Difference between revisions of "Part:BBa K1321005"

| (4 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

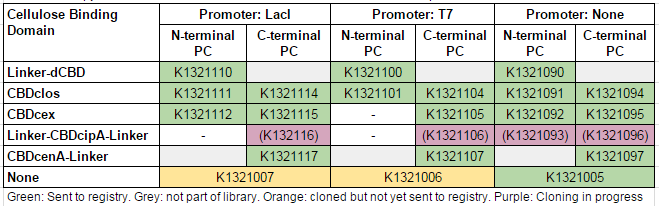

| − | We used this part to create a library of different cellulose-binding domains fused to phytochelatin | + | We used this part to create a library of different cellulose-binding domains fused to phytochelatin ([http://2014.igem.org/Team:Imperial/Functionalisation project page]) as shown in the table below: |

| − | + | [[File:IC14-PC-part-table.PNG]] | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | As part of our project, we needed to assay the metal binding capability of our Phytochelatins whilst fused to CBDs (cellulose binding domains). The parts used for this assay are | |

| − | + | Phytochelatin+CBDcex, Phytochelatin+dCBD, CBDcipA+Phytochelatin, Phytochelatin alone and sfGFP+dCBD wash (only one wash). | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Phytochelatin fused to our CBDs were bound onto cellulose that were dried in the bottom of 96-well plates and tested against 3 different metals (nickel, copper, zinc). | |

| − | + | First, the fusion protein cell lysate was incubated overnight in the cellulose wells. Following this, the metal salt solutions are added in excess into the wells. | |

| − | + | Finally, an EDTA step removes the bound metal ions into solution, and the metal concentration in solution is quantified by mass spectrometer. Multiple washes with PBS and water were done between each binding step, ensuring that the metal ions that are measured were released from the phytochelatin. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | To evaluate if these CBD fusions were reusable, we re-applied metal ion solutions onto the same wells with the CBD fusions adhered. We washed the wells as before, then eluted with EDTA in the same manner. The results from the each elutions are shown below, with the final graph comparing between the first and second wash. We found along the way our bacterial cellulose alone had some metal chelating properties, as was also confirmed by our filtering set up with the dCBD-phytochelatin, but the second elution seems to show less background noise as the EDTA disrupts cellulose's natural binding to the metal ions. The full table of results are shown below as well. The full assay protocol can be found as ‘Metal binding assay protocol’ at this link: | |

| − | + | http://2014.igem.org/Team:Imperial/Protocols | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | To read more about this assay and explanation of these results, please see: | |

| − | + | http://2014.igem.org/Team:Imperial/Water_Filtration | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | [[File:IC14_first_wash_CBD_metal_conc.png|700px|left|]] | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | [[File:IC14_second_wash_CBD_metal_conc.png|700px|left|]] | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | [[File:IC14_Comparison_Nickel_conc_washes_CBDs.png|700px|left|]] | |

| − | + | ||

| + | [[File:IC-2014_metalbindingtable.jpg|900px|left|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

===Sequence and Features=== | ===Sequence and Features=== | ||

Latest revision as of 04:33, 2 November 2014

Synthetic Phytochelatin EC(20) RFC[25]

Heavy metal-binding synthetic phytochelatin EC20 in Freiburg format (RFC[25]) to allow for easy use in fusion proteins.

Usage and Biology

| Ion | Approximate adsorption increase |

| Zn2+ | 219 % |

| Pb2+ | 210 % |

| Cu2+ | 76 % |

| Cd2+ | 59 % |

| Ni2+ | 45 % |

| Mn2+ | 31 % |

| Co2+ | marginal |

Synthetic phytochelatins are analogues of phytochelatins (PCs); cysteine-rich peptides of the general structure (γ-GluCys)n-Gly (n~2-5) which bind and sequester heavy metals, with a role in detoxification (1). PCs are found mainly in plants but also in other organisms including diatoms, fungi, algae (including cyanobacteria) and some invertebrates (1, 2). Natively, the PCs are enzymatically synthesized by phytochelatin synthase (PCS) from a glutathione (GSH) precursor and the amino acids in the resulting peptide are linked by the non-standard gamma peptide bonds (1, 2). However, genetically encoded analogues (containing normal alpha-peptide bonds) of different number Glu-Cys (EC) repeats have been characterised, with the EC20 having the highest binding (3).

