Difference between revisions of "Part:BBa K1321340"

| (12 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

Double cellulose binding domain (dCBD) using two cellulose binding domains from ''Trichoderma reesei'' cellobiohydrolases, with an N-terminal linker and internal linker sequence between the two domains which is derived from the endogenous cellobiohydrolase linker sequence. | Double cellulose binding domain (dCBD) using two cellulose binding domains from ''Trichoderma reesei'' cellobiohydrolases, with an N-terminal linker and internal linker sequence between the two domains which is derived from the endogenous cellobiohydrolase linker sequence. | ||

| + | Please see below for AutoAnnotator information about the final protein product. | ||

===Usage and Biology=== | ===Usage and Biology=== | ||

| Line 9: | Line 10: | ||

This part is based on the double cellulose-binding domain construct (CBDcbh2-linker-CBDcbh1) synthesised and characterised by Linder ''et al'' [http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.271.35.21268 (1)] who found that this double CBD had higher affinity for cellulose than either of the two CBDs on their own. The main difference is that our part contains an additional linker sequence on the N-terminus of the protein. | This part is based on the double cellulose-binding domain construct (CBDcbh2-linker-CBDcbh1) synthesised and characterised by Linder ''et al'' [http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.271.35.21268 (1)] who found that this double CBD had higher affinity for cellulose than either of the two CBDs on their own. The main difference is that our part contains an additional linker sequence on the N-terminus of the protein. | ||

| − | + | The two CBDs are from the fungus ''T. reesei'' (Hypocrea jecorina) Exocellobiohydrolase (Exoglucanase) I (cbh1), uniprot ID [http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P62694 P62694]; and Exocellobiohydrolase (Exoglucanase) II, uniprot ID [http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P07987 P07987] (cbh2); with a linker peptide between the two CBDs and at the N-terminus of the protein. Both linkers are the same amino acid sequence and are based on the endogenous linker sequences that exists in cbh1 and cbh2 genes. The linker sequence is PGANPPGTTTTSRPATTTGSSPGP which is the same as used by Linder ''et al'' [http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.271.35.21268 (1)]. The first three amino acids are from the cbh2 endogenous linker, and the rest is from the cbh1 endogenous linker. CBDcbh1 is placed C-terminal to CBDcbh2 because naturally CBDcbh1 is a C-terminal domain and CBDcbh2 is an N-terminal domain. Both CBDs are from the [http://www.cazy.org/CBM1.html CBM family 1]. The precise location of the CBD within the cbh genes was slightly different according to the uniprot annotations and the sequence used by Linder ''et al'' [http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.271.35.21268 (1)]; we chose to use the sequence from the paper since the protein was expressed and characterised successfully. | |

