Difference between revisions of "Part:BBa K3868102"

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

:'''Fig 1. The Schematic diagram of pET-AMP-eGFP ''' | :'''Fig 1. The Schematic diagram of pET-AMP-eGFP ''' | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | =Improve From NNU-China 2021= | ||

| + | '''Group''':[https://2021.igem.org/Team:NNU-China iGEM Team NNU-China 2021] | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Author''': Yan Xu | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Background== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Herein, to improve the production of AMPs, the RBS library of T7 RNA polymerase based on Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) was constructed, and then the most suitable expression host could be screened by high throughput screening. Besides, promoter engineering is also an effective strategy to improve the expression of genes. Promoter plays a significant role in gene transcription because it controls the binding of RNA polymerase to DNA. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Therefore, we are trying to use promoter engineering to improve BioBrick <partinfo>BBa_K3578010 </partinfo> from the 2020 iGEM worldshaper-Nanjing Team, and improve the ability of Yarrowia lipolytica to utilize the starch as an improvement. | ||

| + | |||

| + | We hypothesized that the expression level of glucoamylase could be increased through using the more potent promoters. For this, we scanned the genome of Y. lipolytica and characterized 20 endogenous promoters in Y. lipolytica. | ||

| + | ==Design== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Given Y. lipolytica's metabolism with a high propensity for flux to tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediates, the promoters chosen are primarily centering around the carbon metabolism and tricarboxylic acid cycle. We selected 20 endogenous promoters (Table1) in Y. lipolytica for genetic parts characterization. Specifically, these genes include YALI0E00638g(<partinfo>BBa_K3868074 </partinfo> ), YALI0F07711p(<partinfo>BBa_K3868075 </partinfo> ), YALI0A15972p(<partinfo>BBa_K3868076 </partinfo> ), YALI0E26004p(<partinfo>BBa_K3868077 </partinfo> ), YALI0D02277p(<partinfo>BBa_K3868078 </partinfo> ), YALI0F16819p(<partinfo>BBa_K3868079 </partinfo> ), YALI0D06325p(<partinfo>BBa_K3868080 </partinfo> ), YALI0D23683p(<partinfo>BBa_K3868081 </partinfo> ), YALI0F02607p(<partinfo>BBa_K3868082 </partinfo> ), YALI0D06215p(<partinfo>BBa_K3868083 </partinfo> ), YALI0C19965p(<partinfo>BBa_K3868084 </partinfo> ), YALI0E02090p(<partinfo>BBa_K3868085 </partinfo> ), YALI0D06930p(<partinfo>BBa_K3868086 </partinfo> ), YALI0A15147p(<partinfo>BBa_K3868087 </partinfo> ), YALI0A16379g(<partinfo>BBa_K3868088 </partinfo> ), YALI0F0960p(<partinfo>BBa_K3868089 </partinfo> ), tYALI0C19624p(<partinfo>BBa_K3868090 </partinfo> ), YALI0B10406p(<partinfo>BBa_K3868091 </partinfo> ), YALI0E18590p(<partinfo>BBa_K3868092 </partinfo> ), and YALI0D17864p(<partinfo>BBa_K3868093 </partinfo> ). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Next, to test the strength of these promoters, we amplified the 1500 bp promoter and 5′ UTR (5′-untranslated region) sequences of the target genes, and further constructed 20 recombinant plasmids by Gibson Assembly method. Recombinant plasmids were constructed based on the original plasmid pYLXP'-PTEF-Nluc harboring with the nanoluc luciferase gene (Nluc) as the reporter by Gibson Assembly method. For example, the recombinant plasmid of pYLXP’-P1-Nluc was constructed using linearized pYLXP'-PTEF-Nluc (digested by AvrII and NheI) and the PCR-amplified promoter P1 sequences by Gibson Assembly. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Then, 20 recombinant plasmids were transformed into Y. lipolytica po1fk. In brief, one milliliter cells were harvested during the exponential growth phase (16-24 h) from 2 mL YPD medium (yeast extract 10 g/L, peptone 20 g/L, and glucose 20 g/L) in the 14-mL shake tube, and washed twice with 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Then, cells were resuspended in 105 µL transformation solution, containing 90 µL 50% PEG4000, 5 µL lithium acetate (2M), 5 µL boiled single stand DNA (salmon sperm, denatured) and 5 µL DNA products (including 200-500 ng of plasmids, lined plasmids or DNA fragments), and incubated at 39 ℃ for 1 h, then spread on selected plates. The transformants were selected by using the leucine-defective solid medium. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Subsequently, shaking flasks were performed to characterize the strength of promoters by the Nluc analysis, which has been reported in the previous study (Liu et al., 2019). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Furthermore, the identified more potent promoter was used to express glucoamylase. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <div align="center"> | ||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src="https://2021.igem.org/wiki/images/2/2e/T--NNU-China--part-improving-2.png" width="100%" style="float:center"> | ||

