Difference between revisions of "Part:BBa K1980003"

(→Description) |

|||

| (23 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

__NOTOC__ | __NOTOC__ | ||

<partinfo>BBa_K1980003 short</partinfo> | <partinfo>BBa_K1980003 short</partinfo> | ||

| − | + | ==Description== | |

| − | MymT is a small prokaryotic copper metallothein discovered in <i>Mycobacterium tuberculosis</i>. It can bind up to 7 copper ions but has a preference for 4-6. This version has a C terminal sfGFP with a C terminal hexahistidine tag for purification. The MymT and sfGFP are separated by a short hydrophilic, flexible linker. | + | MymT is a small prokaryotic copper metallothein discovered in <i>Mycobacterium tuberculosis</i>. It can bind up to 7 copper ions but has a preference for 4-6. This version has a C terminal sfGFP with a C terminal hexahistidine tag for purification. The MymT and sfGFP are separated by a short hydrophilic, flexible linker. |

| − | <p> | + | <html><p> |

| − | A form of MymT was already in the registry at the start of our project (https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K190020) but it was | + | A form of MymT was already in the registry at the start of our project (<a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K190020">BBa_K190020</a>) but it was not codon optimised to <i>E. coli</i> and we saw no evidence that it had been used. We codon optimised it and added a C terminal his tag in part (<a href="https://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1980002">BBa_K1980002</a>) and here added both a sfGFP and we obtained provisional data using fluorescence lifetime microscopy suggesting copper-binding <i>in vivo</i>.</p> |

| + | </html> | ||

<span class='h3bb'>Sequence and Features:</span> | <span class='h3bb'>Sequence and Features:</span> | ||

<partinfo>BBa_K1980003 SequenceAndFeatures</partinfo> | <partinfo>BBa_K1980003 SequenceAndFeatures</partinfo> | ||

| + | ==Usage and Biology== | ||

| − | + | <p> | |

| − | <p> Our project aimed to detect and chelate dietary copper as a treatment for Wilson's Disease, a copper accumulation disorder. | + | Our project aimed to detect and chelate dietary copper as a treatment for Wilson's Disease, a copper accumulation disorder. |

We decided that the ideal copper chelation protein would have these properties: | We decided that the ideal copper chelation protein would have these properties: | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

| Line 22: | Line 24: | ||

<p> MymT is believed to bind up to 7 copper ions but has a preference for 4-6.<sup>(1)</sup> | <p> MymT is believed to bind up to 7 copper ions but has a preference for 4-6.<sup>(1)</sup> | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

| − | + | <p>Here MymT is encoded with a C terminal sfGFP, separated by a short linker (GlySerGlySerGlySer) to avoid misfolding, that has a C terminal histag for purification.</p> | |

<!-- --> | <!-- --> | ||

| Line 28: | Line 30: | ||

<p> We cloned MymTsfGFP from Gblock into the shipping vector then transferred it into the pBAD, arabinose-inducible commercial expression vector.</p> | <p> We cloned MymTsfGFP from Gblock into the shipping vector then transferred it into the pBAD, arabinose-inducible commercial expression vector.</p> | ||

| − | <p>We were unable however to detect copper chelation activity of | + | ===Absorbance Assay=== |

| − | <p>We purified | + | |

| + | <p>We were unable however to detect copper chelation activity of MymT when expressed from pBAD in MG1655 <i>E. coli</i> strain, using an absorbance assay. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | The assay used was the reagent Bathocuproine disulphonic Acid (BCS). BCS is colourless in the absence of Cu<sup>+</sup> but upon exposure to Cu<sup>+</sup>, BCS forms complexes with Cu<sup>+</sup> and absorbs strongly in the 480nm range. In our assays, at concentrations of 50µg/mL, the 480nm absorbance varied linearly with the Cu+ concentration from the detection limit of around 1µM Cu<sup>+</sup>, to approximately 20µM Cu<sup>+</sup>. As not only MymT and Csp1 bind copper in the Cu<sup>+</sup> form, but the assay also requires singly charged copper, the assays were optimised to include a suitable about of mild reducing agent to ensure reduction of the added CuSO<sub>4</sub> (releases Cu<sup>2+</sup>) to Cu<sup>+</sup>. After trying L(+)-Ascorbate and DL-Dithiothreitol, and L-Glutathione as candidates, L-Glutathione was selected as it was both mild enough to not damage biological material and efficient at reducing Cu<sup>2+</sup>. At >2-3 times the concentration of Cu<sup>2+</sup> in solution, L-Glutathione had maximum reductive activity against Cu<sup>2+</sup>.</p> | ||

