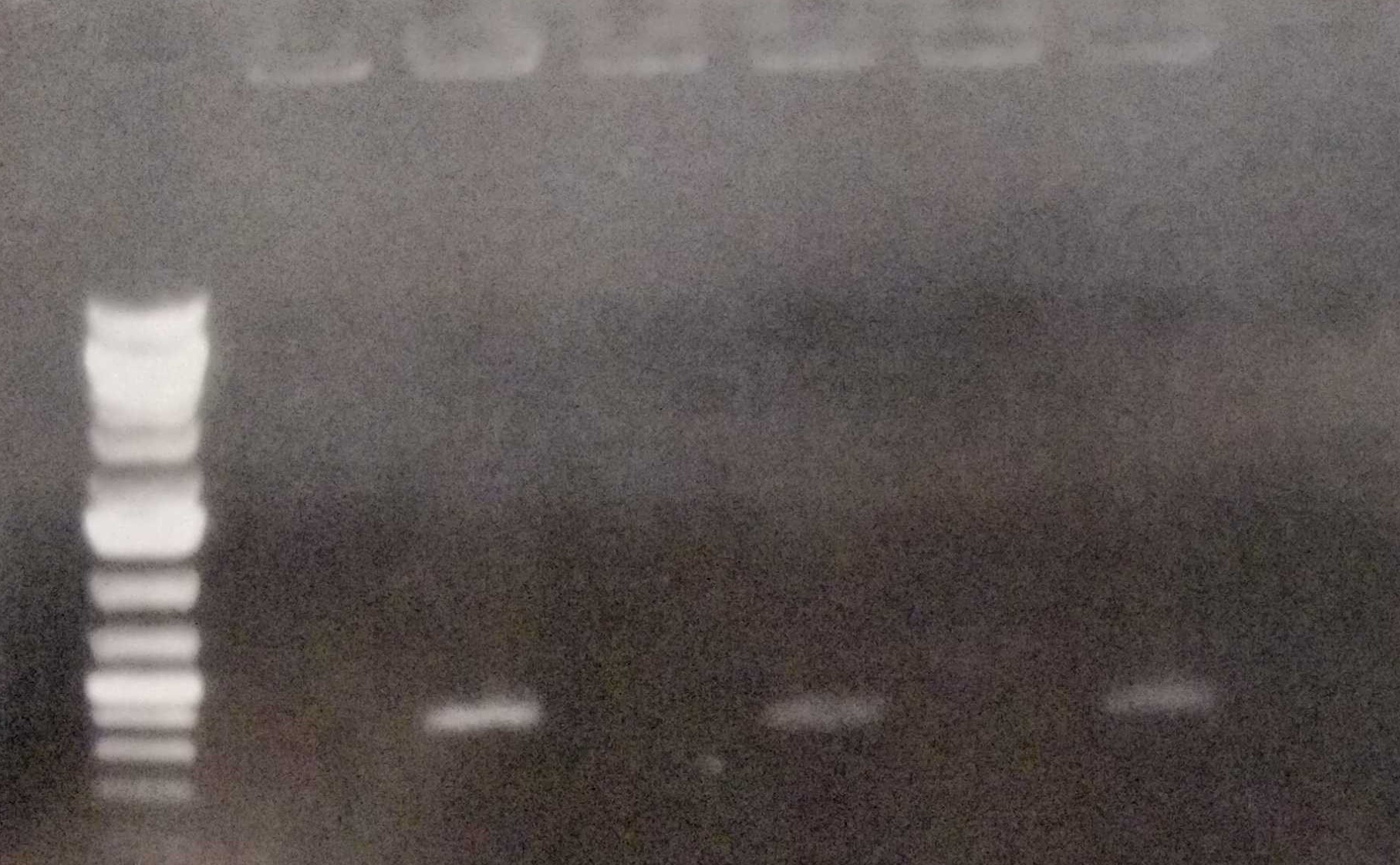

| | + | Furthermore we performed colony PCRs as a test. We sent our plasmid-free strain to Next Generation Sequencing in order to ensure that the strain really has lost the |

| | + | pANS plasmid. |

| | + | <figure Style="text-align:center"> |

| | + | <img style="height: 65ex; width: 50ex" |

| | + | src= https://2019.igem.org/wiki/images/e/e9/T--Marburg--ColonyPCRcuredStrain.jpg |

| | + | alt="gel pcr"> |

| | + | <figcaption> Fig. 12: Colony PCR of the wild type, the conjugated and the cured strain. |

| | + | </figcaption> |

| | + | </figure> |

| | + | |

| | + | Our next step was the characterization of the cyanobacterial shuttle vector mentioned in our design section <b>[Link to |

| | + | design]</b>. |

| | + | In an extensive flow cytometry experiment we assessed the fluorescence of a transformed YFP-construct in our cured |

| | + | strain, showing that the shuttle vector with the minimal replication element can be maintained in<i>S. elongatus </i> UTEX |

| | + | 2973 . |

| | + | <figure Style="text-align:center"> |

| | + | <img style="height: 65ex; width: 50ex" |

| | + | src= |

| | + | alt="hier kommen noch 3 bilder von FACS Messung aber no time"> |

| | + | <figcaption> Fig. 13: hier kommen noch 3 bilder von FACS Messung aber no time. |