| + | <figcaption> | ||

| + | <p style="font-size:1rem"> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | </figcaption> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | <div align="center"> | ||

| + | :'''Table 1: The genetic information of the selected 20 endogenous promoters''' | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | ==Result== | ||

| + | |||

| + | After amplifying the 1500 bp promoter and 5′ UTR (5′-untranslated region) sequences of the target genes, we assembled these sequences with linearized pYLXP'-PTEF-Nluc (digested by AvrII and NheI) to construct the recombinant plasmids (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2), including pYLXP’-P1-Nluc(<partinfo>BBa_K3868110 </partinfo> ), pYLXP’-P2-Nluc(<partinfo>BBa_K3868111 </partinfo> ), pYLXP’-P3-Nluc(<partinfo>BBa_K3868112 </partinfo> ), pYLXP’-P4-Nluc(<partinfo>BBa_K3868113 </partinfo> ), pYLXP’-P5-Nluc(<partinfo>BBa_K3868114 </partinfo> ), pYLXP’-P6-Nluc(<partinfo>BBa_K3868115 </partinfo> ), pYLXP’-P7-Nluc(<partinfo>BBa_K3868116 </partinfo> ), pYLXP’-P8-Nluc(<partinfo>BBa_K3868117 </partinfo> ), pYLXP’-P9-Nluc(<partinfo>BBa_K3868118 </partinfo> ), pYLXP’-P10-Nluc(<partinfo>BBa_K3868119 </partinfo> ), pYLXP’-P11-Nluc(<partinfo>BBa_K3868120 </partinfo> ), pYLXP’-P12-Nluc(<partinfo>BBa_K3868121 </partinfo> ), pYLXP’-P13-Nluc(<partinfo>BBa_K3868122 </partinfo> ), pYLXP’-P14-Nluc(<partinfo>BBa_K3868123 </partinfo> ), pYLXP’-P15-Nluc(<partinfo>BBa_K3868124 </partinfo> ), pYLXP’-P16-Nluc(<partinfo>BBa_K3868125 </partinfo> ), pYLXP’-P17-Nluc(<partinfo>BBa_K3868126 </partinfo> ), pYLXP’-P18-Nluc(<partinfo>BBa_K3868127 </partinfo> ), pYLXP’-P19-Nluc(<partinfo>BBa_K3868128 </partinfo> ), and pYLXP’-P20-Nluc(<partinfo>BBa_K3868129 </partinfo> ). | ||

| + | |||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <div align="center"> | ||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src="https://2021.igem.org/wiki/images/9/96/T--NNU-China--part-improving-1.png" width="100%" style="float:center"> | ||

| + | <figcaption> | ||

| + | <p style="font-size:1rem"> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | </figcaption> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | <div align="center"> | ||