| + | |||

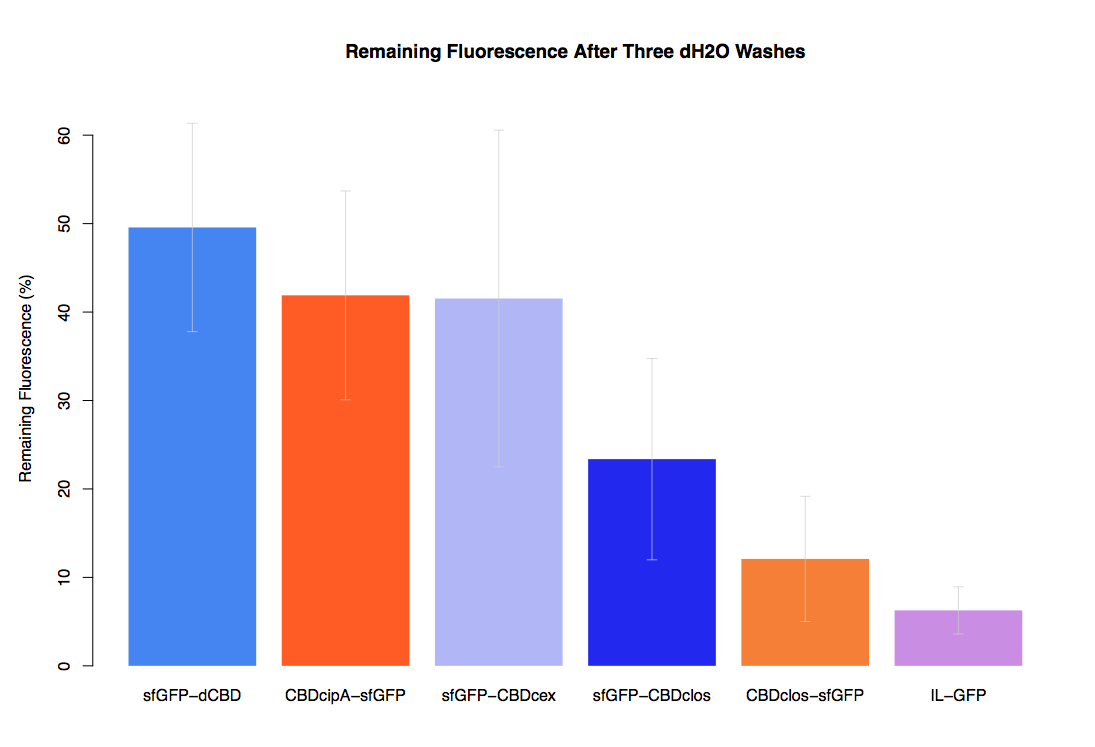

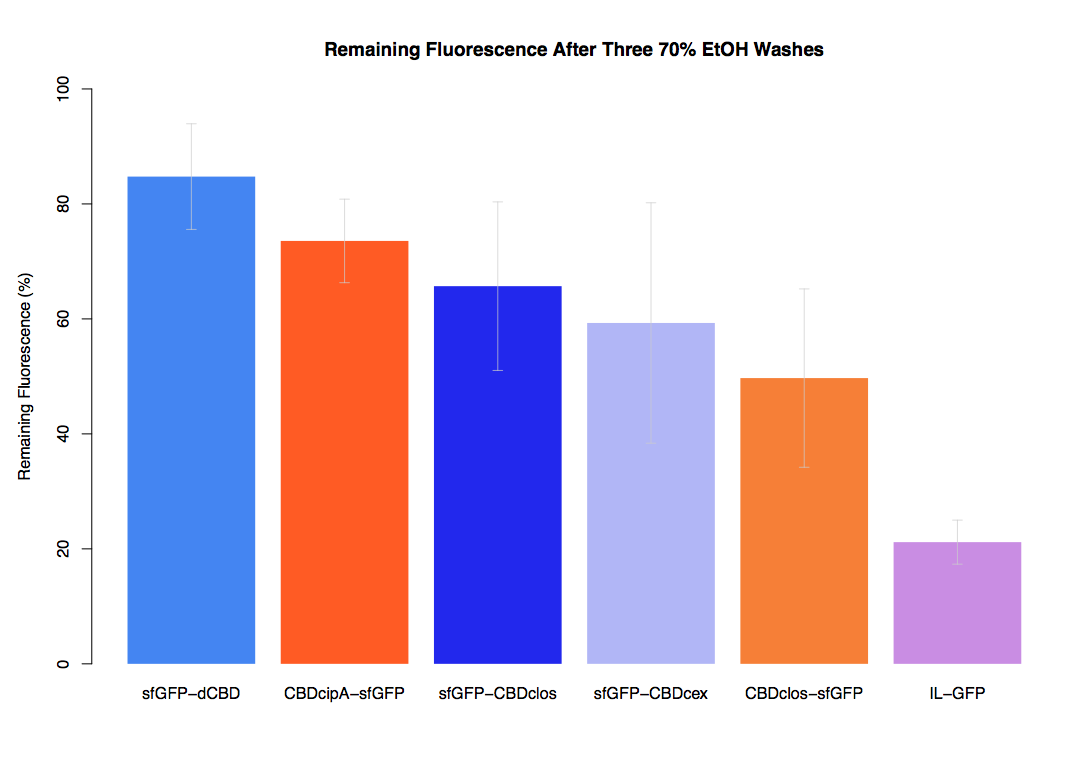

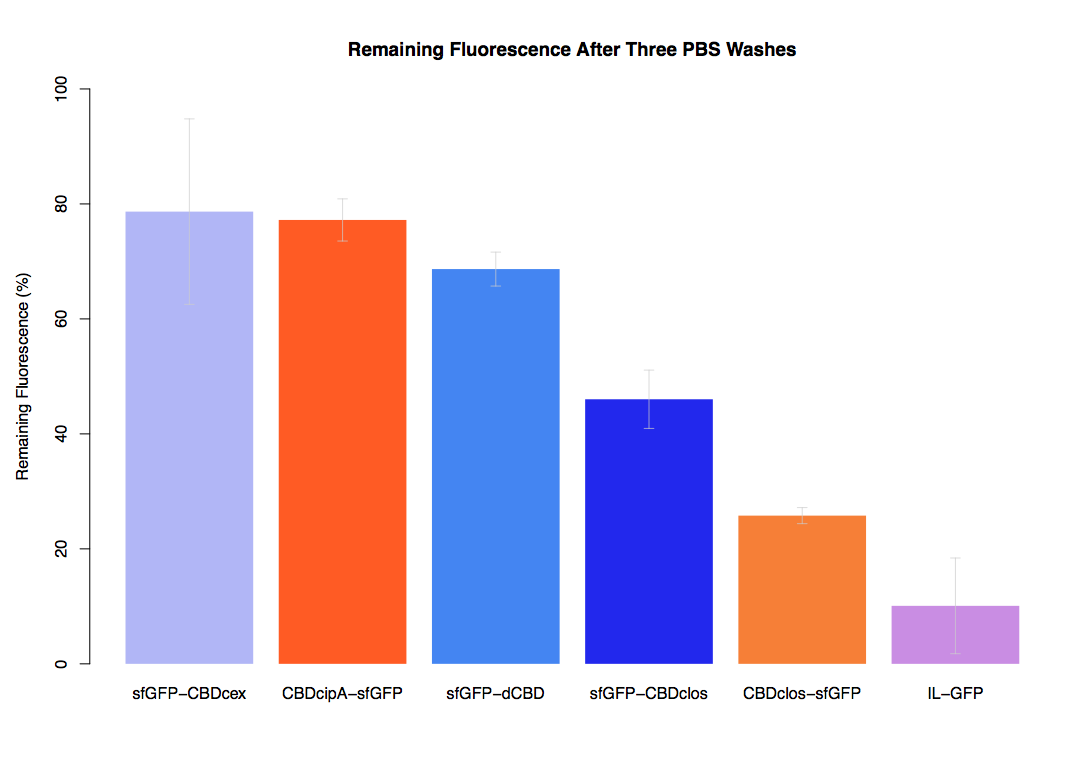

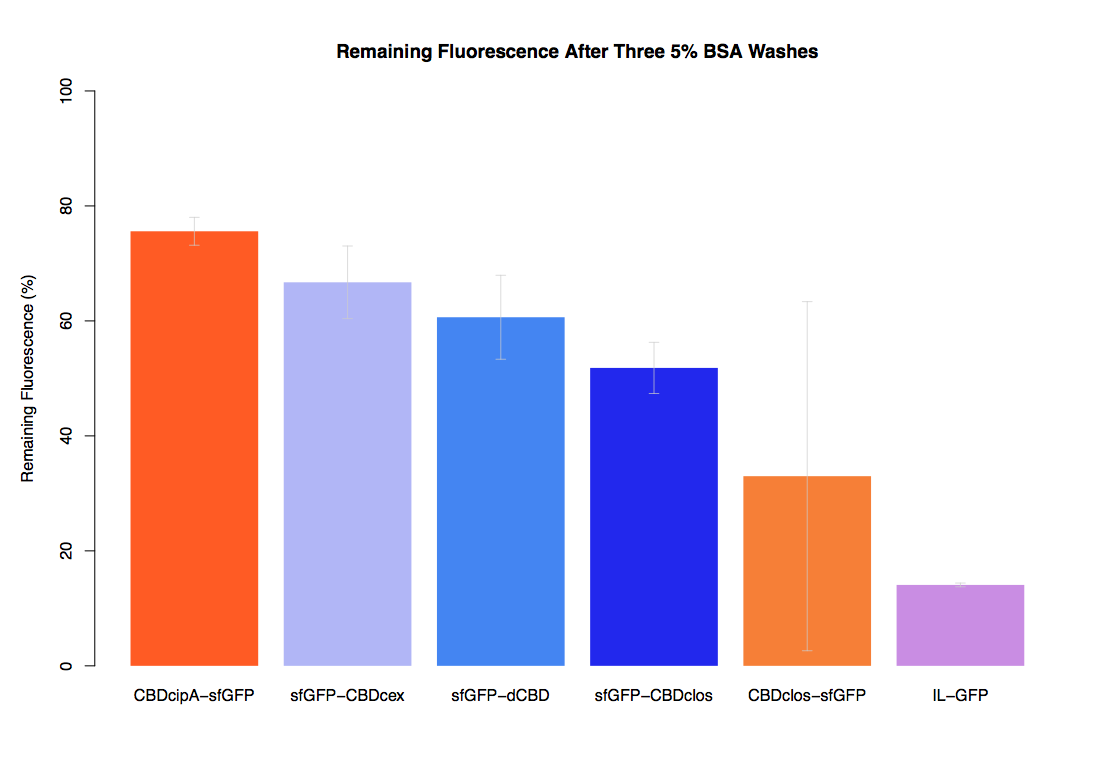

| + | The binding ability of this CBD to bacterial cellulose was characterised when fused to [https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1321337 sfGFP], relative to other CBDs fused to [https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1321337 sfGFP]. The binding ability was represented by the percentage fluorescence remaining from the sfGFP-CBD fusions bound to bacterial cellulose discs, when subjected to various washes (protocol [http://2014.igem.org/Team:Imperial/Protocols here]). It was determined that the dCBD-sfGFP fusion had the greatest binding ability in comparison to four other CBDs fused to sfGFP after three washes with both dH2O and 70% EtOH (see first two graphs). When washed with PBS and 5% BSA it had on average the third greatest ability to bind bacterial cellulose (third and fourth graphs below). | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:IC14_-_dH2Obplot1.png|700px|centre|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:IC14-EtOHbplot1.png|700px|centre|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:IC14-PBSbplot1.png|700px|centre|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:IC14-BSAbplot1.png|700px|centre|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | As part of our project, we needed to assay the metal