| | + | </figcaption> |

| | + | </figure> |

| | + | After another four weeks of cultivation we looked at our |

| | + | cultures again on the UV table to check if fluorescence was still present and the high intensity of the fluorescence |

| | + | proved to us, that the plasmid is still stably replicated in our strain, showing us, that the minimal replication |

| | + | element does indeed work in our strain. |

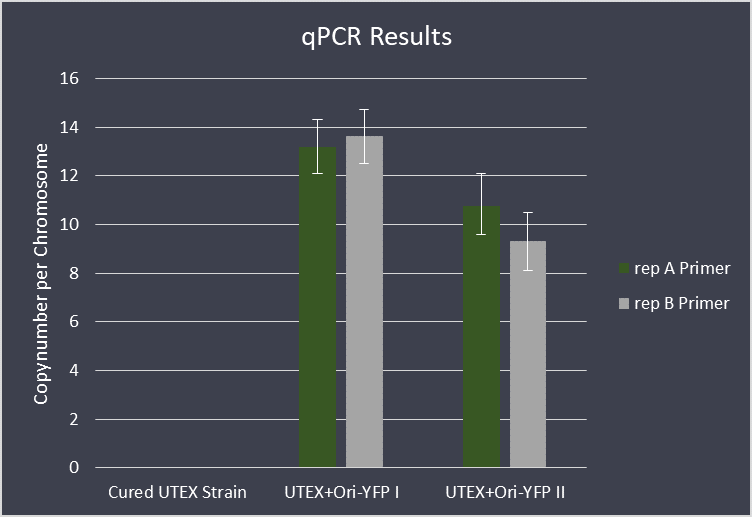

| | + | For further analysis we performed qPCR with this transformed strain, in order to check the copy number of the |

| | + | vector. We used the copy number of pANL as a reference, which is supposedly at ~2,6 copies per chromosome |

| | + | <a href= https://www.microbiologyresearch.org/content/journal/micro/10.1099/mic.0.000377> (Chen et al., 2016)</a>. Our data shows a ~4,5 times higher copy number relative to pANL, meaning that the construct is |

| | + | maintained with approximately 11,7 copies per chromosome. |

| | + | <figure Style="text-align:center"> |

| | + | <img style="height: 65ex; width: 50ex" |

| | + | src="https://2019.igem.org/wiki/images/d/d6/T--Marburg--Parts--qPCR-Lvl1.png" |

| | + | alt="Copynumber Evaluation of Ori-part via qPCR"> |

| | + | <figcaption> Fig. 14: Copynumber Evaluation of Ori-part via qPCR |

| | + | </figcaption> |

| | + | </figure> |

| | + | |

| | + | |

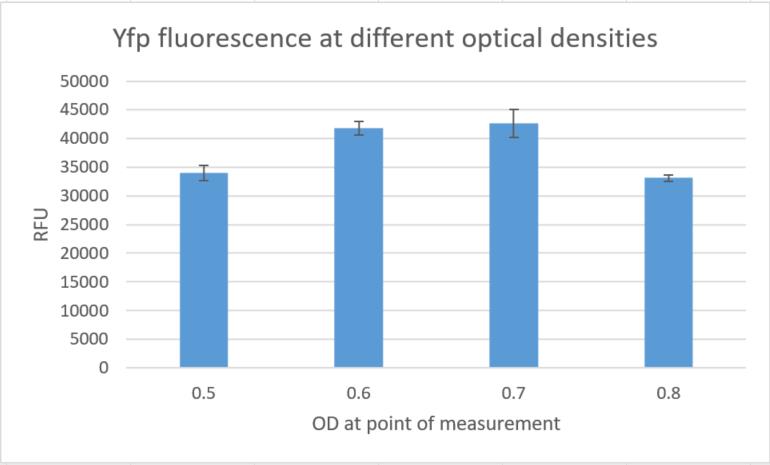

| | + | Additionally we measured the fluorescence signals in a plate reader at different optical densities and could again |

| | + | confirm high fluorescence signals, indicating strong gene expression in constructs built around this replication |

| | + | element. |

| | + | <figure Style="text-align:center"> |

| | + | <img style="height: 65ex; width: 50ex" |

| | + | src= https://2019.igem.org/wiki/images/f/f0/T--Marburg--results_yfp_pam_4787_6_replicates.jpg |

| | + | alt="diagramm"> |

| | + | <figcaption> Fig. 15:YFP fluorescence at different optical densities. </figcaption> |

| | + | </figure> |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | All this data confirms that the construct actually works and can be reliably used as a cyanobacterial shuttle |

| | + | vector, proving that BBa_K3228069 works as intended, thus functioning as our validated part. |

| | + | This assumption is solidified by all our sequence data, showing that the shuttle vectors were completely assembled |

| | + | as planned in our design section <b>[Link to design of shuttle vectors]</b> |

| | + | . |

| | + | <figure Style="text-align:center"> |

| | + | <img style="height: 65ex; width: 50ex" |

| | + | src= xyz |

| | + | alt="disgramm"> |

| | + | <figcaption> Fig. 16: [FigXX seq results of lvl1 and lvl2 ori] </figcaption> |