| + | :'''Fig. 1 The maps of recombinant plasmids for characterizing the strength of promoters''' | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | These recombinant plasmids were further transformed into Y. lipolytica po1f (Fig. 2), and obtained strains po1f-P1-Nluc, po1f-P2-Nluc, po1f-P3-Nluc, po1f-P4-Nluc, po1f-P5-Nluc, po1f-P6-Nluc, po1f-P7-Nluc, po1f-P8-Nluc, po1f-P9-Nluc, po1f-P10-Nluc, po1f-P11-Nluc, po1f-P12-Nluc, po1f-P13-Nluc, po1f-P14-Nluc, po1f-P15-Nluc, po1f-P16-Nluc, po1f-P17-Nluc, po1f-P18-Nluc, po1f-P19-Nluc, and po1f-P20-Nluc. Next, we performed the shaking flask of these engineering strains and tested the Nluc analysis. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <div align="center"> | ||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src="https://2021.igem.org/wiki/images/b/b8/T--NNU-China--part-improving-6.png" width="80%" style="float:center"> | ||

| + | <figcaption> | ||

| + | <p style="font-size:1rem"> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | </figcaption> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | <div align="center"> | ||

| + | :'''Fig. 2 A. The processes of constructing plasmids. B. Characterizing the strength of promoters ''' | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The results of the Nluc analysis showed that strains po1f-P2-Nluc and po1f-P17-Nluc generated the highest Nluc activities compared with other strains (Fig. 3), indicating promoter P2 and P17 are two strong promoters. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <div align="center"> | ||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src="https://2021.igem.org/wiki/images/7/7c/T--NNU-China--part-improving-4-1.png" width="100%" style="float:center"> | ||

| + | <figcaption> | ||

| + | <p style="font-size:1rem"> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | </figcaption> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | <div align="center"> | ||

| + | :'''Fig. 3 Nanoluc luciferase gene was used as a reporter gene to quantify the promoter strength.''' | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | Then, we replaced the promoter of plasmid pUC-Pexp-AnGlu(<partinfo>BBa_K3578010 </partinfo>)with identified promoters P2 and P17, and obtained the recombinant plasmids pUC-P2-AnGlu and pUC-P17-AnGlu (Fig. 4), respectively. Further, we transformed plasmids pUC-P2-AnGlu and pUC-P17-AnGlu into po1f, and obtained strains po1f-P2-AnGlu and po1f-P17-AnGlu. Subsequently, we performed the shaking flask with using starch as the sole carbon source. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <div align="center"> | ||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src="https://2021.igem.org/wiki/images/e/ef/T--NNU-China--part-improving-5-1.png" width="80%" style="float:center"> | ||

| + | <figcaption> | ||

| + | <p style="font-size:1rem"> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | </figcaption> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | <div align="center"> | ||

| + | :'''Fig. 4 The maps of recombinant plasmids of pUC-P2-AnGlu and pUC-P17-AnGlu''' | ||