| + | <p> Modelling by our team suggested that this was because insufficient protein could be expressed to chelate the amount needed to be detectable on the assay (1μM detection limit).</p> | ||

| + | <p>We purified this part, from MG1655 cells expressign MymT sfrom pBad, suing Nickel affinity chromatography followed by dialysis. However were unable to detect copper chelation with the assay in our purified extracts when compared to a his-tagged GFP control. This is possibly because the flexible linked was susceptible to cleavage by proteases in the lysate meaning the protein we purified lacked the chelator portion. | ||

===FLIM=== | ===FLIM=== | ||

| − | + | ||

We discovered a paper by Hötzer et al<sup>(2)</sup> that described how His-tagged GFP can be quenched by a copper ion binding to this His tag leading to a reduction in the fluorescence lifetime (the time the fluorophore spends in the excited state before returning to the ground state by emitting a photon.) They speculated that this could potentially be used as a <i>in vivo</i> copper assay. | We discovered a paper by Hötzer et al<sup>(2)</sup> that described how His-tagged GFP can be quenched by a copper ion binding to this His tag leading to a reduction in the fluorescence lifetime (the time the fluorophore spends in the excited state before returning to the ground state by emitting a photon.) They speculated that this could potentially be used as a <i>in vivo</i> copper assay. | ||

| − | + | ||

https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/3/32/FLIM_diagram_sam_oxford_2016.png | https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/3/32/FLIM_diagram_sam_oxford_2016.png | ||

| − | + | ||

As we had His-tagged our chelator-sfGFP constructs we were curious to see if this technique could be applied to our parts to measure copper chelation <i>in vivo</i> by our parts. We believe that two possibilities were likely: | As we had His-tagged our chelator-sfGFP constructs we were curious to see if this technique could be applied to our parts to measure copper chelation <i>in vivo</i> by our parts. We believe that two possibilities were likely: | ||

| − | + | ||

<ol> | <ol> | ||

<li>Copper chelation by the chelator reduces the free copper concentration inside the cell meaning that less binds to the His tag and the fluorescence lifetime will be greater than a His-tagged sfGFP control</li> | <li>Copper chelation by the chelator reduces the free copper concentration inside the cell meaning that less binds to the His tag and the fluorescence lifetime will be greater than a His-tagged sfGFP control</li> | ||

<li>Copper chelation by the chelator would allow additional quenching if copper was bound within the quenching radius of the fluorophore leading to a reduction in fluorescence lifetime compare with a sfGFP control</li> | <li>Copper chelation by the chelator would allow additional quenching if copper was bound within the quenching radius of the fluorophore leading to a reduction in fluorescence lifetime compare with a sfGFP control</li> | ||

</ol> | </ol> | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | Lacking access to a fluorescence lifetime microscope ourselves we contacted Cardiff iGEM who had a FLIM machine in their bioimaging unit | + | Lacking access to a fluorescence lifetime microscope ourselves we contacted Cardiff iGEM who had a FLIM machine in their bioimaging unit. |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | We sent Cardiff iGEM our parts MymTsfGFP in pBAD and pCopA CueR sfGFP (as a control) in live MG1655 <i>E. coli</i> in agar tubes. Cardiff grew them overnight in 5ml of LB with 5μM copper with and without 2mM arabinose. | |

| − | We sent Cardiff iGEM our parts MymTsfGFP in pBAD and pCopA CueR sfGFP (as a control) in live MG1655 <i>E. coli</i> in agar tubes. Cardiff grew them overnight in 5ml of LB with | + | |

| − | + | The imaging unit spread each strain on slides and measured the fluorescence lifetime of three areas on each slide. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | The imaging unit spread each strain on slides and measured the fluorescence lifetime of three areas on each slide. | + | |