| | + | </figure> |

| | + | </p> |

| | + | |

| | + | </p> |

| | + | </html> |

| | <html> | | <html> |

| | <p align="justify"> | | <p align="justify"> |

| | | | |

| − | This is the Phytobrick version of the Connector 5'Connector Dummy and was build as a part of the Marburg Collection. Instructions of how to use the Marburg Collection are provided at the bottom of the page. | + | This part is contained in the Green Expansion, a range of parts from <a href="https://2019.igem.org/Team:Marburg">iGEM Marburg 2019</a>that enables users of the Marburg Collection 2.0 to design MoClo compatible vectors for cyanobacteria as well as to engineer the genome of several cyanobacterial species. |

| | | | |

| | </p> | | </p> |

| | </html> | | </html> |

| | | | |

| − | ===Overview=== | + | ===The Green Expansion=== |

| | | | |

| | <html> | | <html> |

| | <p align="justify"> | | <p align="justify"> |

| | | | |

| − | One novel key feature of our toolbox are the connectors. They were designed in order to function as insulators to prevent crosstalk between neighboring transcription units <a href="http://2018.igem.org/Team:Marburg/Design">(Design of the Marburg Collection)</a>. Therefore a perfectly insulating connector would prevent the readthrough from backbone sequences that most probably caused the notably high expression that was measured in the promoter experiment for the dummy promoter <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560007#Characterization">(Promoter experiment)</a>. In addition to blocking transcriptional readthrough, a good connector must not possess any cryptic promoter activity.

| + | The Green Expansion is an addition of parts to the Marburg Collection 2.0 <a href="http://2018.igem.org/Team:Marburg/Design">(See: Design of the Marburg Collection)</a> that features the world's first MoClo compatible shuttle vector for cyanobacteria. <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228069">BBa_K3228069</a> |

| − | <br>

| + | |

| − | <br>

| + | |

| − | In already existing toolboxes, the combinatorics that come with choosing oris and resistances would be multiplied by the number of required positional vectors which provide the fusion sites for LVL2 assembly. A toolbox with five possible positions, four resistances and three oris would require 60 LVL1 destination plasmids. To enable inversion of transcription units, a built-in feature in our toolbox, the previous number would be multiplied by two, resulting in 120 required LVL1 destination plasmids. Unsurprisingly, this theoretical toolbox would not be convenient to be built and used.

| + | |

| − | <br>

| + | |

| − | <br>

| + | |

| − | The Marburg Collection presents a novel approach that achieves maximum flexibility with a minimum of required components (figure 1).

| + | |

| | </html> | | </html> |

| | | | |

| | <div style="width:100%;display:flex;flex-direction:row;flex-wrap: wrap; justify-content:space-evenly; align-items:center;"> | | <div style="width:100%;display:flex;flex-direction:row;flex-wrap: wrap; justify-content:space-evenly; align-items:center;"> |

| | | | |

| − | [[File:T--Marburg--Default_Connectors.png|500px|thumb|left|'''Figure 1''': <b> Default setup of connectors for building a LVL2 plasmid consisting of 5 transcription units. </b> <br> The connectors match in the following pattern: 5'Con(N) connects to 3'Con(N-1) .]] | + | [[File:GE LVL1 ori.png|500px|thumb|left|'''Figure 1''': Design of the first MoClo compatible shuttle vector for cyanobacteria for LVL 1 constructs. This can be used for the integration of simple genetic modules. ]] |

| | | | |

| | </div style> | | </div style> |

| | | | |

| − | We provide two sets of connectors. The first set, the “short connectors” solely provide the fusion sites for subsequent assembly. The fusion sites are identical to the ones that are used in building LVL1 plasmids to avoid having to design a complete new set of fusion sites. This also enables using LVL0 ori and resistance parts in LVL2 plasmids. Inversion of individual transcription units was also achieved by designing fusion sites that match in reverse order.

| |

| | | | |

| | <div style="width:100%;display:flex;flex-direction:row;flex-wrap: wrap; justify-content:space-evenly; align-items:center;"> | | <div style="width:100%;display:flex;flex-direction:row;flex-wrap: wrap; justify-content:space-evenly; align-items:center;"> |

| | | | |

| − | [[File:T--Marburg--Connector_inversed.png|600px|thumb|left|'''Figure 2''': <b>Inversion of transcription units is feasible with our connectors. </b> <br> To achieve inversion, the respective transcription unit has to be built with connectors that match the neighboring transcription units. The function by following pattern: 3'Con(N)inv connects to 3'Con(N-1) and 5'Con(N)inv connects to 5'Con(N+1)]] | + | [[File:GE LVL2 ori.png|500px|thumb|left|'''Figure 2''': Design of the first MoClo compatible shuttle vector for cyanobacteria for LVL 2 constructs. This can be used for the integration of complex genetic devices. ]] |