| + | </div> | ||

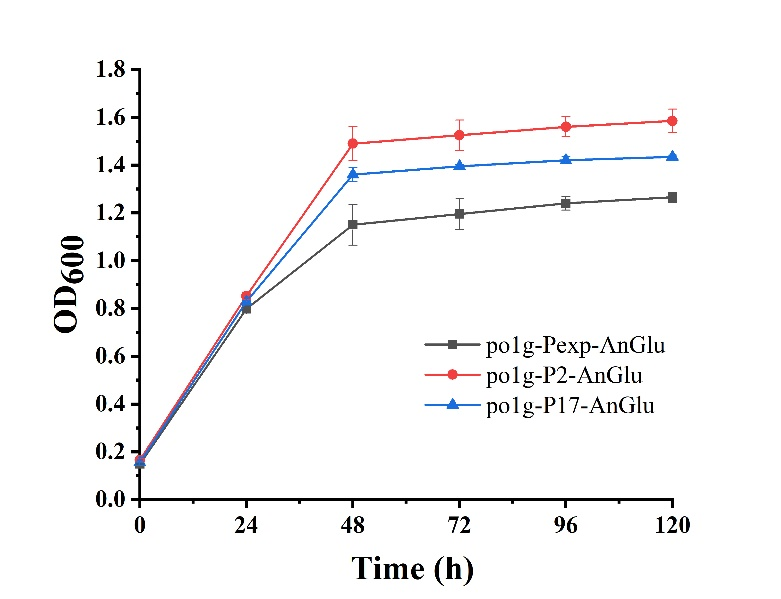

| + | As shown in Fig. 5, we can see that po1f-P2-AnGlu and po1f-P17-AnGlu both showed better cell growth than that of the control strain po1f-Pexp-AnGlu (<partinfo>BBa_K3578010 </partinfo>), indicating that glycolase has been overexpressed by promoters P2 and P17. Moreover, among these strains, the cell growth of po1f-P2-AnGlu was the highest. That is to say that the use of strong promoter expression can improve glycolase activity, indicating that our strategy is indeed effective. | ||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <div align="center"> | ||

| + | <figure> | ||

| + | <img src="https://2021.igem.org/wiki/images/archive/b/b4/20211014114941%21T--NNU-China--part-improving-5-2.png" width="50%" style="float:center"> | ||

| + | <figcaption> | ||

| + | <p style="font-size:1rem"> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | </figcaption> | ||

| + | </figure> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | <div align="center"> | ||

| + | :'''Fig. 5 The maps of recombinant plasmids of pUC-P2-AnGlu and pUC-P17-AnGlu''' | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | Rennig, M., Martinez, V., Mirzadeh, K., Dunas, F., Rojsater, B., Daley, D. O., & Nørholm, M. H. (2018). TARSyn: tunable antibiotic resistance devices enabling bacterial synthetic evolution and protein production. ACS Synthetic Biology, 7(2), 432-442. | ||

| + | |||

<!-- Uncomment this to enable Functional Parameter display | <!-- Uncomment this to enable Functional Parameter display | ||

===Functional Parameters=== | ===Functional Parameters=== | ||

<partinfo>BBa_K3868102 parameters</partinfo> | <partinfo>BBa_K3868102 parameters</partinfo> | ||

<!-- --> | <!-- --> | ||

Revision as of 01:48, 14 October 2022

pET-Alloferon-1-eGFP

pET--Alloferon-1-eGFP plasmid contains pT7, lacO,Alloferon-1, thrombin, eGFP-His-tag etc.Based on the plasmid of pET-24a, the C-terminal of Alloferon-1 was fused with eGFP in order to characterize the yield of Alloferon-1. Moreover, in order to purify the Alloferon-1, the enzyme loci of thrombin was inserted between Alloferon-1 and eGFP, and the label of 6*His was inserted at the end of eGFP, yielding the plasmid of pET-Alloferon-1-eGFP. The fluorescence intensity of eGFP could be used to indicate the expression level of Alloferon-1.

Sequence and Features

- 10COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[10]

- 12COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[12]

- 21COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[21]

- 23COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[23]

- 25COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[25]

- 1000COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[1000]

Usage and Biology

Based on the plasmid of pET-24a. The C-terminal of Antibacterial peptides(AMP) was fused with eGFP in order to characterize the yield of AMP. The pET-24a was provided by our PI. Moreover, in order to purify the AMP, the enzyme loci of thrombin was inserted between AMP and eGFP, and the label of 6*His was inserted at the end of eGFP, yielding the plasmid of pET-AMP-eGFP. As a result, the pET-AMP-eGFP plasmids could not only indicate the expression level of AMPs by the fluorescence intensity of eGFP, but also be good for later purification and separation with His-Tag and the enzyme loci of thrombin. (Fig. 1)

- Fig 1. The Schematic diagram of pET-AMP-eGFP

Improve From NNU-China 2021

Group:iGEM Team NNU-China 2021

Author: Yan Xu

Background

Herein, to improve the production of AMPs, the RBS library of T7 RNA polymerase based on Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) was constructed, and then the most suitable expression host could be screened by high throughput screening. Besides, promoter engineering is also an effective strategy to improve the expression of genes. Promoter plays a significant role in gene transcription because it controls the binding of RNA polymerase to DNA.