<p> (Acquisition parameters: using the x63 water immersion objective with excitation at 483nm (71% intensity, pulse rate 40MHz) and emission via a BP500-550 filter. Scan resolution at 512 x 512 pixels at pixel size of 0.26 microns/pixel, 1AU pinhole. Counts of >1000 per lifetime recording.) | <p> (Acquisition parameters: using the x63 water immersion objective with excitation at 483nm (71% intensity, pulse rate 40MHz) and emission via a BP500-550 filter. Scan resolution at 512 x 512 pixels at pixel size of 0.26 microns/pixel, 1AU pinhole. Counts of >1000 per lifetime recording.) | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | FLIM images from one section of each slide: | |

https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/5/5d/FLIM_images_sam_oxford_2016.png | https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/5/5d/FLIM_images_sam_oxford_2016.png | ||

| − | + | ||

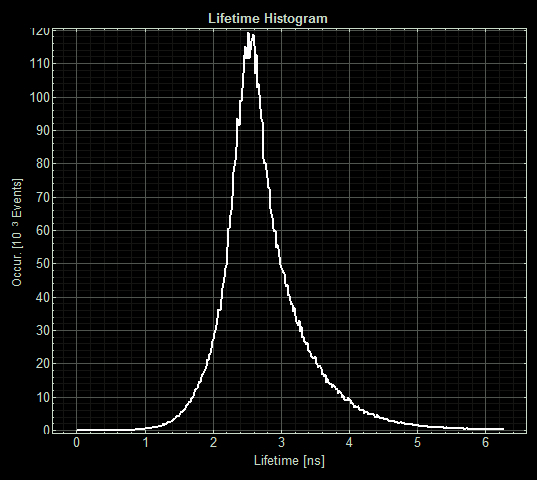

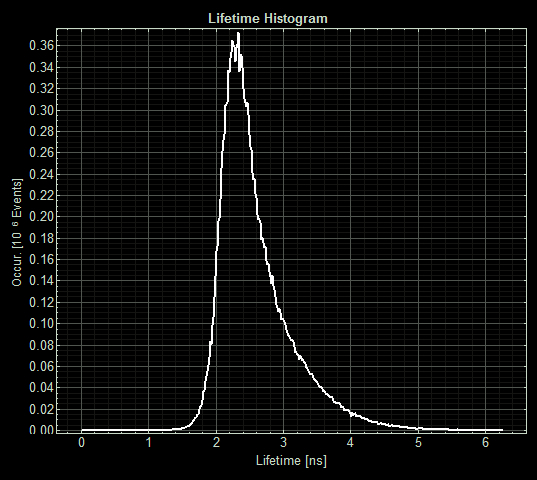

| − | As expected the pCopA CueR sfGFP control was fluorescent, with and without arabinose, with the mean fluorescence lifetime a consistent 2.6ns. | + | As expected the pCopA CueR sfGFP control was fluorescent, with and without arabinose, with the mean fluorescence lifetime a consistent 2.6ns. |

| − | + | ||

| − | When MymTsfGFP was induced the mean lifetime decreased to 2.3ns. As MymTsfGFP is was observed to be reliably expressed and because MymT is a small copper cluster separated form sfGFP by a small linker we believe that this represents additional quenching of the fluorphore by MymT-bound copper showing <i>in vivo</i> copper chelation. | + | When MymTsfGFP was induced the mean lifetime decreased to 2.3ns. As MymTsfGFP is was observed to be reliably expressed and because MymT is a small copper cluster separated form sfGFP by a small linker we believe that this represents additional quenching of the fluorphore by MymT-bound copper showing <i>in vivo</i> copper chelation. |

| − | [[Image:T--Oxford--Sam-FLIM-sfGFP.jpg|400px|thumb|left|Histogram showing the fluorescence lifetime of sfGFP at | + | [[Image:T--Oxford--Sam-FLIM-sfGFP.jpg|400px|thumb|left|Histogram showing the fluorescence lifetime of sfGFP at 5μM copper]] |

| − | [[Image:T--Oxford--Sam-FLIM-MymTsfGFP.jpg|400px|thumb|right|Histogram showing the fluorescence lifetime of Csp1sfGFP at | + | [[Image:T--Oxford--Sam-FLIM-MymTsfGFP.jpg|400px|thumb|right|Histogram showing the fluorescence lifetime of Csp1sfGFP at 5μM copper]] |