binding capability of Phytochelatin (a general metal binding protein) fused to different CBDs (cellulose binding domains). The parts used for this assay are Phytochelatin+CBDcex, Phytochelatin+dCBD, CBDcipA+Phytochelatin, Phytochelatin alone and sfGFP+dCBD wash (only one wash). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Phytochelatin fused to our CBDs were bound onto cellulose that were dried in the bottom of 96-well plates and tested against 3 different metals (nickel, copper, zinc). | ||

| + | First, the fusion protein cell lysate was incubated overnight in the cellulose wells. Following this, the metal salt solutions are added in excess into the wells. | ||

| + | Finally, an EDTA step removes the bound metal ions into solution, and the metal concentration in solution is quantified by mass spectrometer. Multiple washes with PBS and water were done between each binding step, ensuring that the metal ions that are measured were released from the phytochelatin. | ||

| + | |||

| + | To evaluate if these CBD fusions were reusable, we re-applied metal ion solutions onto the same wells with the CBD fusions adhered. We washed the wells as before, then eluted with EDTA in the same manner. The results from the each elutions are shown below, with the final graph comparing between the first and second wash. We found along the way our bacterial cellulose alone had some metal chelating properties, as was also confirmed by our filtering set up with the dCBD-phytochelatin, but the second elution seems to show less background noise as the EDTA disrupts cellulose's natural binding to the metal ions. The full table of results are shown below as well. The full assay protocol can be found as ‘Metal binding assay protocol’ at this link: | ||

| + | http://2014.igem.org/Team:Imperial/Protocols | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | To read more about this assay and explanation of these results, please see: | ||

| + | http://2014.igem.org/Team:Imperial/Water_Filtration | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:IC14_first_wash_CBD_metal_conc.png|700px|centre|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:IC14_second_wash_CBD_metal_conc.png|700px|centre|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:IC14_Comparison_Nickel_conc_washes_CBDs.png|700px|centre|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:IC-2014_metalbindingtable.jpg|900px|centre|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Improvement== | ||

| + | ===BrownStanfordPrinctn 2019 BBa_K1321340 Experiments for Improvement in BBa_K3260036 === | ||

| + | |||

| + | In our experiments with BBa_K1321340, we took advantage of the endogenous linker and fused a hydrophobic domain to the N-terminus to create the part BBa_K3260031. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>BBa_K3260031 Single Layer Print:</p> | ||

| + | https://2019.igem.org/wiki/images/2/22/T--BrownStanfordPrinctn--test_one.mov | ||