| | | | |

| | </div style> | | </div style> |

| − |

| |

| | | | |

| | <html> | | <html> |

| − | The 5’ and 3’ connectors can be chosen independently to build a LVL1 plasmid. This allows the user to combine any number of LVL1 plasmids between one and five into a LVL2 plasmid without end linkers that are required in other toolboxes <a href="https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0189892"><abbr title="Mobius Assembly: A versatile Golden-Gate framework towards universal DNA assembly">(Andreou and Nakayama, 2018.)</abbr> </a> An unusual example is shown in figure 3 to demonstrate the number of possibilities. The only logic that has to be followed for designing multigene constructs is to follow the formula <b> 5'Con(N) connects to 3'Con(N-1)</b>. In the default set up TU(N) is built with 5'Con(N) and 3'Con(N) This will result in a LVL2 plasmid harboring five transcription units. | + | The Green Expansion also offers all the parts needed for the genomic integration of one or multiple genes in cyanobacteria. This M.E.G.A. (Modularized Engineering of Genome Areas) kit convinces with a striking flexibility and a very intuitive workflow for the de novo assembly of your plasmid of choice. It encompasses five different neutral integration sites to choose from: three conventional sites frequently used in the cyanobacterial community (NSI to NSIII) as well as our own rationally designed artificial Neutral integration Site options a.N.S.o. 1 and 2 <a href="https://2019.igem.org/Team:Marburg/Design">(See: Finding new artificial Neutral integration Site options).</a>These sites show no transcriptional activity from neighboring regions according to RNA-seq data and are therefore completely orthogonal. Additionally we offer four different antibiotic markers to use (chloramphenicol, gentamicin, spectinomycin and kanamycin). With the Green Expansion up to 20 genes can be introduced into a cyanobacterial strain. |

| − | However, any other combination that follows the previously given rule will result in a functionally assembled LVL2 plasmid.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| | </html> | | </html> |

| | | | |

| | <div style="width:100%;display:flex;flex-direction:row;flex-wrap: wrap; justify-content:space-evenly; align-items:center;"> | | <div style="width:100%;display:flex;flex-direction:row;flex-wrap: wrap; justify-content:space-evenly; align-items:center;"> |

| | | | |

| − | [[File:T--Marburg--Connector_examples.png|700px|thumb|left|'''Figure 3''': <b>Unusual examples are displayed to show the range of possibilities when using the Marburg Collection </b>]] | + | [[File:GE genomic integration.png|500px|thumb|left|'''Figure 3''': Overview over the modularized editing of genome area kit (M.E.G.A. kit) ]] |

| | | | |

| | </div style> | | </div style> |

| − |

| |

| − | ===Characterization===

| |

| − |

| |

| | <html> | | <html> |

| − | <p align="justify"> | + | <br> |

| − | | + | <br> |

| − | We focused on characterizing the 5’ Connector because we expect the stronger influence on signal strengths. For characterizing our connector parts, we created 20 test plasmids with the <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560051"><i>lux</i> operon</a> as the reporter. <br>

| + | Thanks to the flexible design this expansion can also be used for the genomic modification of any chassis after the introduction of a new species specific LVL 0 integration sites to our Marburg Collection 2.0. As the workflow to build new homologies is a bit more intricate compared to the one pot on step assembly of our other parts due to the internal BsmBI cutting site, we described the workflow for that in our design section <a href="https://2019.igem.org/Team:Marburg/Design">(See: Design of neutral integration sites).</a> |

| − | In our toolbox we provide five short connectors, which solely possess the fusion sites for LVL2 cloning, and five long connectors which additionally harbor self-designed insulators. Each of these ten connectors were cloned with the constitutive promoter <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560007">K2560007 </a> (J23100), to check for effects on an active promoter, and with the Promoter Dummy to quantify the extent of transcriptional activity that reaches the Promoter Dummy. <br>

| + | <br> |

| − | | + | <br> |

| − | | + | The Green Expansion proves a valuable addition to our Marburg Collection 2.0 and to the iGEM Registry of Standard Biological Parts. It services users of our chassis and other cyanobacterial strains with a useful tool for genomic modifications but it also contributes a shell that can be used to modify any other model organism as well. |

| − | <figure> | + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | <div class="imageContainer1x2"> | + | |

| − | | + | |

| − |

| + | |

| − | <div><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/f/ff/T--Marburg--Connectoren%2BLux.png">A</div>

| + | |

| − | <div><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2018/d/d5/T--Marburg--Connectoren%2BDLux.png">B</div>

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | </div>

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | <figcaption><b>Figure 4: <br> Results of Connector measurmenet</b> <br> A) Connector constructs built with J23100 as promoter part <br> B) Connector constructs built with the Dummy Promoter as promoter part

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | </figure>

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| | </p> | | </p> |

| − |

| |

| | </html> | | </html> |

| | | | |

| − | ===Result=== | + | ===Compability=== |

| − | | + | |

| | <html> | | <html> |

| − |

| |

| | <p align="justify"> | | <p align="justify"> |

| | | | |

| − | The acquired data are shown in figure 4. The data were normalized over the test construct J23100, that was used in the promoter experiment and constructed with the connector dummies. For the five constructs with the active promoter and the long connectors we observed extremely varying signals. We measured a range from 0.2 to 2 fold change compared to the reference construct. It has been shown that the sequence directly upstream of small synthetic promoters can greatly impact the transcription efficiency <a href="https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0176013"><abbr title =" Swati B. Carr, Jacob Beal, Douglas M. Densmore , Reducing DNA context dependence in bacterial promoters (2017)" >( Carr <i>et al.</i>2017)</abbr></a>. In case of the long connectors, the sequence upstream of the promoter forms the terminator and could affect the efficiency of RNA-polymerase binding to the -35 and -10 regions. For the constructs built with small connectors, we also observed varying signals but to a lesser extent compared to the long connectors.