<!-- Uncomment this to enable Functional Parameter display | <!-- Uncomment this to enable Functional Parameter display | ||

===Functional Parameters=== | ===Functional Parameters=== | ||

| Line 100: | Line 106: | ||

| + | ==References== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

(1) Ben Gold, Haiteng Deng, Ruslana Bryk, Diana Vargas, David Eliezer, Julia Roberts, | (1) Ben Gold, Haiteng Deng, Ruslana Bryk, Diana Vargas, David Eliezer, Julia Roberts, | ||

Xiuju Jiang, & Carl Nathan (2009) “Identification of a Copper-Binding Metallothionein in Pathogenic Mycobacteria” Nat Chem Biol. | Xiuju Jiang, & Carl Nathan (2009) “Identification of a Copper-Binding Metallothionein in Pathogenic Mycobacteria” Nat Chem Biol. | ||

| − | 2008 October ; 4(10): 609–616. doi:10.1038/nchembio.109. | + | 2008 October ; 4(10): 609–616. doi:10.1038/nchembio.109. |

| − | + | ||

(2) Hötzer B., Ivanov R., Altmeier S., Kappl R., Jung G., (2011) "Determination of copper(II) ion concentration by lifetime measurements of green fluorescent protein." Journal of Fluorescence, 21(6), pp. 2143-2153. doi: 10.1007/s10895-011-0916-1 | (2) Hötzer B., Ivanov R., Altmeier S., Kappl R., Jung G., (2011) "Determination of copper(II) ion concentration by lifetime measurements of green fluorescent protein." Journal of Fluorescence, 21(6), pp. 2143-2153. doi: 10.1007/s10895-011-0916-1 | ||

| − | |||

Latest revision as of 21:20, 24 October 2016

MymT sfGFP

Description

MymT is a small prokaryotic copper metallothein discovered in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It can bind up to 7 copper ions but has a preference for 4-6. This version has a C terminal sfGFP with a C terminal hexahistidine tag for purification. The MymT and sfGFP are separated by a short hydrophilic, flexible linker.

A form of MymT was already in the registry at the start of our project (BBa_K190020) but it was not codon optimised to E. coli and we saw no evidence that it had been used. We codon optimised it and added a C terminal his tag in part (BBa_K1980002) and here added both a sfGFP and we obtained provisional data using fluorescence lifetime microscopy suggesting copper-binding in vivo.

Sequence and Features:

- 10COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[10]

- 12COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[12]

- 21INCOMPATIBLE WITH RFC[21]Illegal XhoI site found at 595

- 23COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[23]

- 25COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[25]

- 1000COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[1000]

Usage and Biology

Our project aimed to detect and chelate dietary copper as a treatment for Wilson's Disease, a copper accumulation disorder. We decided that the ideal copper chelation protein would have these properties:

- Should be able to bind multiple copper ions per peptide to increase the efficient use of cell resources.

- They should be from the prokaryotic domain because eukaryotic proteins can have expression issues in Escherichia coli.

MymT is a small prokaryotic metallothein discovered in Mycobacterium tuberculosis by Gold et al.(1). It is believed that the protein may help the bacterium survive copper toxicity.

MymT is believed to bind up to 7 copper ions but has a preference for 4-6.(1)

Here MymT is encoded with a C terminal sfGFP, separated by a short linker (GlySerGlySerGlySer) to avoid misfolding, that has a C terminal histag for purification.

Experience

We cloned MymTsfGFP from Gblock into the shipping vector then transferred it into the pBAD, arabinose-inducible commercial expression vector.

Absorbance Assay

We were unable however to detect copper chelation activity of MymT when expressed from pBAD in MG1655 E. coli strain, using an absorbance assay.