| + | |||

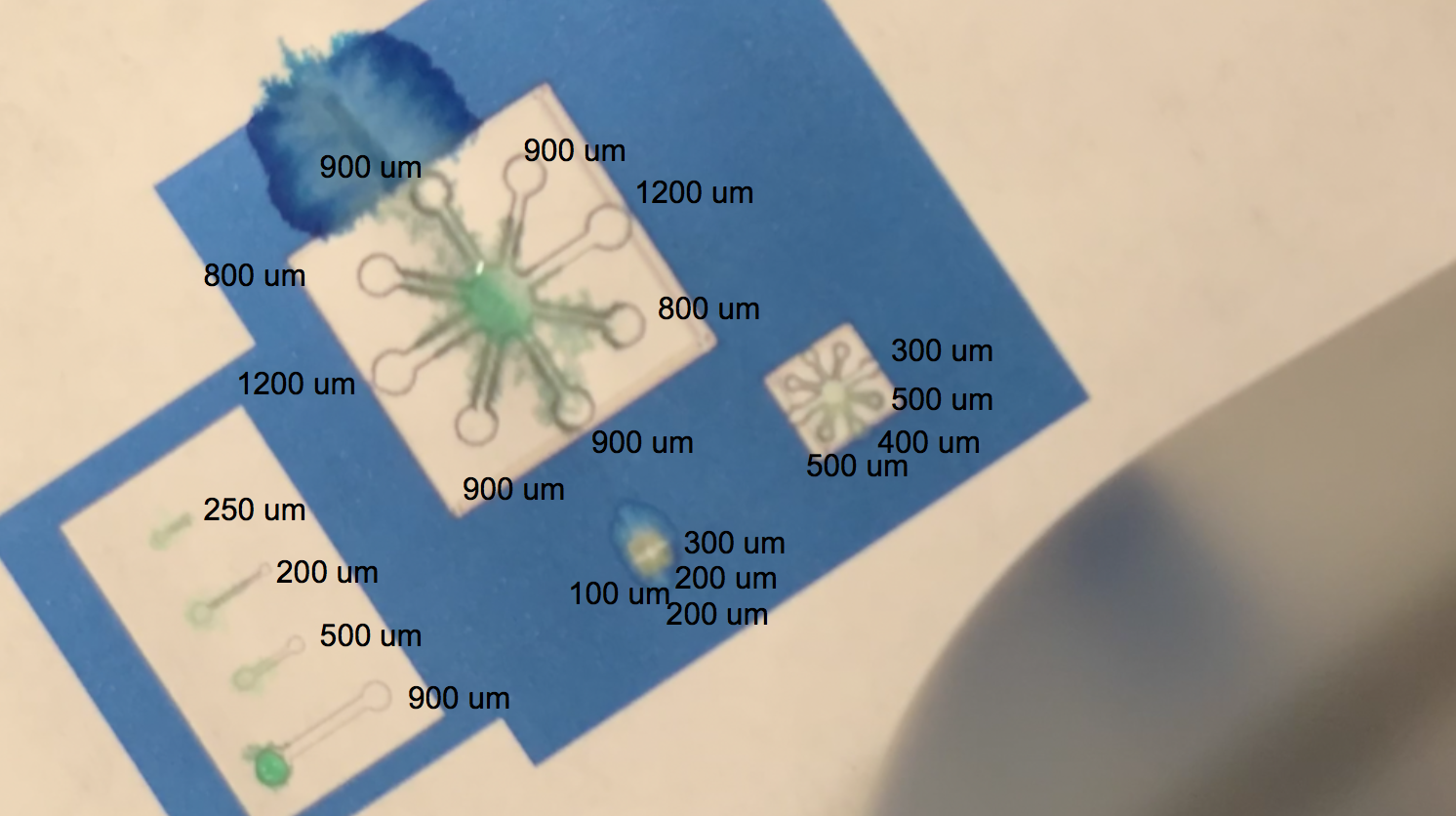

| + | <p>The video linked above shows one of our tests with printing with protein lysate. The lysate that we loaded into the black ink cartridge contained BBa_K3260031(our dCBD + our hydrophobic, or Radek) domain. Directly below is a labelling of this video with channel widths for each component in our testing template.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | https://2019.igem.org/wiki/images/a/a6/T--BrownStanfordPrinctn--video_one_labels.png | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>The blue regions are plain printer ink, while to the white sections in between the blue and the black outline of the channels are printed protein lysate. We can see on the range of straight, separated channels that the water efficiently wicked up the 250um wide channel and the 200um channel. On the largest “flower” template, the water flowed up the 800um and 900um channels. We also see a successful serendipitous negative control of our device once the water flows past the end of one of the 900um channels and starts penetrating the paper printed with blue ink. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This provides a nice contrast with the channel flow and illustrates that while the resolution of the channels isn’t extremely sharp, the dCBD is definitely bound to the cellulose substrate, and the hydrophobic protein is certainly performing its function. On the smaller scale flower channels, the water efficiently travels down the 100 - 500 um channels, which is indicative of its functionality on lower resolution ranges. | ||

| + | The effectiveness of the hydrophobic domain is only made possible by the binding affinity of BBa_K1321340, the dCBD. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </p><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Improvement by IISc-Bangalore 2021=== | ||