| + | These parts are compatible with the RCF [1000] standard and can be used in any part collection that uses the PhytoBrick standard of overhangs. For more information we recommend to head over to <a href="http://2018.igem.org/Team:Marburg/Design">Design of the Marburg Collection iGEM Marburg 2018</a>. |

| − | For all ten connectors that are provided in our toolbox, we show a tenfold range in the measured luminescence/OD600 signal. As a conclusion, we recommend to carefully consider the combination of promoter and 5’ Connector for rationally designing constructs. <br><br>

| + | |

| | | | |

| − | Taking a look at the constructs that were built with the Promoter Dummy, we also see a huge difference in the expression signals. For the long connectors we expected a negligibly low reporter expression which we observed for two out of five long 5’ Connectors resulting in a 14 fold signal reduction compared to the “Promoter Dummy” reference. The remarkably strong signal observed for the remaining three connectors could be due to inefficient terminators or cryptic promoters in the pretended “neutral sequence”. <br><br>

| + | </p> |

| | + | </html> |

| | | | |

| − | For the remaining five constructs possessing the five short 5’ connectors we observed a range from 0.3 to 5.5 fold compared to the “Promoter Dummy” reference. We are not able to give an experimental explanation for this observation but we could imagine that the LVL2 fusion sites, the only four bases that differ in these constructs, could constitute a weak promoter together with surrounding sequences.<br>

| |

| − | Summarizing the connector characterization, we found that sequences upstream of short synthetic promoters greatly affect reporter expression, which is in accordance with literature <a href="https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0176013"><abbr title =" Swati B. Carr, Jacob Beal, Douglas M. Densmore , Reducing DNA context dependence in bacterial promoters (2017)" >( Carr <i>et al.</i>2017)</abbr></a>. Moreover, we demonstrated that two of our five self-designed connectors efficiently reduce the signal resulting from other sources than the actual promoter.

| |

| − | We additionally conclude that algorithms that predict the “neutrality” of sequences alone are not sufficient to create well functioning insulators.

| |

| | | | |

| | + | ===iGEM Freiburg 2023: Testing and Documentation of BioBrick BBa_K3228069=== |

| | | | |

| − | </p> | + | To modify <i>S. elongatus</i> PCC 7942, we, iGEM Freiburg 2023, decided to use this cyanobacteria-specific shuttle vector developed by iGEM Marburg 2019 which they kindly shared with us. This shuttle vector comes with 2 origins of replication (Ori): an Ori from PCC 7942, more specifically, from one of its endogenous pANS plasmids (which makes the vector compatible with our strain), and a high copy number Ori from <i>E. coli</i>, ColE1 (for more information, visit iGEM Marburg 2019 page.) |

| − | </p> | + | |

| − | </div>

| + | |

| − | </div>

| + | |

| | | | |

| − | </article>

| + | First, we cloned the aforementioned genes for B12 production (bluB and ssuE) into the shuttle vector, creating a new plasmid, piG_CBM. Next, we attempted to modify PCC 7942 with the piG_CBM via electroporation, conjugation (tri-parental mating), and natural transformation- none of which were successful (we observed no colonies on the plates containing antibiotic resistance). The reason for conjugation not succeeding was eventually found: the shuttle vector does not encompass an OriT (basis of mobility region/bom site) which would need to be added for the conjugation. Furthermore, according to Encinas et al. 2014 [1], the conjugative plasmid used as a helper and the shuttle vector should have the same OriT to improve the efficiency of conjugation. |

| − | </html>

| + | |

| | | | |

| − | <!-- Add more about the biology of this part here

| + | The electroporation should not be affected by the lack of OriT and yet yielded no colonies after several attempts (with the exception of a faint colony for <i>S. sp.</i> PCC 6803. We did not find an explanation for why it is not working since the protocol we used from Prof Hess group, leader of the CyanoLab [2] at the University of Freiburg, was said to have a high success rate (at least for PCC 6803). |

| − | ===Usage and Biology===

| + | |

| | | | |

| − | <!-- -->

| + | Possibly, a different, PCC 7942-specific electroporation protocol could be tried to further validate the shuttle vector. Also, the natural transformation did not succeed, however, we only tried it once (due to the time limitations) and this method of transformation has a lower efficiency, as a cyanobacteria-focused research group leader Prof. Wilde, also from the University of Freiburg [3], mentioned to us. |

| − | <span class='h3bb'>Sequence and Features</span>

| + | |

| − | <partinfo>BBa_K2560011 SequenceAndFeatures</partinfo>

| + | |

| | | | |

| | + | Therefore, several repetitions and/or a different transformation protocol might be needed to validate the shuttle vector’s applicability for natural transformation. |

| | | | |

| − | <!-- Uncomment this to enable Functional Parameter display

| |

| − | ===Functional Parameters===

| |

| − | <partinfo>BBa_K2560011 parameters</partinfo>

| |

| − | <!-- -->

| |

| | | | |

| − | ===Marburg Toolbox=== | + | ====iGEM Freiburg 2023: References==== |

| − | <html>

| + | |

| − | <p align="justify">We proudly present the Marburg Collection, a novel golden-gate-based toolbox containing various parts that are compatible with the PhytoBrick system and MoClo. Compared to other bacterial toolboxes, the Marburg Collection shines with superior flexibility. We overcame the rigid paradigm of plasmid construction - thinking in fixed backbone and insert categories - by achieving complete <i> de novo </i> assembly of plasmids.

| + | |

| − | <br>

| + | |

| − | <br>

| + | |

| − | 36 connectors facilitate flexible cloning of multigene constructs and even allow for the inversion of individual transcription units. Additionally, our connectors function as insulators to avoid undesired crosstalk.

