Difference between revisions of "Part:BBa K3027000"

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

<p align="justify"> | <p align="justify"> | ||

| − | + | MVISAEKQTVILKMAADFNFYGKRLRATKLEVCDDISKMVYDTTKHSTAICDWLEANKPAKPKAAKVAKAIKNDERPEAAGIVSS TVEQWEVKQGKRFIITSIQNNTFPHKNFLASLEQYAQFIGADLLVSKFIYNKNGFQNGEGADGIRYDSAFDKYICNKNVFLNNRR FAFMAEINVLPTADYPLSGFAETATALNLEGLAIGAAKITAESVPALKGEIVRRMYSTGTATLKNYIQQKAGQKAEALHNFGALI VEFDEDGEFFVRQLETMDESGVFYDLNTCATPAGCYETTGHVLGLQYGDIHAEKLDEECAAASWGHGDTYGLVDILKPKYQFVHD VHDFTSRNHHNRASGVFLAKQYAAGRDKVLDDLIDTGRVLESMERDFSQTIIVESNHDLALSRWLDDRNANIKDDPANAELYHRL NAAIYGAIAEKDDTFNVLDYALRKVAGCEFNAIFLTTDQSFKIAGIECGVHGHNGINGSRGNPKQFKKLGKLNTGHTHTASIYGG VYTAGVTGSLDMGYNVGASSWTQTHIITYANGQRTLIDFKNGKFFA | |

</p> | </p> | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| Line 103: | Line 103: | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

| − | <img src="" width=" | + | <img src="https://2019.igem.org/wiki/images/e/e1/T--GO_Paris-Saclay--Fig10-A1-Blastx.png" width="100%" height="100%" align="center" alt="Blastx results"/> |

<p align="justify"> | <p align="justify"> | ||

Latest revision as of 01:55, 19 October 2019

A1 is a nuclease coming from T5 phage. We have demonstated that this biobrick can eliminate genomic DNA and thus be used to efficiently generate DNA-less chassis.

- 10COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[10]

- 12COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[12]

- 21COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[21]

- 23COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[23]

- 25COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[25]

- 1000COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[1000]

Nuclease_A1 sequence (556 amino acids):

MVISAEKQTVILKMAADFNFYGKRLRATKLEVCDDISKMVYDTTKHSTAICDWLEANKPAKPKAAKVAKAIKNDERPEAAGIVSS TVEQWEVKQGKRFIITSIQNNTFPHKNFLASLEQYAQFIGADLLVSKFIYNKNGFQNGEGADGIRYDSAFDKYICNKNVFLNNRR FAFMAEINVLPTADYPLSGFAETATALNLEGLAIGAAKITAESVPALKGEIVRRMYSTGTATLKNYIQQKAGQKAEALHNFGALI VEFDEDGEFFVRQLETMDESGVFYDLNTCATPAGCYETTGHVLGLQYGDIHAEKLDEECAAASWGHGDTYGLVDILKPKYQFVHD VHDFTSRNHHNRASGVFLAKQYAAGRDKVLDDLIDTGRVLESMERDFSQTIIVESNHDLALSRWLDDRNANIKDDPANAELYHRL NAAIYGAIAEKDDTFNVLDYALRKVAGCEFNAIFLTTDQSFKIAGIECGVHGHNGINGSRGNPKQFKKLGKLNTGHTHTASIYGG VYTAGVTGSLDMGYNVGASSWTQTHIITYANGQRTLIDFKNGKFFA

To characterize the nuclease, its CDS has been inserted in a plasmid under the control of an inducible promoter. This plasmid was then used to transform bacteria which will express the nuclease for the study.

Plasmid Description

The pBAD24 cloning vector contains an ampicillin resistance gene, the pBR322_origin for replication, an araC gene encoding the AraC transcriptional regulator and the arabinose-inducible PBAD promoter (also called Para). We modified plasmid pBAD24 to introduce two BsaI sites downstream the PBAD promoter to facilitate cloning using the Golden Gate technique. This new plasmid, named pBAD24-MoClo, allows type IIs cloning of a coding sequence (CDS) with the prefix AATG and the suffix GCTT.

The nuclease A1 gene (BBa_K3027000) was inserted in pBAD24-Moclo using the two BsaI sites to obtain the plasmid pBAD24-nuclease_A1.