| + | This part was codon-optimized for expression in ''E. coli''. We attached this part to SpyCatcher002 to yield a SpyCatcher002-dCBD construct, which can be used for anchoring SpyTagged proteins onto a microcrystalline cellulose matrix. From structural predictions using AlphaFold as well as solubility tests, we found that the SpyCatcher002 and dCBD domains fold independently and do not inhibit each other's functionality. See [https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3765004 BBa_K3765004] and [https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3765012 BBa_K3765012] for more details. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Links== | ||

| + | |||

| + | 【1】https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3765004 | ||

| + | |||

| + | 【2】https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3765012 | ||

| + | |||

| − | |||

<!-- --> | <!-- --> | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | |||

<partinfo>BBa_K1321340 SequenceAndFeatures</partinfo> | <partinfo>BBa_K1321340 SequenceAndFeatures</partinfo> | ||

| Line 24: | Line 92: | ||

<partinfo>BBa_K1321340 parameters</partinfo> | <partinfo>BBa_K1321340 parameters</partinfo> | ||

<!-- --> | <!-- --> | ||

| + | |||

===References=== | ===References=== | ||

1. Linder, M.; Salovuori, I.; Ruohonen, L.; Teeri, T.T., 1996. Characterization of a Double Cellulose-binding Domain. SYNERGISTIC HIGH AFFINITY BINDING TO CRYSTALLINE CELLULOSE. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 271(35), pp.21268–21272. Available at: http://www.jbc.org/content/271/35/21268.full | 1. Linder, M.; Salovuori, I.; Ruohonen, L.; Teeri, T.T., 1996. Characterization of a Double Cellulose-binding Domain. SYNERGISTIC HIGH AFFINITY BINDING TO CRYSTALLINE CELLULOSE. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 271(35), pp.21268–21272. Available at: http://www.jbc.org/content/271/35/21268.full | ||

Latest revision as of 06:24, 21 October 2021

Double CBD (dCBD) with N-terminal linker

Double cellulose binding domain (dCBD) using two cellulose binding domains from Trichoderma reesei cellobiohydrolases, with an N-terminal linker and internal linker sequence between the two domains which is derived from the endogenous cellobiohydrolase linker sequence.

Please see below for AutoAnnotator information about the final protein product.

Usage and Biology

This part is based on the double cellulose-binding domain construct (CBDcbh2-linker-CBDcbh1) synthesised and characterised by Linder et al [http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.271.35.21268 (1)] who found that this double CBD had higher affinity for cellulose than either of the two CBDs on their own. The main difference is that our part contains an additional linker sequence on the N-terminus of the protein.

The two CBDs are from the fungus T. reesei (Hypocrea jecorina) Exocellobiohydrolase (Exoglucanase) I (cbh1), uniprot ID [http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P62694 P62694]; and Exocellobiohydrolase (Exoglucanase) II, uniprot ID [http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P07987 P07987] (cbh2); with a linker peptide between the two CBDs and at the N-terminus of the protein. Both linkers are the same amino acid sequence and are based on the endogenous linker sequences that exists in cbh1 and cbh2 genes. The linker sequence is PGANPPGTTTTSRPATTTGSSPGP which is the same as used by Linder et al [http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.271.35.21268 (1)]. The first three amino acids are from the cbh2 endogenous linker, and the rest is from the cbh1 endogenous linker. CBDcbh1 is placed C-terminal to CBDcbh2 because naturally CBDcbh1 is a C-terminal domain and CBDcbh2 is an N-terminal domain. Both CBDs are from the [http://www.cazy.org/CBM1.html CBM family 1]. The precise location of the CBD within the cbh genes was slightly different according to the uniprot annotations and the sequence used by Linder et al [http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.271.35.21268 (1)]; we chose to use the sequence from the paper since the protein was expressed and characterised successfully.

The binding ability of this CBD to bacterial cellulose was characterised when fused to sfGFP, relative to other CBDs fused to sfGFP. The binding ability was represented by the percentage fluorescence remaining from the sfGFP-CBD fusions bound to bacterial cellulose discs, when subjected to various washes (protocol [http://2014.igem.org/Team:Imperial/Protocols here]). It was determined that the dCBD-sfGFP fusion had the greatest binding ability in comparison to four other CBDs fused to sfGFP after three washes with both dH2O and 70% EtOH (see first two graphs). When washed with PBS and 5% BSA it had on average the third greatest ability to bind bacterial cellulose (third and fourth graphs below).