Therefore, we are trying to use promoter engineering to improve BioBrick BBa_K3578010 from the 2020 iGEM worldshaper-Nanjing Team, and improve the ability of Yarrowia lipolytica to utilize the starch as an improvement.

We hypothesized that the expression level of glucoamylase could be increased through using the more potent promoters. For this, we scanned the genome of Y. lipolytica and characterized 20 endogenous promoters in Y. lipolytica.

Design

Given Y. lipolytica's metabolism with a high propensity for flux to tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediates, the promoters chosen are primarily centering around the carbon metabolism and tricarboxylic acid cycle. We selected 20 endogenous promoters (Table1) in Y. lipolytica for genetic parts characterization. Specifically, these genes include YALI0E00638g(BBa_K3868074 ), YALI0F07711p(BBa_K3868075 ), YALI0A15972p(BBa_K3868076 ), YALI0E26004p(BBa_K3868077 ), YALI0D02277p(BBa_K3868078 ), YALI0F16819p(BBa_K3868079 ), YALI0D06325p(BBa_K3868080 ), YALI0D23683p(BBa_K3868081 ), YALI0F02607p(BBa_K3868082 ), YALI0D06215p(BBa_K3868083 ), YALI0C19965p(BBa_K3868084 ), YALI0E02090p(BBa_K3868085 ), YALI0D06930p(BBa_K3868086 ), YALI0A15147p(BBa_K3868087 ), YALI0A16379g(BBa_K3868088 ), YALI0F0960p(BBa_K3868089 ), tYALI0C19624p(BBa_K3868090 ), YALI0B10406p(BBa_K3868091 ), YALI0E18590p(BBa_K3868092 ), and YALI0D17864p(BBa_K3868093 ).

Next, to test the strength of these promoters, we amplified the 1500 bp promoter and 5′ UTR (5′-untranslated region) sequences of the target genes, and further constructed 20 recombinant plasmids by Gibson Assembly method. Recombinant plasmids were constructed based on the original plasmid pYLXP'-PTEF-Nluc harboring with the nanoluc luciferase gene (Nluc) as the reporter by Gibson Assembly method. For example, the recombinant plasmid of pYLXP’-P1-Nluc was constructed using linearized pYLXP'-PTEF-Nluc (digested by AvrII and NheI) and the PCR-amplified promoter P1 sequences by Gibson Assembly.

Then, 20 recombinant plasmids were transformed into Y. lipolytica po1fk. In brief, one milliliter cells were harvested during the exponential growth phase (16-24 h) from 2 mL YPD medium (yeast extract 10 g/L, peptone 20 g/L, and glucose 20 g/L) in the 14-mL shake tube, and washed twice with 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Then, cells were resuspended in 105 µL transformation solution, containing 90 µL 50% PEG4000, 5 µL lithium acetate (2M), 5 µL boiled single stand DNA (salmon sperm, denatured) and 5 µL DNA products (including 200-500 ng of plasmids, lined plasmids or DNA fragments), and incubated at 39 ℃ for 1 h, then spread on selected plates. The transformants were selected by using the leucine-defective solid medium.

Subsequently, shaking flasks were performed to characterize the strength of promoters by the Nluc analysis, which has been reported in the previous study (Liu et al., 2019).

Furthermore, the identified more potent promoter was used to express glucoamylase.