The main metal PCs confer tolerance to is Cadmium (1) with a reported stoichiometry of 10 Cd2+ per peptide (3). EC20 peptide has still showed good metal ion binding whilst fused to a cellulose binding domain (CBD) for water purification (4) and when anchored to bacterial cell membrane to confer Cd2+ tolerance (3, 5). PC EC20 has also been shown to bind many more heavy metals. For example, when displayed on the surface of Cupriavidus metallidurans, the cells capacity to adsorb ions increased by 31 to 219% depending on the ion (table 1, 6). These binding properties of PC EC20 have been utilised in applications including a regeneratable biosensor of Hg2+, Cd2+, Pb2+, Cu2+ and Zn2+ ions to 100 fM–10 mM (7), and to target CdSe/ZnS quantum dots to streptavidin expressing HeLa cells when biotinylated (8).

We used this part to create a library of different cellulose-binding domains fused to phytochelatin ([http://2014.igem.org/Team:Imperial/Functionalisation project page]) as shown in the table below:

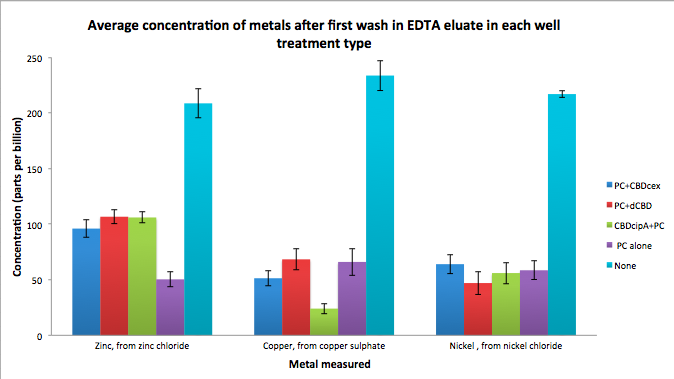

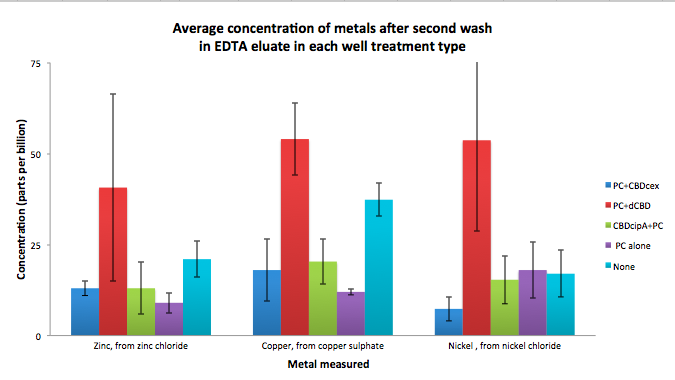

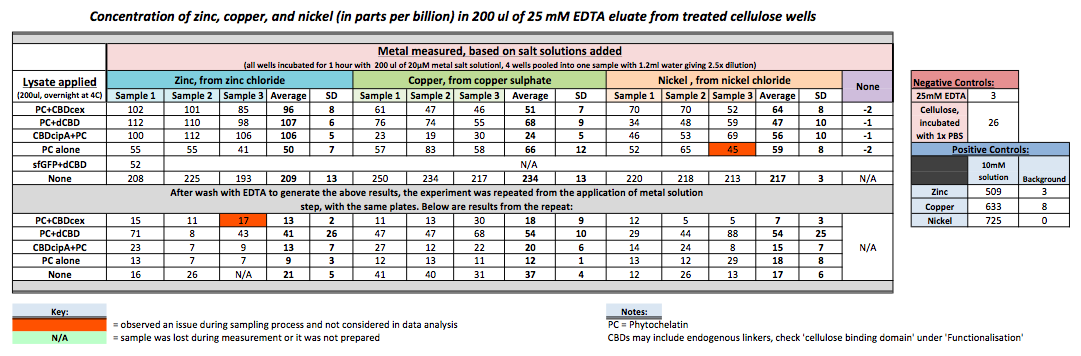

As part of our project, we needed to assay the metal binding capability of our Phytochelatins whilst fused to CBDs (cellulose binding domains). The parts used for this assay are

Phytochelatin+CBDcex, Phytochelatin+dCBD, CBDcipA+Phytochelatin, Phytochelatin alone and sfGFP+dCBD wash (only one wash).