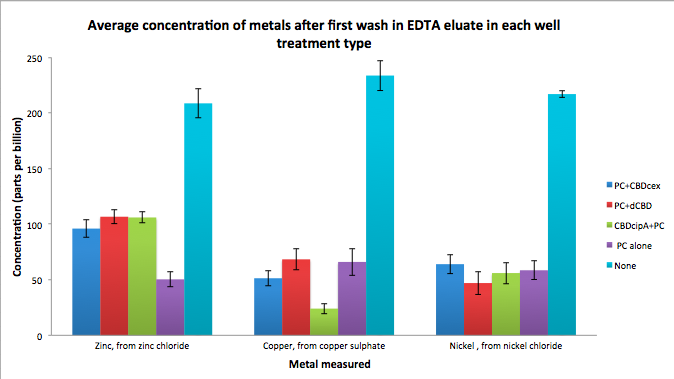

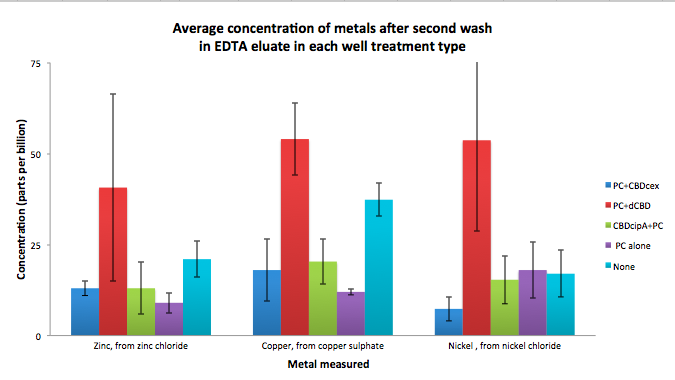

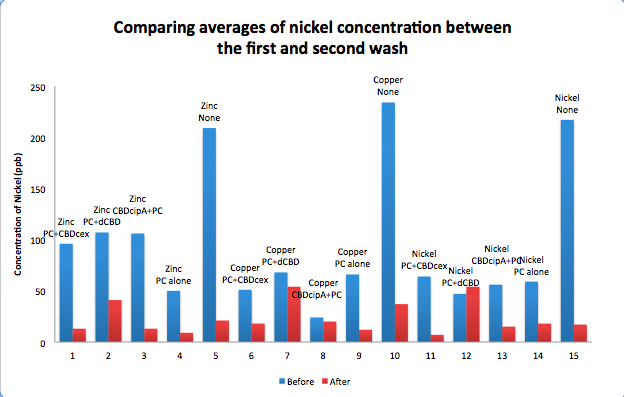

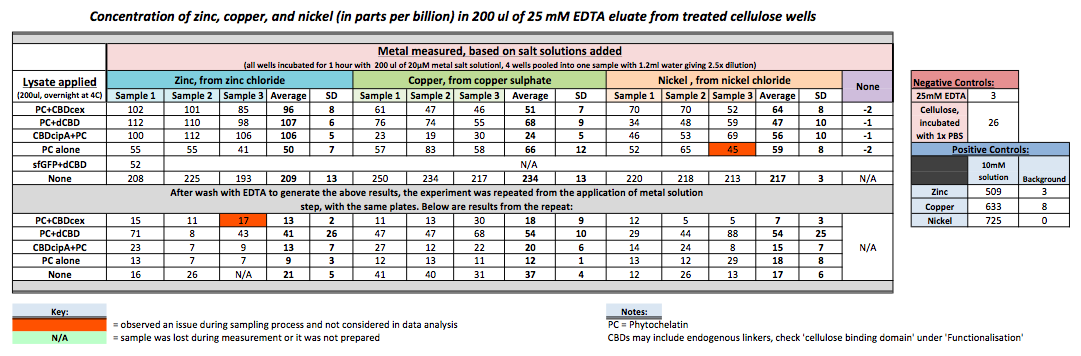

As part of our project, we needed to assay the metal binding capability of Phytochelatin (a general metal binding protein) fused to different CBDs (cellulose binding domains). The parts used for this assay are Phytochelatin+CBDcex, Phytochelatin+dCBD, CBDcipA+Phytochelatin, Phytochelatin alone and sfGFP+dCBD wash (only one wash).

Phytochelatin fused to our CBDs were bound onto cellulose that were dried in the bottom of 96-well plates and tested against 3 different metals (nickel, copper, zinc). First, the fusion protein cell lysate was incubated overnight in the cellulose wells. Following this, the metal salt solutions are added in excess into the wells. Finally, an EDTA step removes the bound metal ions into solution, and the metal concentration in solution is quantified by mass spectrometer. Multiple washes with PBS and water were done between each binding step, ensuring that the metal ions that are measured were released from the phytochelatin.