The assay used was the reagent Bathocuproine disulphonic Acid (BCS). BCS is colourless in the absence of Cu+ but upon exposure to Cu+, BCS forms complexes with Cu+ and absorbs strongly in the 480nm range. In our assays, at concentrations of 50µg/mL, the 480nm absorbance varied linearly with the Cu+ concentration from the detection limit of around 1µM Cu+, to approximately 20µM Cu+. As not only MymT and Csp1 bind copper in the Cu+ form, but the assay also requires singly charged copper, the assays were optimised to include a suitable about of mild reducing agent to ensure reduction of the added CuSO4 (releases Cu2+) to Cu+. After trying L(+)-Ascorbate and DL-Dithiothreitol, and L-Glutathione as candidates, L-Glutathione was selected as it was both mild enough to not damage biological material and efficient at reducing Cu2+. At >2-3 times the concentration of Cu2+ in solution, L-Glutathione had maximum reductive activity against Cu2+.

Modelling by our team suggested that this was because insufficient protein could be expressed to chelate the amount needed to be detectable on the assay (1μM detection limit).

We purified this part, from MG1655 cells expressign MymT sfrom pBad, suing Nickel affinity chromatography followed by dialysis. However were unable to detect copper chelation with the assay in our purified extracts when compared to a his-tagged GFP control. This is possibly because the flexible linked was susceptible to cleavage by proteases in the lysate meaning the protein we purified lacked the chelator portion.

FLIM

We discovered a paper by Hötzer et al(2) that described how His-tagged GFP can be quenched by a copper ion binding to this His tag leading to a reduction in the fluorescence lifetime (the time the fluorophore spends in the excited state before returning to the ground state by emitting a photon.) They speculated that this could potentially be used as a in vivo copper assay.

As we had His-tagged our chelator-sfGFP constructs we were curious to see if this technique could be applied to our parts to measure copper chelation in vivo by our parts. We believe that two possibilities were likely:

- Copper chelation by the chelator reduces the free copper concentration inside the cell meaning that less binds to the His tag and the fluorescence lifetime will be greater than a His-tagged sfGFP control

- Copper chelation by the chelator would allow additional quenching if copper was bound within the quenching radius of the fluorophore leading to a reduction in fluorescence lifetime compare with a sfGFP control

Lacking access to a fluorescence lifetime microscope ourselves we contacted Cardiff iGEM who had a FLIM machine in their bioimaging unit.

We sent Cardiff iGEM our parts MymTsfGFP in pBAD and pCopA CueR sfGFP (as a control) in live MG1655 E. coli in agar tubes. Cardiff grew them overnight in 5ml of LB with 5μM copper with and without 2mM arabinose.

The imaging unit spread each strain on slides and measured the fluorescence lifetime of three areas on each slide. <p> (Acquisition parameters: using the x63 water immersion objective with excitation at 483nm (71% intensity, pulse rate 40MHz) and emission via a BP500-550 filter. Scan resolution at 512 x 512 pixels at pixel size of 0.26 microns/pixel, 1AU pinhole. Counts of >1000 per lifetime recording.)

FLIM images from one section of each slide:

As expected the pCopA CueR sfGFP control was fluorescent, with and without arabinose, with the mean fluorescence lifetime a consistent 2.6ns.

When MymTsfGFP was induced the mean lifetime decreased to 2.3ns. As MymTsfGFP is was observed to be reliably expressed and because MymT is a small copper cluster separated form sfGFP by a small linker we believe that this represents additional quenching of the fluorphore by MymT-bound copper showing in vivo copper chelation.

References

(1) Ben Gold, Haiteng Deng, Ruslana Bryk, Diana Vargas, David Eliezer, Julia Roberts, Xiuju Jiang, & Carl Nathan (2009) “Identification of a Copper-Binding Metallothionein in Pathogenic Mycobacteria” Nat Chem Biol. 2008 October ; 4(10): 609–616. doi:10.1038/nchembio.109.

(2) Hötzer B., Ivanov R., Altmeier S., Kappl R., Jung G., (2011) "Determination of copper(II) ion concentration by lifetime measurements of green fluorescent protein." Journal of Fluorescence, 21(6), pp. 2143-2153. doi: 10.1007/s10895-011-0916-1