| + | |

| − | <br>

| + | |

| − | <br>

| + | |

| − | The Marburg Collection contains 123 parts in total, including:

| + | |

| − | <br>

| + | |

| − | inducible promoters, reporters, fluorescence and epitope tags, oris, resistance cassettes and genome engineering tools. To increase the value of the Marburg Collection, we additionally provide detailed experimental characterization for <i> V. natriegens </i> and a supportive software. We aspire availability of our toolbox for future iGEM teams to empower accelerated progression in their ambitious projects.</p>

| + | |

| | | | |

| − | </html>

| + | [1]Encinas D, Garcillán-Barcia MP, Santos-Merino M, Delaye L, Moya A, De La Cruz F. Plasmid Conjugation from Proteobacteria as Evidence for the Origin of Xenologous Genes in Cyanobacteria. Journal of Bacteriology [Internet]. 2014 Apr 15;196(8):1551–9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.01464-13 |

| | | | |

| | + | [2]http://www.cyanolab.de/ |

| | | | |

| − | <div style="width:100%;display:flex;flex-direction:row;flex-wrap: wrap; justify-content:space-evenly; align-items:center;">

| + | [3]https://www.bio.uni-freiburg.de/ag/wilde |

| | | | |

| − | [[File:T--Marburg--Cloning_Overview.png|800px|thumb|left|'''Figure 5''': <b> Hierarchical cloning is facilitated by subsequent Golden Gate reactions. </b> <br> Basic building blocks like promoters or terminators are stored in level 0 plasmids. Parts from each category of our collection can be chosen to built level 1 plasmids harboring a single transcription unit. Up to five transcription units can be assembled into a level 2 plasmid.]]

| + | _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| − | | + | |

| − | [[File:T--Marburg--Overview_Marburg_Toolbox.png|750px|thumb|middle|'''Figure 6''': <b> Additional bases and fusion sites ensure correct spacing and allow tags. </b> <br> Between some parts, additional base pairs were integrated to ensure correct spacing and to maintain the triplet code. We expanded our toolbox by providing N- and C- terminal tags by creating novel fusions and splitting the CDS and terminator part, respectively.]]

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | </div>

| + | |

| | | | |

| − | ===Parts of the Marburg Toolbox=== | + | ===Parts of the Green Expansion=== |

| | | | |

| | <div class="PCListIcon" style="display:flex;flex-direction:row; flex-wrap: nowrap; justify-content:space-evenly; align-items:flex-start;font-size:82%;"> | | <div class="PCListIcon" style="display:flex;flex-direction:row; flex-wrap: nowrap; justify-content:space-evenly; align-items:flex-start;font-size:82%;"> |

| | | | |

| − | [[File:T--Marburg--5'Con.png|90px|thumb|none| | + | [[File:Icon hConnector5.png|90px|thumb|none| |

| | | | |

| | <html> | | <html> |

| Line 185: |

Line 245: |

| | <b> | | <b> |

| | | | |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560011">K2560011 </a> (5'Connector Dummy) </li> | + | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228000">K3228000 </a> (aNSo1 integration up) </li> |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560055">K2560055 </a> <br>(1-6 <br> Connector) </li> | + | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228001">K3228001 </a> (aNSo2 integration up) </li> |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560065">K2560065 </a> (5'Con1) </li> | + | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228020">K3228020 </a> <br> (NS1 up) </li> |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560066">K2560066 </a> (5'Con2) </li>

| + | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228021">K3228021 </a> <br> (NS2 up) </li> |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560067">K2560067 </a> (5'Con3) </li>

| + | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228022">K3228022 </a> <br> (NS3 up) </li> |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560068">K2560068 </a> (5'Con4) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560069">K2560069 </a> (5'Con5) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560075">K2560075 </a> (5'Con1 <br> Short Res) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560076">K2560076 </a> (5'Con2 <br> Short) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560077">K2560077 </a> (5'Con3 <br> Short) </li> | + | |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560078">K2560078 </a> (5'Con4 <br> Short) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560079">K2560079 </a> (5'Con5 <br> Short) </li> | + | |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560095">K2560095 </a> (5'Con1 inv) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560096">K2560096 </a> (5'Con2 inv) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560097">K2560097 </a> (5'Con3 inv) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560098">K2560098 </a> (5'Con4 inv) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560099">K2560099 </a> (5'Con5 inv) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560105">K2560105 </a> (5'Con5 inv <br> Ori) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560107">K2560107 </a> (5'Con1 <br> Res) </li>

| + | |

| | | | |

| | </b> | | </b> |

| | </ul> | | </ul> |

| | </html>]] | | </html>]] |

| − |

| |

| − | [[File:T--Marburg--Promotor.png|90px|thumb|none|

| |

| − |

| |

| − | <html>

| |

| − | <ul>

| |

| − | <b>

| |

| − |

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560007">K2560007 </a> (J23100) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560009">K2560009 </a> (J23104) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560014">K2560014 </a> (J23106) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560015">K2560015 </a> (J23115) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560017">K2560017 </a> (J23101) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560018">K2560018 </a> (J23102) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560019">K2560019 </a> (J23103) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560020">K2560020 </a> (J23105) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560021">K2560021 </a> (J23107) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560022">K2560022 </a> (J23108) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560023">K2560023 </a> (J23109) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560024">K2560024 </a> (J23110) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560025">K2560025 </a> (J23111) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560026">K2560026 </a> (J23113) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560027">K2560027 </a> (J23114) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560028">K2560028 </a> (J23116) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560029">K2560029 </a> (J23117) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560030">K2560030 </a> (J23118) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560031">K2560031 </a> (J23119) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560123">K2560123 </a> <br>(pTet) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560124">K2560124 </a> (pTrc) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560131">K2560131 </a> (Promoter Dummy) </li>