In the absence of arabinose, AraC forms a homodimer that represses transcription of the gene beneath the control of PBAD. Arabinose modifies the conformation of AraC homodimer to activate PBAD-dependent transcription. AraC synthesis is also controlled by the presence of glucose in the media. At low glucose concentration, the adenylate cyclase produces cAMP, which associates with CRP to activate araC transcription. Therefore, maximum expression from the promoter PBAD is reached when bacteria are grown in the absence of glucose and the presence of arabinose.

Characterization Protocol

The E. coli KeioZ1F’ strain was transformed with pBAD24-nuclease_A1. The resulting strain was characterized as follows:

Strain KeioZ1F’ + pBAD24-nuclease_A1 was inoculated in 3 ml of LB supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/mL) and glucose (0.2 %) and grown overnight at 37°C with shaking. The next day, the culture was diluted in LB supplemented with ampicillin (but without glucose) in order to have an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) equal to 0.1. The culture was shaken at 37°C until OD600 =0.4. Expression of the nuclease was then induced by adding arabinose (0.2 %) to the media at time point t=0. OD600 was measured and the cell number was determined by spotting 10 μL of serial dilutions on agar plate (LB + ampicillin + glucose) at different time points: -30 min (i.e. 30 min prior to arabinose induction), +30 min (i.e. 30 min after arabinose induction), +90 min, +150 min and the “day after”. This protocol was performed at least five times during the summer to have a large amount of data. The control experiment was performed with the KeioZ1F’ strain transformed with pBAD24-MoClo (this plasmid does not carry the nuclease gene).

Results

Result 1: Expression of nuclease gene A1 inhibits bacterial growth and survival

Addition of arabinose to the growth media resulted in growth arrest for the strain expressing nuclease_A1 while the OD600 kept increasing for the strain carrying the control plasmid (pBAD24-MoClo). We observed that A1 nuclease expression stopped bacterial growth until at least to 150 min upon arabinose induction.

Result 2: Reduced genomic DNA recovery upon expression of nuclease gene A1

Next, we followed the impact of nuclease induction on bacterial genomic DNA (gDNA). Following addition of arabinose, one mL of culture was sampled at different times to extract gDNA. Figure 4A shows the results obtained using a Promega kit (cat A1120), following the manufacturer’s instructions except that RNase was not added. Figure 4B is another experiment where gDNA was extracted in the presence of RNase using a Macherey-Nagel kit . The KeioZ1F’ strain carrying pBAD24-MoClo was used as a control.

At all timepoints, gDNA and ribosomal RNA (rRNA) can be recovered from the control bacteria carrying plasmid pBAD24-MoClo. In contrast, as soon as 30 min after arabinose addition we could barely recover gDNA from cells carrying pBAD24-nuclease_A1, while rRNA was present in all samples (Figure 4A). In another experiment where RNase was added during gDNA isolation, we also observed that no gDNA could be recovered from cells expressing nuclease_A1 for 30 and 90 min (Figure 4B). Thus, induction of the expression of nuclease_A1 leads to the destruction of bacterial DNA.

Result 3: Reduced DNA staining with DAPI in cells expressing nuclease gene A1

To visualize whether cells expressing nuclease_A1 were still intact and whether they contained DNA that could be stained with DAPI, a microscopy study was performed using cell fixation and DAPI staining. Following arabinose addition, culture aliquots were taken at different time points (t = 0min, t = +30min, t = + 90min). Cells were fixed and stained according to the protocol “Fixation of cells and coloration with DAPI”. The control strain is the KeioZ1F’ strain transformed with pBAD24-MoClo.

Arabinose addition to the control cultures did not affect bacterial DNA staining with DAPI (Figure 5A). However, for those containing pBAD24-nuclease_A1, the addition of arabinose resulted in the DNA destruction in most of the bacteria already after 30 min (Figure 5B), consistent with the reduced gDNA recovery observed previously (Figure 4). After 90 min of nuclease induction only a minority of cells show some staining with DAPI. Therefore, within 30 min of expression of nuclease_A1, we generated bacterial cells free of DNA.

Result 4: Some bacterial cells survive following the expression of nuclease gene A1

When bacteria were incubated overnight with arabinose, some cells were able to survive and multiply, as witnessed by an increase in OD (Figure 6).