To evaluate if these CBD fusions were reusable, we re-applied metal ion solutions onto the same wells with the CBD fusions adhered. We washed the wells as before, then eluted with EDTA in the same manner. The results from the each elutions are shown below, with the final graph comparing between the first and second wash. We found along the way our bacterial cellulose alone had some metal chelating properties, as was also confirmed by our filtering set up with the dCBD-phytochelatin, but the second elution seems to show less background noise as the EDTA disrupts cellulose's natural binding to the metal ions. The full table of results are shown below as well. The full assay protocol can be found as ‘Metal binding assay protocol’ at this link: http://2014.igem.org/Team:Imperial/Protocols

To read more about this assay and explanation of these results, please see:

http://2014.igem.org/Team:Imperial/Water_Filtration

Improvement

BrownStanfordPrinctn 2019 BBa_K1321340 Experiments for Improvement in BBa_K3260036

In our experiments with BBa_K1321340, we took advantage of the endogenous linker and fused a hydrophobic domain to the N-terminus to create the part BBa_K3260031.

BBa_K3260031 Single Layer Print:

https://2019.igem.org/wiki/images/2/22/T--BrownStanfordPrinctn--test_one.mov

The video linked above shows one of our tests with printing with protein lysate. The lysate that we loaded into the black ink cartridge contained BBa_K3260031(our dCBD + our hydrophobic, or Radek) domain. Directly below is a labelling of this video with channel widths for each component in our testing template.

The blue regions are plain printer ink, while to the white sections in between the blue and the black outline of the channels are printed protein lysate. We can see on the range of straight, separated channels that the water efficiently wicked up the 250um wide channel and the 200um channel. On the largest “flower” template, the water flowed up the 800um and 900um channels. We also see a successful serendipitous negative control of our device once the water flows past the end of one of the 900um channels and starts penetrating the paper printed with blue ink. This provides a nice contrast with the channel flow and illustrates that while the resolution of the channels isn’t extremely sharp, the dCBD is definitely bound to the cellulose substrate, and the hydrophobic protein is certainly performing its function. On the smaller scale flower channels, the water efficiently travels down the 100 - 500 um channels, which is indicative of its functionality on lower resolution ranges. The effectiveness of the hydrophobic domain is only made possible by the binding affinity of BBa_K1321340, the dCBD.

Improvement by IISc-Bangalore 2021

This part was codon-optimized for expression in E. coli. We attached this part to SpyCatcher002 to yield a SpyCatcher002-dCBD construct, which can be used for anchoring SpyTagged proteins onto a microcrystalline cellulose matrix. From structural predictions using AlphaFold as well as solubility tests, we found that the SpyCatcher002 and dCBD domains fold independently and do not inhibit each other's functionality. See BBa_K3765004 and BBa_K3765012 for more details.

Links

【1】https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3765004

【2】https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K3765012

- 10COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[10]

- 12COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[12]

- 21COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[21]

- 23COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[23]

- 25COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[25]

- 1000COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[1000]

| Protein data table for BioBrick BBa_K1321340 automatically created by the BioBrick-AutoAnnotator version 1.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide sequence in RFC 25: (underlined part encodes the protein) ATGGCCGGC ... CTTACCGGTTAA ORF from nucleotide position 1 to 381 (excluding stop-codon) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Amino acid sequence: (RFC 25 scars in shown in bold, other sequence features underlined; both given below)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sequence features: (with their position in the amino acid sequence, see the list of supported features)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Amino acid composition:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Amino acid counting

| Biochemical parameters

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Plot for hydrophobicity, charge, predicted secondary structure, solvent accessability, transmembrane helices and disulfid bridges | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Codon usage

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alignments (obtained from PredictProtein.org) There were no alignments for this protein in the data base. The BLAST search was initialized and should be ready in a few hours. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predictions (obtained from PredictProtein.org) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| There were no predictions for this protein in the data base. The prediction was initialized and should be ready in a few hours. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The BioBrick-AutoAnnotator was created by TU-Munich 2013 iGEM team. For more information please see the documentation. If you have any questions, comments or suggestions, please leave us a comment. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

1. Linder, M.; Salovuori, I.; Ruohonen, L.; Teeri, T.T., 1996. Characterization of a Double Cellulose-binding Domain. SYNERGISTIC HIGH AFFINITY BINDING TO CRYSTALLINE CELLULOSE. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 271(35), pp.21268–21272. Available at: http://www.jbc.org/content/271/35/21268.full