| |

| − |

| |

| − | </ul>

| |

| − | </b>

| |

| − | </html>]]

| |

| − |

| |

| − | [[File:T--Marburg--RBS.png|90px|thumb|none|

| |

| − |

| |

| − | <html>

| |

| − | <ul>

| |

| − | <b>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560008">K2560008 </a> (B0034) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560010">K2560010 </a> (B0032) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560013">K2560013 </a> (B0031) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560016">K2560016 </a> (B0030) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560084">K2560084 </a> <br>(RBS Dummy) </li>

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | </b>

| |

| − | </ul>

| |

| − | </html>]]

| |

| − |

| |

| − | [[File:T--Marburg--CDS.png|90px|thumb|none|

| |

| − |

| |

| − | <html>

| |

| − | <ul>

| |

| − | <b>

| |

| − |

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560033">K2560033 </a> (E1010) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560041">K2560041 </a> (E0030) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560042">K2560042 </a> (sfGFP) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560043">K2560043 </a> (sfGFP Vn) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560047">K2560047 </a> (Cas9) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560051">K2560051 </a> <br>(Lux Operon) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560054">K2560054 </a> (dCas9) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560082">K2560082 </a> <br>(CDS Dummy) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560114">K2560114 </a> (LacZ Alpha) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560128">K2560128 </a> (K660004) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560135">K2560135 </a> <br>(SXT Beta) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560268">K2560268 </a> <br>(tfox Vc) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560269">K2560269 </a> <br>(tfox Vn) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560270">K2560270 </a> <br>(SXT) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560271">K2560272 </a> <br>(flp recombinase) </li>

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | </ul>

| |

| − | </b>

| |

| − | </html>]]

| |

| − |

| |

| | | | |

| | [[File:T--Marburg--Terminator.png|90px|thumb|none| | | [[File:T--Marburg--Terminator.png|90px|thumb|none| |

| Line 291: |

Line 260: |

| | <ul> | | <ul> |

| | <b> | | <b> |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560034">K2560034 </a> (B0010) </li> | + | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228004">K3228004 </a> (shortTB0010) </li> |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560035">K2560035 </a> (B0015) </li> | + | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228005">K3228005 </a> (shortTB0015) </li> |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560081">K2560081 </a> (Terminator Dummy) </li> | + | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228006">K3228006 </a> (shortTB1002) </li> |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560089">K2560089 </a> (B1002) </li> | + | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228007">K3228007 </a> (shortTB1003) </li> |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560091">K2560091 </a> (B1003) </li> | + | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228008">K3228008 </a> (shortTB1004) </li> |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560093">K2560093 </a> (B1006) </li> | + | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228009">K3228009 </a> (shortTB1005) </li> |

| − | | + | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228010">K3228010 </a> (shortTB1006) </li> |

| | + | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228011">K3228011 </a> (shortTB1007) </li> |

| | + | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228012">K3228012 </a> (shortTB1008) </li> |

| | + | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228013">K3228013 </a> (shortTB1009) </li> |

| | + | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228014">K3228014 </a> (shortTB1010) </li> |

| | + | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228015">K3228015 </a> (shortDummy) </li> |

| | | | |

| | </b> | | </b> |

| Line 303: |

Line 277: |

| | </html>]] | | </html>]] |

| | | | |

| − |

| |

| − | [[File:T--Marburg--3'Con.png|90px|thumb|none|<html>

| |

| − | <ul> <b>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560012">K2560012 </a> (3'Connector Dummy) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560070">K2560070 </a> (3'Con1) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560071">K2560071 </a> (3'Con2) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560072">K2560072 </a> (3'Con3) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560073">K2560073 </a> (3'Con4) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560080">K2560080 </a> (3'Con5 Ori) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560100">K2560100 </a> (3'Con1 inv <br>Short) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560101">K2560101 </a> (3'Con2 inv <br>Short) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560102">K2560102 </a> (3'Con3 inv <br>Short) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560103">K2560103 </a> (3'Con4 inv <br>Short) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560104">K2560104 </a> (3'Con5 inv <br>Short) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560106">K2560106 </a> (3'Con1 inv <br>Short Res) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560108">K2560108 </a> (3'Con1 inv) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560109">K2560109 </a> (3'Con1 inv <br>Res) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560110">K2560110 </a> (3'Con2 inv) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560111">K2560111 </a> (3'Con3 inv) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560112">K2560112 </a> (3'Con4 inv) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560113">K2560113 </a> (3'Con5 inv) </li>

| |

| − |

| |

| − | </ul>

| |

| − | </b>

| |

| − | </html>]]