Therefore, some bacteria (or “cheaters”) did survive the nuclease induction. We collected two colonies from two independent induction experiments: the strains were called “Survivor 1” and “Survivor 4”. Next, we tested whether the “Survivor” strains changed phenotype compared to the original strain that was always maintained in medium with glucose (Figure 8 and 9): they no longer exhibited slowed growth or decreased survival when arabinose was added to the cells.

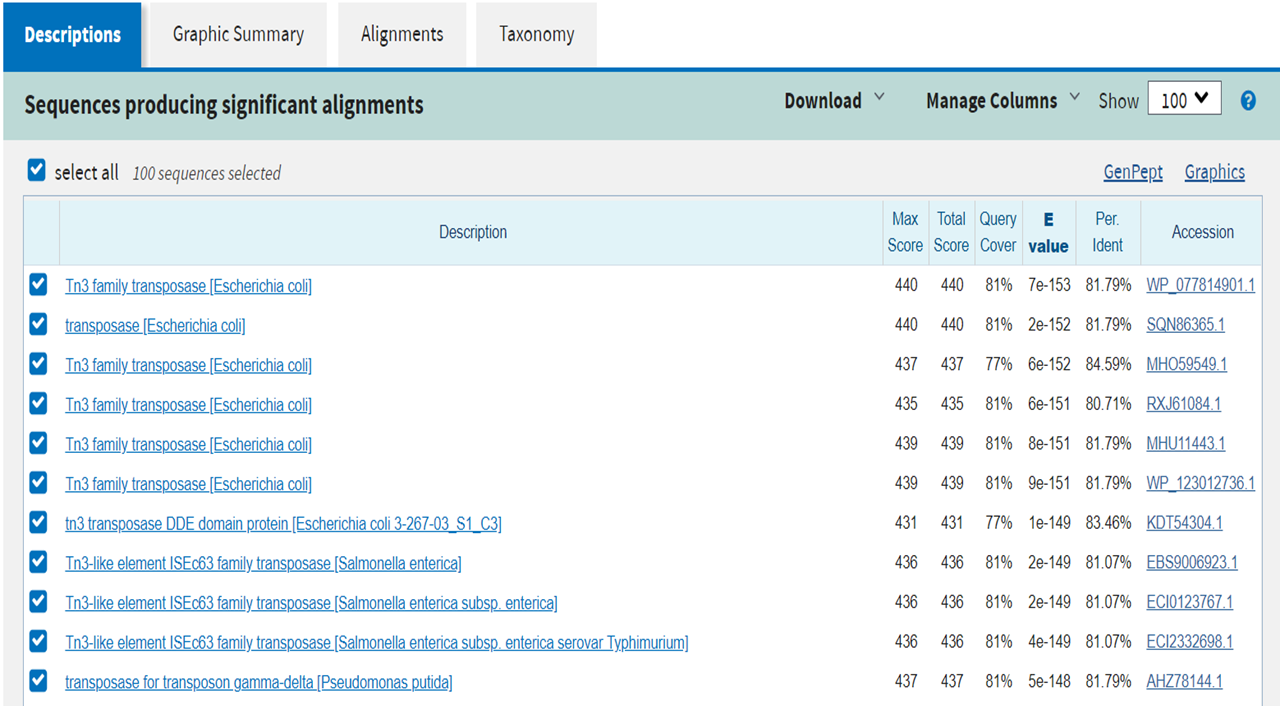

In order to understand how these bacteria were now able to escape death, we extracted plasmid DNA from the survivors and introduced it into strain KeioZ1F’. The resulting transformants were resistant to the negative effect of arabinose addition on growth, suggesting that the plasmids from survivors carry mutations disabling the nuclease gene or its expression. Sequence analysis of the plasmid recovered from “Survivor” 1 revealed a complete deletion of the A1 gene. For plasmid recovered from “Survivor 4” there were new DNA sequences inside the CDS of A1. These sequences were analysed with Blastx (Figure 10).

For survivor clone 4, we found a transposase inserted in the A1 CDS.

Both of the mutations explain why and how these survivors escaped death from the nuclease induction.

Conclusions

Taken together, our results show that expression of our new biobrick nuclease_A1 in E. coli leads to the destruction of bacterial genomic DNA, thereby generating DNA-free cells. Loss of the nuclease gene by deletion or gene inactivation through transposase insertion are some mechanisms that can explain that 0.1% of cells escape killing. Despite these limitations, our new biobrick is a promising tool that could be used in the future for genetic containment.