Phytochelatin fused to our CBDs were bound onto cellulose that were dried in the bottom of 96-well plates and tested against 3 different metals (nickel, copper, zinc). First, the fusion protein cell lysate was incubated overnight in the cellulose wells. Following this, the metal salt solutions are added in excess into the wells. Finally, an EDTA step removes the bound metal ions into solution, and the metal concentration in solution is quantified by mass spectrometer. Multiple washes with PBS and water were done between each binding step, ensuring that the metal ions that are measured were released from the phytochelatin.

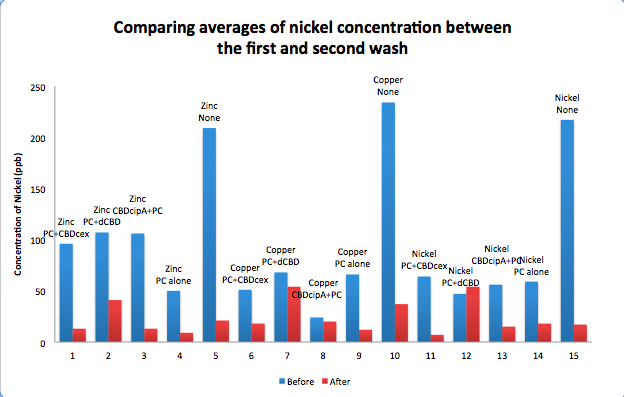

To evaluate if these CBD fusions were reusable, we re-applied metal ion solutions onto the same wells with the CBD fusions adhered. We washed the wells as before, then eluted with EDTA in the same manner. The results from the each elutions are shown below, with the final graph comparing between the first and second wash. We found along the way our bacterial cellulose alone had some metal chelating properties, as was also confirmed by our filtering set up with the dCBD-phytochelatin, but the second elution seems to show less background noise as the EDTA disrupts cellulose's natural binding to the metal ions. The full table of results are shown below as well. The full assay protocol can be found as ‘Metal binding assay protocol’ at this link: http://2014.igem.org/Team:Imperial/Protocols

To read more about this assay and explanation of these results, please see:

http://2014.igem.org/Team:Imperial/Water_Filtration

Sequence and Features

- 10COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[10]

- 12COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[12]

- 21COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[21]

- 23COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[23]

- 25COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[25]

- 1000COMPATIBLE WITH RFC[1000]

References

1. Cobbett, C. & Goldsbrough, P. (2002) Phytochelatins and metallothioneins: roles in heavy metal detoxification and homeostasis. Annual review of plant biology. 53, 159–182.

2. Rea, P.A. (2012) Phytochelatin synthase: of a protease a peptide polymerase made. Physiologia plantarum. 145 (1), 154–164.

3.Bae, W., Chen, W., Mulchandani, A. & Mehra, R.K. (2000) Enhanced bioaccumulation of heavy metals by bacterial cells displaying synthetic phytochelatins. Biotechnology and bioengineering. 70 (5), 518–524.

4. Xu, Z., Bae, W., Mulchandani, A., Mehra, R.K., et al. (2002) Heavy Metal Removal by Novel CBD-EC20 Sorbents Immobilized on Cellulose. Biomacromolecules. [Online] 3 (3), 462–465.

5. Chaturvedi, R. & Archana, G. (2014) Cytosolic expression of synthetic phytochelatin and bacterial metallothionein genes in Deinococcus radiodurans R1 for enhanced tolerance and bioaccumulation of cadmium. Biometals : an international journal on the role of metal ions in biology, biochemistry, and medicine. 27 (3), 471–482.

6. Biondo, R., da Silva, F.A., Vicente, E.J., Souza Sarkis, J.E., et al. (2012) Synthetic phytochelatin surface display in Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34 for enhanced metals bioremediation. Environmental science & technology. 46 (15), 8325–8332.

7. Bontidean, I., Ahlqvist, J., Mulchandani, A., Chen, W., et al. (2003) Novel synthetic phytochelatin-based capacitive biosensor for heavy metal ion detection. Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 18 (5-6), 547–553.

8.Pinaud, F., King, D., Moore, H.-P. & Weiss, S. (2004) Bioactivation and cell targeting of semiconductor CdSe/ZnS nanocrystals with phytochelatin-related peptides. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 126 (19), 6115–6123.