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | [[File:T--Marburg--ORI.png|90px|thumb|none|<html>

| |

| − | <ul> <b>

| |

| − |

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560036">K2560036 </a> (ColE1) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560037">K2560037 </a> (pMB1) </li>

| |

| − | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560046">K2560046 </a> (p15A) </li>

| |

| − |

| |

| − | </ul>

| |

| − | </b>

| |

| − | </html>]]

| |

| − |

| |

| | [[File:T--Marburg--Antibiotic_Resistance.png|90px|thumb|none| | | [[File:T--Marburg--Antibiotic_Resistance.png|90px|thumb|none| |

| | <html> | | <html> |

| Line 347: |

Line 283: |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560048">K2560048 </a> (Cam. Res. RFP) </li> | + | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228016">K3228016 </a> (SpecRes_short) </li> |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560056">K2560056 </a> <br> (Kan. Res. (pSB3K3) RFP) </li> | + | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228017">K3228017 </a> <br> (CmlRes_short) </li> |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560057">K2560057 </a> <br> (Kan. Res. (pSB3K3) GFP) </li> | + | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228018">K3228018 </a> <br> (TetRes_short) </li> |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560058">K2560058 </a> <br> (Tet. Res. (pSB3T5) RFP) </li> | + | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228019">K3228019 </a> <br> (KanRes_short) </li> |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560059">K2560059 </a> <br> (Tet. Res. (pSB3T5) GFP) </li> | + | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228027">K3228027 </a> <br> (GenRes_short) </li> |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560125">K2560125 </a> (Carb. Res. RFP) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560126">K2560126 </a> (Carb. Res. GFP) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560127">K2560127 </a> (Carb. Res. into BBa_K2560002) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560132">K2560132 </a> (Cam. Res. into BBa_K2560002) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560133">K2560133 </a> <br> (Kan. Res. into BBa_K2560002) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560134">K2560134 </a> <br> (Tet. Res. into BBa_K2560002) </li>

| + | |

| | | | |

| | </ul> | | </ul> |

| | </b> | | </b> |

| | </html>]] | | </html>]] |

| − | </div>

| |

| | | | |

| − | ===Tags and Entry Vectors===

| + | [[File:Icon hConnector3.png|90px|thumb|none|<html> |

| − | <div class="PCListIcon" style="display:flex;flex-direction:row; flex-wrap: nowrap; align-items:flex-start; font-size:82%;"> | + | <ul> <b> |

| | | | |

| | + | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228002">K3228002 </a> (aNSo1 integration down) </li> |

| | + | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228003">K3228003 </a> (aNSo1 integration down) </li> |

| | + | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228023">K3228023 </a> <br> (NS1 down) </li> |

| | + | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228024">K3228024 </a> <br> (NS2 down) </li> |

| | + | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228025">K3228025 </a> <br> (NS3 down) </li> |

| | | | |

| − | [[File:T--Marburg--N-Tag.png|90px|thumb|middle|

| + | </ul> |

| − | <html>

| + | |

| − | <ul>

| + | |

| − | <b>

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560060">K2560060 </a> (E1010 4x) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560063">K2560063 </a> (sfGFP 4x) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560085">K2560085 </a> <br> (His-Tag 4x) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560087">K2560087 </a> (FLAG-Tag 4x) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560129">K2560129 </a> (K660004 4x) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560257">K2560257 </a> (Streptag 4x) </li>

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | </ul> | + | |

| | </b> | | </b> |

| | </html>]] | | </html>]] |

| | | | |

| | + | [[File:Icon Shuttlevector.png|90px|thumb|none|<html> |

| | + | <ul> <b> |

| | | | |

| − | [[File:T--Marburg--C-Tag.png|90px|thumb|middle|

| + | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228026">K3228026 </a> (oriT integration) </li> |

| − | <html> | + | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228069">K3228069 </a> (panS SpecRes LVL1) </li> |

| − | <ul> | + | <li> <a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3228089">K3228089 </a> (panS KanRes LVL2) </li> |

| − | <b> | + | |

| | | | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560061">K2560061 </a> (E1010 5a) </li>

| + | </ul> |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560062">K2560062 </a> (B0015 5b) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560064">K2560064 </a> (sfGFP 5a) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560086">K2560086 </a> <br> (His-Tag 5a) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560088">K2560088 </a> (FLAG-Tag 5a) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560090">K2560090 </a> (B1002 5b) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560092">K2560092 </a> (B1003 5b) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560094">K2560094 </a> (B1006 5b) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560117">K2560117 </a> (I11012 5a) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560118">K2560118 </a> (M0050 5a) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560119">K2560119 </a> (M0051 5a) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560130">K2560130 </a> (K660004 5a) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560258">K2560258 </a> (Streptag 5a) </li>

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | </ul> | + | |

| | </b> | | </b> |

| | </html>]] | | </html>]] |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | [[File:T--Marburg--Entry_Vector.png|90px|thumb|middle|

| + | </div> |

| − | <html>

| + | |

| − | <ul>

| + | |

| − | <b>

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560001">K2560001 </a> (Entry Vector with RFP dropout) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560002">K2560002 </a> (Entry Vector with GFP dropout) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560005">K2560005 </a> (Resistance Entry Vector with RFP Dropout) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560006">K2560006 </a> (Resistance Entry Vector with GFP Dropout) </li>

| + | |

| − | <li><a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2560305">K2560305 </a> (gRNA Entry Vector with GFP Dropout) </li>

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | </ul>

| + | |

| − | </b>

| + | |

| − | </html>]] | + | |