- Table 1: The genetic information of the selected 20 endogenous promoters

Result

After amplifying the 1500 bp promoter and 5′ UTR (5′-untranslated region) sequences of the target genes, we assembled these sequences with linearized pYLXP'-PTEF-Nluc (digested by AvrII and NheI) to construct the recombinant plasmids (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2), including pYLXP’-P1-Nluc(BBa_K3868110 ), pYLXP’-P2-Nluc(BBa_K3868111 ), pYLXP’-P3-Nluc(BBa_K3868112 ), pYLXP’-P4-Nluc(BBa_K3868113 ), pYLXP’-P5-Nluc(BBa_K3868114 ), pYLXP’-P6-Nluc(BBa_K3868115 ), pYLXP’-P7-Nluc(BBa_K3868116 ), pYLXP’-P8-Nluc(BBa_K3868117 ), pYLXP’-P9-Nluc(BBa_K3868118 ), pYLXP’-P10-Nluc(BBa_K3868119 ), pYLXP’-P11-Nluc(BBa_K3868120 ), pYLXP’-P12-Nluc(BBa_K3868121 ), pYLXP’-P13-Nluc(BBa_K3868122 ), pYLXP’-P14-Nluc(BBa_K3868123 ), pYLXP’-P15-Nluc(BBa_K3868124 ), pYLXP’-P16-Nluc(BBa_K3868125 ), pYLXP’-P17-Nluc(BBa_K3868126 ), pYLXP’-P18-Nluc(BBa_K3868127 ), pYLXP’-P19-Nluc(BBa_K3868128 ), and pYLXP’-P20-Nluc(BBa_K3868129 ).

- Fig. 1 The maps of recombinant plasmids for characterizing the strength of promoters

These recombinant plasmids were further transformed into Y. lipolytica po1f (Fig. 2), and obtained strains po1f-P1-Nluc, po1f-P2-Nluc, po1f-P3-Nluc, po1f-P4-Nluc, po1f-P5-Nluc, po1f-P6-Nluc, po1f-P7-Nluc, po1f-P8-Nluc, po1f-P9-Nluc, po1f-P10-Nluc, po1f-P11-Nluc, po1f-P12-Nluc, po1f-P13-Nluc, po1f-P14-Nluc, po1f-P15-Nluc, po1f-P16-Nluc, po1f-P17-Nluc, po1f-P18-Nluc, po1f-P19-Nluc, and po1f-P20-Nluc. Next, we performed the shaking flask of these engineering strains and tested the Nluc analysis.

- Fig. 2 A. The processes of constructing plasmids. B. Characterizing the strength of promoters

The results of the Nluc analysis showed that strains po1f-P2-Nluc and po1f-P17-Nluc generated the highest Nluc activities compared with other strains (Fig. 3), indicating promoter P2 and P17 are two strong promoters.

- Fig. 3 Nanoluc luciferase gene was used as a reporter gene to quantify the promoter strength.

Then, we replaced the promoter of plasmid pUC-Pexp-AnGlu(BBa_K3578010)with identified promoters P2 and P17, and obtained the recombinant plasmids pUC-P2-AnGlu and pUC-P17-AnGlu (Fig. 4), respectively. Further, we transformed plasmids pUC-P2-AnGlu and pUC-P17-AnGlu into po1f, and obtained strains po1f-P2-AnGlu and po1f-P17-AnGlu. Subsequently, we performed the shaking flask with using starch as the sole carbon source.

- Fig. 4 The maps of recombinant plasmids of pUC-P2-AnGlu and pUC-P17-AnGlu

As shown in Fig. 5, we can see that po1f-P2-AnGlu and po1f-P17-AnGlu both showed better cell growth than that of the control strain po1f-Pexp-AnGlu (BBa_K3578010), indicating that glycolase has been overexpressed by promoters P2 and P17. Moreover, among these strains, the cell growth of po1f-P2-AnGlu was the highest. That is to say that the use of strong promoter expression can improve glycolase activity, indicating that our strategy is indeed effective.

- Fig. 5 The maps of recombinant plasmids of pUC-P2-AnGlu and pUC-P17-AnGlu

References

Rennig, M., Martinez, V., Mirzadeh, K., Dunas, F., Rojsater, B., Daley, D. O., & Nørholm, M. H. (2018). TARSyn: tunable antibiotic resistance devices enabling bacterial synthetic evolution and protein production. ACS Synthetic Biology, 7(2), 432-442.